Extracts from a longer essay exploring the future of the poster which will be published in Warsaw in June 2016

In 1971 the Swiss graphic designer Josef Müller-Brockmann and the artist Shizuko Yoshikawa published a book surveying the history of the poster. Committed modernists, they concluded their catalogue of past designs with some reflections on the form’s future. They saw flashes of optimism in the foundation of the Warsaw International Poster Biennale in 1966 as well as the city’s Poster Museum two years later, and in the creation of the Deutsches Plakat Museum in Essen in 1971. Here was evidence of the poster’s “great importance as an economic, social, political and cultural means of communication.” Yet, at the same time Müller-Brockmann and Yoshikawa worried about its end:

It cannot be foreseen with certainty whether, or for how long, the poster will have a long-term future. Doubts regarding its prospects are justified when we consider the possible way of life of a post-industrial society, with almost unlimited new technical resources in an environment planned according to human resources. Some practical aids, which scientific and industrial production is placing, or will place, at our disposal in the near future: audiovisual communication by telephone: audiovisual communication with stores providing a survey of good available, automatic order and deliver in house; audiovisual communication with a neutral marketing advisory office; a newspaper delivered by home computer, independently of time, giving all desired marketing information by means of stereoscopic pictures; a home computer connected to a data bank of administrative associations and giving topical information regarding social, and political events …[1]

Reading their words today, it seems clear that, in outlining their vision of a future after the poster, Müller-Brockmann and Yoshikawa foresaw the Internet.

[…]

Such anxiety about the decline of the poster has proven, at least in terms of volume, to be premature. Advertising continues to fill the horizons of our towns and cities; elections and political protests still warrant the production of great waves of visual propaganda; and cinemas, galleries and theatres announce their programmes with graphic posters as they have always done. Occasional moratoriums on billboard advertising issued by cities in an ascetic mood – …– do little to reverse the flow. Moreover, the conventions which first governed the design of the modern posters in the age of Lautrec and Mucha, and, later, Müller-Brockmann too, are still intact today, at least when it comes to the output of professional graphic designers. “The values of a poster are first those of ‘appeal,’ and only second of information” wrote Susan Sontag in 1970: “The rules for giving information are subordinated to the rules which endow a message, any message, with impact: brevity, asymmetrical emphasis, condensation.” Arresting graphic images combined with punchy copy continue to demand our attention today. What has changed, however, is that the means by which these appeals are delivered. Digital billboards, interactive screens and even the phones in our pockets are increasingly the means by which poster messages are mediated. In 2014 The Guardian newspaper announced, for instance, that 2015 would be the year when the spend of advertisers on digital and online promotion in the UK would outstrip than on print buses, cinema, billboards, TV and radio combined.[2] Hollywood movies and upmarket television series are now promoted, for instance, with so called “motion posters” – not a trailer but an animation of elements of the promotional poster which lasts little more than a few seconds.

Letters ripple into life; actors strike a pose; lightning flashes overhead. Commissioned by movie studios and television broadcasters (or created by fans), these poster-format designs are easily posted and reblogged on social media. Many motion posters attempt to combine the wide-screen effects and intimate close-ups which characterise much cinema. Whether this constitutes a definition of the genre yet is too early to say: the motion poster is too new to have established a firm set of conventions (and in fact, like many trends on the Internet, it might turn out to be no more than a short-lived fad). Nevertheless, their desire for life is unmistakable. Not only do these posters come to life in your hand or on your desktop but they also want to escape the flat surface of the screen.

The desire for life in the poster can be traced back to its earliest days, or perhaps more precisely to the first movies at the beginning of the twentieth century. As the German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin wrote in Einbahnstrasse (One-Way Street) in 1930:

Today the most real, the mercantile gaze into the heart of things is the advertisement. It abolishes the space where contemplation moved and all but hits us between the eyes with things as a car, growing into gigantic proportions, careens at us out of a film screen. And just as the film does not present furniture and facades in completed forms for critical inspection, their insistent, jerky nearness alone being sensational, the genuine advertisement hurtles things at us with the tempo of a good film.[3]

Writing in Weimar Germany, Benjamin – who set himself the task of diagnosing modernity – stressed the shock effects of the modern media of film and advertising. In this, lay the modern poster’s disturbing liveliness. Today, new, more coercive forms of poster interaction are emerging. The fantasy of the “personalised” billboard which knows you and your tastes – vividly presented in Steven Spielberg’s movie “Minority Report” (2002) – is drawing closer. In 2012 the UK charity Plan UK created bus advertising which scanned a viewer’s face to select an ad according his or her gender. “Men and boys are denied the choice to view the full content” of the “Because I’m a Girl” campaign “in order to highlight the fact that women and girls across the world are denied choices and opportunities on a daily basis due to poverty and discrimination” explained the charity.[4] Similarly, in its #LookingForYou campaign, Battersea Dogs and Cats Home, an animal charity in London, worked with an advertising agency and technologists in 2015 to combine leaflets with RFID chips with electronic billboards and digital displays at a shopping centre.

Holding a leaflet which he or she had picked up on arrival, a visitor was “followed” on his or her journey by an appealing looking dog which appears on every screen en route. Walk back pass the screen and the dog is still there, waiting for you. Here, the shock identified by Benjamin in Weimar Germany has been replaced by a more subtle – and in this case affective – form of interaction which, of course, raises many ethical questions about consent, and about the way in which data about our identities and movement is stored and used. To date, such attempts to customise advertising remain rare and, in fact, the charities concerned have made much of the technology to draw media attention to their good works. And, as the use of the hashtag in the name of the #LookingForYou project infers, Battersea Dogs and Cats Home wishes to share their work not hide it. Moreover, not all forms of interaction carry overtones of manipulation. The UK based company Novalia, for instance, specialises in the development of paper surfaces which offer interactions based on touch. Conductive inks, and electronics and small speakers hidden in a thin board allow a poster to become an drum kit which can be played. Another poster designs – like its “Sound of Taste” – connects with a smart phone. When the artwork, a flood of rich colours created by illustrator Billie Jean, is stroked, different chords are triggered and played out of the speakers on the phone. Commissioned by a spice retailer, Schwartz, the project aims to connect the senses. Such inventions might be dismissed as gimmicks, but Novalia’s achievement is not just to have produced an experimental prototype but to have worked out how to produce interactive posters in large numbers at relatively low cost.

The potential of this technology is considerable, a fact not lost on Google which worked with Novalia and a creative team from 72andSunny to design an interactive “voting” poster for the streets, bus stations and cafes of San Francisco in 2015 which invited passers-by to decide how money the wealthy business had set aside for non-profit schemes with social benefits in the area should be spent.[5]

The Mediation of the Media

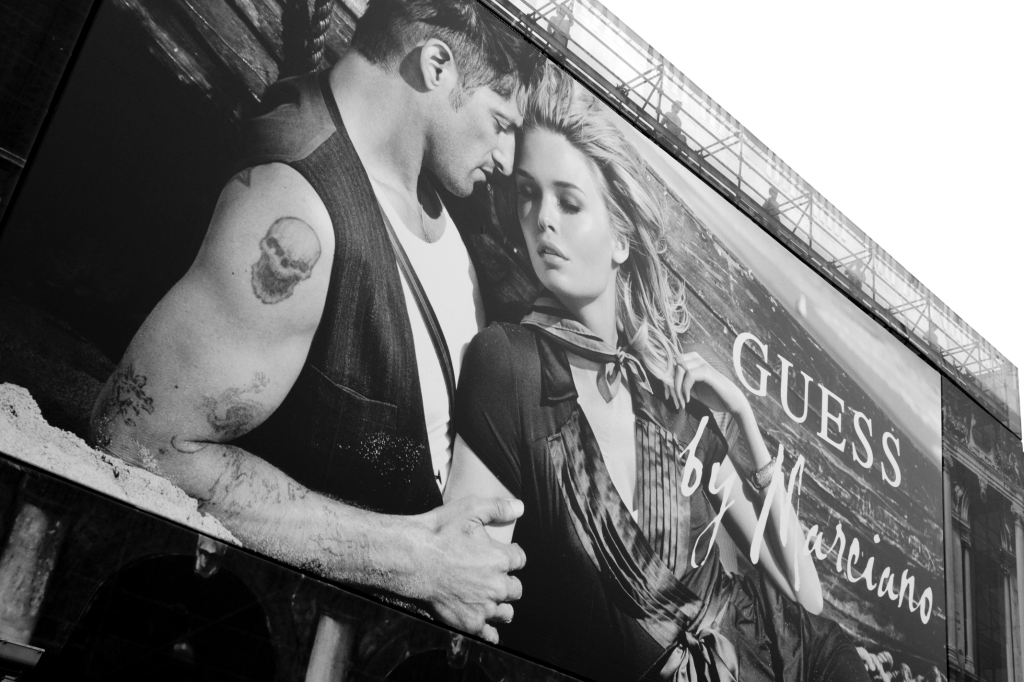

What the appearance of motion posters illustrates is not that the poster has been has killed off by the screen but that poster effects have been subsumed into new media. Far from vanquishing the conventional poster – words and images printed on paper and pasted on the walls of our streets – the screen has consumed it with great appetite. Lively images accompanied by slogans on smart phones contain so many poster-like qualities that they might be best to see them as containers of all the histories of the poster. This is one face of what Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, writing more than a decade ago, called “remediation”. Reflecting on the rapid transformation of the media in the 1990s, they argued that “digital visual media can best be understood through the ways in which they honor, rival, and revise linear-perspective painting, photography, film, television, and print.” Old media are never entirely replaced: they persist but, necessarily, “refashion themselves to answer the challenges of new media”. In other words what is “new about new media comes from the particular ways in which they refashion older media.”[6] Viewed in this way, a digital billboard promoting new fashion is a layered or “seriated” medium in the sense that its graphic components each have their own histories: a sans-serif letterforms might date from the beginning of the nineteenth century; the company’s logo was, perhaps, an invention of the 1960s; the lighting effects might owe much to the studio techniques of Hollywood photographers in the 1930s (who, in turn, had taken lessons from chiaroscuro painters); and so on.

The deep penetration of digital technologies into all aspects of life may well constitute a fundamental transformation of our environment – perhaps even a revolution – but it is one phase in a longer and continual process of what Bolter and Grusin call the mediation of the media: “Each act of mediation depends on other acts of mediation. Media are continually commenting on, reproducing, and replacing each other, and this process is integral to media. Media need each other in order to function as media at all”.[7]

The interdependence of different media both for the generation of meaning and for its distribution is well illustrated by “And Babies?”, a poster created by the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC) in New York in late 1969 to protest against American military involvement in Vietnam.[8]

The poster features words and an image which had already been widely reproduced in the US media before they were combined by the AWC. Eighteen months earlier, in March 1968, a troop of US soldiers had massacred the population of a Vietnamese village, known as My Lai (Song My).[9] The hundreds of people who died in this brutal episode had initially been described by a US army spokesman as a Vietcong unit. The evidence provided by the Army’s own photographer, Ron L. Haeberle, revealed, however, that men and women, old and young, were not only civilians but that they been killed indiscriminately. The images of the dead taken by Haeberle, as well as other shots of peasants recoiling from the menacing GIs, found their way into the American mass media. They were shown on major news broadcasts without commentary, such was their shocking force. CBS also televised an interview with Paul Meadlo, one of the soldier who had participated in the massacre. When asked by TV anchor Mike Wallace whether the soldiers had killed men, women and children, “yes” came the answer. When Wallace pressed again, asking “And Babies?”, Meadlo replied “And Babies.” The next day a full transcript of the interview was published in the New York Times.[10] This was at a time when American attitudes to the war were already changing. And for the anti-war movement, here was brutal evidence of indifference and violence done to the very people the USA was claiming to protect.

Securing official permission to use the photograph and with the endorsement of the Museum of Modern Art, the AWC – an alliance of politically-engaged artists– published “And Babies?”, laying Wallace and Meadlo’s words from the newspaper transcript over the army photographer’s image. Union lithographers donated their services, and paper was obtained without cost. On hearing about the project, the president of the board of trustees of the Museum withdrew the institution’s support. Nevertheless, the AWC went ahead, publishing the poster in an edition of 50,000 copies, which it then distributed “free of charge all over the world” including in the Museum’s lobby. The group issued a press release reflecting on this turn of events:

Practically, the outcome is as planned: an artist-sponsored poster protesting the My-Lai massacre will receive vast distribution. But the Museum’s unprecedented decision to make known, as an institution, its commitment to humanity, has been denied it. Such a lack of resolution casts doubt on the strength of the Museum’s commitment to art itself, and can only be seen as a bitter confirmation of this institution’s decadence and/or impotence.[11]

The group also mounted a “lie-in”, parading the poster in front of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), one of the most compelling anti-war images of the twentieth century, in the Museum’s galleries.[12] In effect, the AWC staged what at the time was being called a “Photo Op”, an event which was organised to attract media attention or, in other words, to be mediated.[13] Perhaps unsurprisingly, the action in front on Guernica was reported in the New York Times.[14] Various art magazines also promised to publish this image on their covers.[15] In the event, it only appeared on the cover of the November 1970 issue of the British art magazine, Studio International. In the same year, the Baden Kunstverein in Karlsruhe, Germany, adopted the poster as the cover of the catalogue accompanying its Kunst und Politik (Art and Politics) exhibition in summer 1970. The cover design was given a kind a gauzy treatment, appearing as if the poster had been shot from a television screen.

Human Billboards

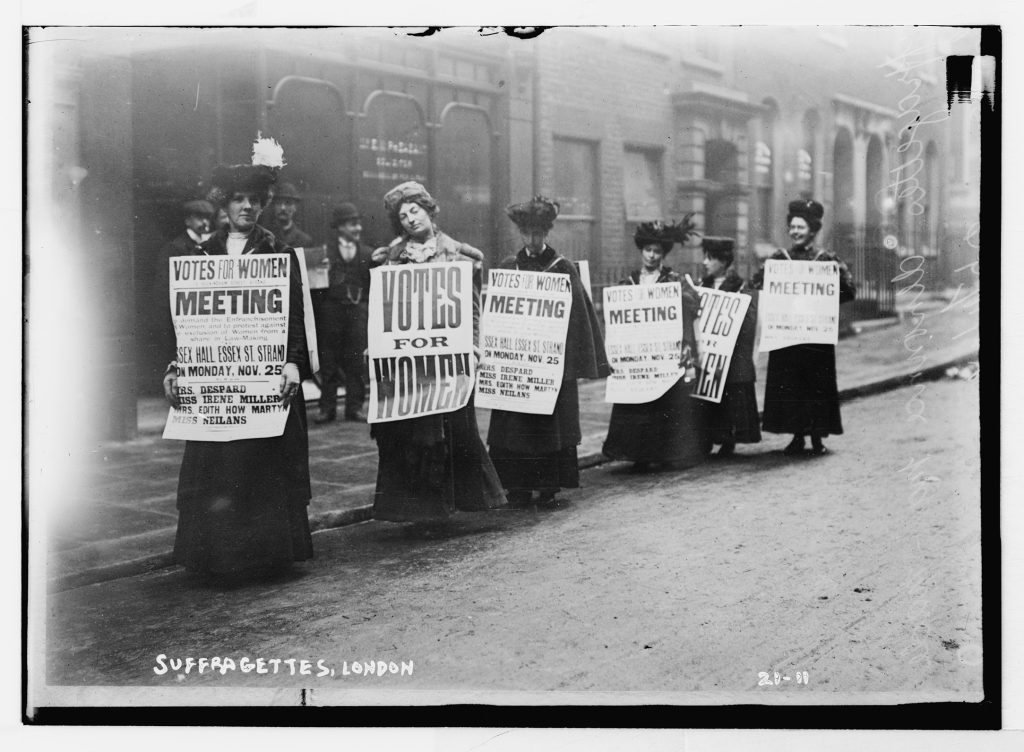

The “And Babies?” poster was fashioned from material which had already undergone various forms of mediation. Moreover, the design – already printed in thousands of copies – was distributed indirectly by being reported in the print media. This particular form of remediation has a long history and a special association with protest. A parade of placards and posters brings a particular advantage to protesters. Inherently photogenic (and, of course, spectacular en masse), vivid posters like “And Babies?” supply their own captions when they appear in press photographs. Moreover, in their mobility, poster parades bring their messages to settings which are already inscribed with meaning. When in 1968 African American sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, went on strike to express their deep frustration with dangerous conditions, as well as workplace racial discrimination, they organised boycotts, sit-ins and marches. Famously, in March three hundred protestors marched from Clayborn Temple, their home base, to City Hall, the site of civic authority in Memphis, as well as their employer. Each carried a placard, printed in the Temple’s print workshop, carrying the slogan “I am a Man.” A assertion of human dignity, these words connected civil rights with campaigns for the abolition of slavery in the eighteenth century.[16]

Such demands for civil rights in the United States in the 1960s; for democracy during the Arab Spring in 2011; or the defence of freedom of speech in the aftermath of the attacks on the offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, in Paris in 2015 had particular poignancy by being printed and carried by ordinary citizens. And their messages were amplified by the way that the posters were borne. When the Memphis sanitation workers marched, they sometimes hung their placards around their necks (much like the Suffragettes in Britain before the First World War).

In this way, they announced “I testify to the injustice which I have experienced”. In his interpretation of the AWC “lie in” at MoMA, Gregory Sholette points to the symmetries between the gestures in Picasso’s aggrieved painting and those the protestors in press photographs – the fist of the fallen soldier echoes the grasp of the protestors on their poster before the canvas.[17] In their expressiveness, gestures of these kinds accentuated the poster’s message.

The murderous assault on the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo and the violence that spiralled out across the city and the country thereafter led to waves of anguished expressions of dismay and anger. The words “Je suis Charlie” were tweeted within minutes. And within an hour, Joachim Roncin, a French artist and journalist, had turned the phrase into a graphic device, employing the block letters of the weekly magazine’s masthead. Expressing solidarity with the victims of the attack and defence of freedom of speech, numerous newspapers and press agencies reproduced Roncin’s design. The day after the attack, Belgian financial daily De Tijd and French newspapers Libération and L’indépendant issued entirely black front pages featuring the “Je suis Charlie” slogan, and similar gestures were made by newspapers in Estonia, the UK and Sweden. Google France added the device to its homepage. But perhaps the most affecting uses of the slogan was by citizens around the world who downloaded a digital file from the Charlie Hebdo website and then carried print-outs in vigils and demonstrations.

Some simply displayed the design on their smart phones. Modest in scale and often adapted by their bearer, these small posters were clasped over the chest or held above the head – effectively giving voice to silent and invariably sombre faces. And the claim on unity in the face of terror acquired full meaning, according to Roncin, by being carried by thousands of people of different genders, races and nations: “It is a purely republican message; one of hope, of solidarity, of peace, of unity that goes beyond Charlie Hebdo. It is a message that says that our fists are raised and we are not afraid. They didn’t just attack an editorial board or Jews or policemen. They attacked the world of free thought.”[18]

The words “Je suis Charlie” resonate with other assertions of human rights: not only “I am a Man” in Memphis but also “I am Spartacus” from the 1960 Hollywood movie; President Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in West Berlin in 1963; and the “I am Michael Brown” banners carried by Black Lives Matter protesters after the shooting of a young black man by the police in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. The frequency of such declarations also forms a ground against which progress itself can be measured, sometimes negatively. This would seem to be one of the points made by the American artist Dread Scott in his 2009 performance “I am not a Man”. Carrying a modified version of the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers’ poster, Scott walked through the streets of Harlem in New York City, historically the setting of some of the most vital forms of black culture in the United States (aka the Harlem Renaissance). In a tie and jacket, Scott looked like a figure from another time, perhaps one of the dignified protestors of the Civil Rights movement fifty years earlier. Most of the documentary photographs recording Scott’s performance seem to capture the indifference of the people around him. And when he stumbles and his trousers fall down, Scott emphasises the pathos of the protestor who calls for acknowledgement of his or her humanity. In the light of continued disadvantage and violence still experienced by African-Americans, Scott’s work can be understood as a commentary on civil rights after decades of activism.

The most provocative version of the human billboard in recent years has been created by Femen, the feminist group which emerged in the Ukraine in 2008 and now has loosely-affiliated branches across Europe, as well as North and South America. Objecting to domestic violence, prostitution, the corruption of female sexuality by pornography, and other forms of misogyny, Femen’s members write slogans across their bare breasts and then engage in acts of civil disobedience, often targeting politicians and religious leaders.

They create what they call “body-posters” through which the “truth [is] delivered by the body by means of nudity and meanings inscribed on it”. Here the correct gesture or body stance is vital: Femen’s organisers train novices how to stand when protesting – feet apart and firmly rooted; with an aggressive demeanour and unsmiling. With one or more breasts exposed, Femen’s activists invoke historical figures of revolution and resistance including, most obviously Eugène Delacroix’s canvas “Liberty Leading the People” (1830), and, from their own homeland, the sword-wielding “Motherland” monument overlooking the river Dnieper in Kiev (completed 1981).

The dramatic and spectacular nature of the events which its activists create, as well as their sex appeal ensures that images of Femen’s actions circulate on the internet and in print and broadcast media. Easily dismissed as stunts, the risks which they and their associates have taken are real. In March 2013, Amina Tyler, a young woman from Tunisia, aligned herself with Femen by posting pictures of herself on Facebook. In one, she had written “My Body is My Own and Not the Source of Anyone’s Honour”, a reference to the meaning attached to the veil in conservative Muslim societies. The response was quick and extreme: she was subjected to death threats, assaulted and arrested.[19] Muslim clerics denounced her actions. Adel Almi, head of the national Commission for the Protection of Virtue and Prevention of Vice claimed that Tyler’s actions “could bring about an epidemic. It could be contagious and give idea [sic] to other women.”[20] Criticism of Femen’s activities does not just come from their enemies: some feminists have objected too. After attacking the sex industry in Eastern Europe, “they started to ‘recruit’ young Muslim women in France”, writes Agata Pyzik, “… conflating, stereotypically, Islam and patriarchy/misogyny. But in doing so, they were not only racist, they neglected the meaning of years of struggle that are behind defending the rights of women from different than European/white background.”[21]

Femen’s actions are undergirded by a utopian belief in universal freedom which overrides – or, as their statement below suggests, prefigures – all cultural and historical distinctions:

In the beginning was the body, the sensation the woman has of her own body, the joy of lightness and freedom. Then came injustice, so harsh that it is felt with the body; injustice deprives the body of its mobility, paralyses its movements, and soon you are hostage to that injustice. Then you push your body into battle against injustice, mobilizing each cell for the war against the world of patriarchy and humiliation.[22]

In making themselves human posters, Femen activists also become targets in actions which they know will provoke a response, even violence. Hijacking meetings and ceremonies organised by the Roman Catholic church, the far right or Muslim groups, Femen’s activists are often dragged off-stage and away from the cameras: sometimes they are beaten in the act. In protesting against violence against women, they induce it. It seems that nudity – carrying association with sexuality and vulnerability – amplifies this effect.

In other circumstances, opposition carries mortal risk. Here, the anonymity afforded by the Internet sometimes provides security. The wave of protest that spreads across the Arab World since 2010 has stimulated the production of what is sometimes called “electronic posters”, i.e., designs which can be downloaded and printed by anyone with access to a domestic printer.[23] This has been the output of Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh (The Syrian People Know the Way), a collective of 15 anonymous artists, formed in 2011 to express support for the Arab Spring protests in Tunisia and Egypt. Established by an art student from Damascus and a calligrapher from Meah, near Hama, the group were joined by Syrians inside and outside the country, and turned their attention to the regime at home. Posted on Flickr and Facebook, their designs – signed by the collective – were carried in demonstrations by university students, civil society activists, and ordinary Syrians who demanded democratic freedoms and an end to the Baathist regime of Bashar al-Assad. Counter-propaganda against the state-controlled media at the time they were made, Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh’s designs often referred to prohibited and, as such, highly combustible, themes.[24] One “electronic poster” carrying the words, “It will not happen again”, features an image of the waterwheel at Hama, the site of a notorious massacre of 25,000 civilians in 1982. Under Bashar al-Assad public discussion of this event was strictly suppressed. In the foreground, a child – rendered like a stencil – seems to be writing on a wall. This is a reference to the events of March 2011 when children graffitied the popular revolutionary chants they had seen on satellite television – “The people want to topple the regime”, “Your turn is coming, Doctor” and “Leave” – on the walls of a school in Deraa were arrested and tortured. Public anger at their treatment was one of the triggers of anti-Assad protests. In another electronic poster, a woman covers her face with a veil or possibly a chequered keffiyeh associated with Palestinian nationalism.

She is framed by the words “I’m going out to demonstrate” in elegant Arabic calligraphy. As Robyn Cresswell notes, the Arabic verb for “to demonstrate,” atazahar, suggests the process of “appearing” or “becoming visible”.[25] Here, the possibility of private identity and public protest – which characterises Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh’s actions – is, itself, the theme of one of its designs. The contrast with Femen’s “body posters” could not be greater.

[—]

Controversies

Protestors are not the only groups which attempt to amplify their poster messages by thumbing a ride in the press or on social media. Lacking the resources to mount expensive print advertising campaigns, charities and other interest groups often court controversy by commissioning publicity which tests public opinion and sometimes contravene the codes which limit advertising in many countries. In this way, a poster can become a news story in its own right. Today, it often seems that sex or images of children are the most effective vehicles for controversy. In 2010 a French campaign commissioned by Droits des Non Fumeurs (The Rights of Non Smokers / DNF) from the BDDP et fils agency set out to capture the attention of the young, who appear to be largely unmoved by warnings of the deadly effects of smoking-related disease. Instead, the director of DNF argued that it was necessary to tap the sexual desires and dislike of authority of teenagers in its press and poster campaign. Featuring the slogan “To Smoke is to be Enslaved”, the campaign images presented the act of young people smoking as if compelled to perform an act of fellatio on an older besuited man. If the clarity of the message was doubtful, the media effects of the image were not. The French press immediately called on public figures to give an opinion – libertarians attacked the publicity’s censorious tone; champions of family values identified paedophilia in the images; and the Minister of Health judged the campaign to be inappropriate precisely because it set out to shock. Evidently, DNF had a “succès de scandale” on its hands, ensuring that its publicity was publicised.

Sexuality also featured in the public discussion of one of the most controversial commercials in the UK in recent years. A series of weight-loss advertisements were placed on billboards and on public transport in spring 2015 featuring a slim and tanned model in a bikini with the question “Are you Beach Body Ready?” The company behind the advertisement, Protein World, produce and market food supplements and meal replacements. The ad immediately drew a critical response, often in ways that combined both a direct engagement with the poster in situ and the rapid, centrifugal effects of social media. Angry passers-by answered the ad’s question personally and directly with marker pens and stickers: one transformed it into “Everyone is Beach Body Ready!”; another replied with “None of Your F*cking Business”.

And, in a witty gesture, two young women, Tara Costello and Fiona Longmuir, were photographed in their own bikinis standing by the ad on London’s tube system. Both feminist bloggers, they captioned this image with their own Q and A (“How to get a beach body: Take your body to a beach”) and then posted their body positive message on social media. These first angry responses spiralled quickly into something like a campaign against ”body shaming”. Protesters gathered on a cold day in London’s Hyde Park, many in swimwear with the slogan “Beach Body Ready” written on their skin. This media-friendly event made the broadcast news that evening. An on-line petition calling for the ad to be banned attracted more than 70,000 signatures. And the advertising Standards Authority (ASA), a regulatory body received 378 complaints largely claiming that the image of the model and the headline had toxic effects on individual well being and confidence.

In the face of such widely reported criticism, the response of Protein World was highly combative, with the company’s representatives taking every opportunity to defend the ad. “Are you Beach Body Ready?”, they argued, was an invitation to viewers to consider if they were in the shape they wanted to be. The company’s head of global marketing Richard Staveley even revealed the company received a bomb threat but said nevertheless that it had been “a brilliant campaign for us”.[26] What would seem to be clear evidence of this fact was that sales of their slimming product increased during this media skirmish. Much to the disappointment of the protestors, the controversial campaign was also cleared by the ASA: “We considered the claim “Are you beach body ready?” prompted readers to think about whether they were in the shape they wanted to be for the summer” declared the UK ad watchdog, “and we did not consider the accompanying image implied a different body shape to that shown was not good enough or was inferior.”[27] Protein World then shifted its attention to the slimming market in the USA, launching their campaign there by placing the same “Are you Beach Body Ready?” ad on a massive billboard in Times Square in New York. Although the public response proved to be more ambivalent , the American press had been primed, with journalists asking passers-by live on breakfast TV “Are you upset by an ad which caused so much offence in the UK?” An ad had become news, again.

Concentration or dissipation?

The remediation of posters in the press and other news media often focuses attention on the message which the poster has been created to deliver. Not all acts of remediation can be understood as the concentration or amplification of information. Some seem to produce the reverse effect; one of deferral and even dissipation. The afterlives of the AWC’s “And Babies?” poster illustrates this point well. In 1970, Gloria Steinem, the prominent feminist activist, added the words “The Masculine Mystique” to the poster, a play on the title of Betty Frieden’s 1965 book about the ways in which the horizons of women living in the USA were contained by the myths of femininity.[28] In Steinem’s reworking, the murder of the villagers from My Lai was an extension of the values which American society drilled into its sons. Speaking at a US Senate hearing on equal rights in May 1970, Steinem said:

… it seems to me that much of the trouble in this country has to do with the “masculine mystique”; with the myth that masculinity somehow depends on the subjugation of other people. It is a bipartisan problem; both our past and current Presidents seem to be victims of this myth, and to behave accordingly. … Perhaps women elected leaders—and there will be many of them—will not be so likely to dominate black people or yellow people or men; anybody who looks different from us. After all, we won’t have our masculinity to prove.[29]

A few months later Steinem carried her reworked version of the poster along Fifth Avenue in New York during a march of 20,000 women in support of the Women’s Strike for Equality. Reframed by feminism, the “And Babies?” had became an indictment of American machismo.

Other acts of remediation of the AWC poster deferred the original message yet further In 1982 East German designer Jürgen Haufe designed a poster for the Dresden State Theatre production of Heinar Kippart’s play, “Bruder Eichmann”, an adaptation of Hannah Arendt’s study of the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961.[30] SS officer Eichmann, an official of the Third Reich, had been responsible for the administration of the deportation of Jews to the Third Reich’s extermination camps. Haufe too created an adaptation, this time of the AWC poster. Roughly erasing the original lettering of the poster, Haufe combined the image the bodies of the dead with another of the keyboard of a typewriter. Here was a sharp indictment of Eichmann’s claims to have been an ordinary and God-fearing bureaucrat innocently caught up in events. For those who recognised the crime at My Lai, Haufe’s design connected the violence of US actions in Vietnam with the Holocaust: for those who did not, the poster produced a more general message about man’s inhumanity. Much is lost and gained in such acts of remediation. In this case, the identities and histories of the dead (and those who killed them) were overwritten by a universal message. […]

The Poor Poster

If remediation undermines the hold of authors on their images, it would seem axiomatic that it infers their spread. In an influential 2009 essay, film maker and writer Hito Steyerl gave a name to describe the order of image which travels fastest and furthest, “the poor image”:

The poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.[31]

In her essay, Steyerl’s primary concern is to understand the circulation of film in an era which is characterised by the rampant privatisation of the media and the collapse of non-commercial infrastructure for making and distributing films. Deterioration may well be understood as the noisy, low resolution of much Internet imagery, but it also can be thought of as the loss of information about who or what is being represented in an image. One only has to look at television news reports which increasingly feature camera phone footage recorded by ordinary citizens of extraordinary events. Shaky and compelling clips of rioting, natural disasters, the activities of rogue police offers, and, of course, images of billboards being destroyed by angry crowds, are often accompanied by the phrase “we have been unable to independently verify this footage” (and there are many examples of news outlets broadcasting material which has been misinterpreted or even manipulated[32]). The compelling and spectacular quality of low-fi, up-close images often overrides any uncertainty about their status as documents. For Steyerl, the rise of the poor image should not, however, be lamented. The circulation and production of poor images based on cellphone cameras, home computers, and unconventional forms of distribution may yet have democratizing effects: “Its optical connections—collective editing, file sharing, or grassroots distribution circuits—reveal erratic and coincidental links between producers everywhere, which simultaneously constitute dispersed audiences.”[33]

What insights might be gained from Hito Steyerl’s essay for considering the poster, especially now that it is increasingly being delivered on digital screens provided by a small number of specialist companies offering advertising spaces (surely the setting of “rich posters”)? Are we witnessing the concomitant rise of the “poor poster” in the twenty-first century and if so where? Perhaps we should look to the home-made banners and placards carried in demonstrations in Tahir Square in Cairo in 2011, in the Maidan protests in Kiev or in Paris in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo murders. Unlike their home-made predecessors in other historic moments, these graphic signs were broadcast around the world almost instantly and without restraint (a lesson perhaps learned reluctantly by President Erdoǧan in Turkey when he attempted, unsuccessfully, to block Twitter in the country[34]). Or perhaps the poor poster takes the form of the ephemeral but highly popular Internet memes which slip between different social media platforms to deliver bitterly sardonic messages (or completely inane ones, for that matter). Moreover, for a some period, the criteria for judging a poster – described above as “the rules for … impact: brevity, asymmetrical emphasis, condensation” – by Sontag have been undergoing a change. Some posters were described as “icons” precisely because they appeared to condense a moment or a condition into a single image and thereafter come to seem like its essence. […] Perhaps this process is an inevitable effect of remediation but in the moment of the “poor poster” other possibilities exist too. Writing of the wide distribution of the technology of image-production and distribution as well as the difficulties of what is sometimes called “image management”, activist and architect Eyal Weizman has described the increasingly multitudinous ways in which events are recorded: “We can no longer rely on what is captured in single images,” he writes, “but rather on what we call ‘image complexes’: a time-space relation between dozens, sometimes hundreds of images or videos which were generated around incidents from multiple perspectives including ground, air and outer space.”[35] Weizman’s point might be illustrated well by a demonstration or an occupation in which police, protesters, professional journalists and independent reporters all carry cameras to capture each others’ actions. Lenses faces lenses. Cameras attached to helicopters and drones observe from above, whilst CCTV networks hold a steady gaze. Attempts to record what might be called the “image complexes” of recent conflicts of this kind include the Occupy Wall Street Archive at http://www.archive.org, a collection of more than 7,500 images, almost 1,250 movies, 339 audio files and 71 texts (at time of writing). It is, in effect, a massive digital archive of the signs, voices, actions and views which made up what might be called “time-space relations“ of Occupy when it filled the business district of Manhattan in 2011. Much of this material has been uploaded by activists to social media sites like flickr, or originates with news media outlets. (We still await the photos and CCTV footage recorded by the authorities and the neighboring businesses). Other recent cataloguing operations include the rapid formation of the Maidan Museum in Kiev to collect not only the artefacts which were created as part of the occupation of the Maidan Square by anti-Yukovich protesters and then its defence during the bloody fighting which broke out in 2014 but also the accounts of the participants.[36] So sharp was their sense of the need to record this historic event, that the future museum’s curators saved the smoke-damaged banners and placards from the Yolka – a tall Christmas tree-shaped structure which had been a temporary gallery of home-made signs – whilst armed militia still occupied Kiev city centre.

Viewed as two poles – the “poor poster”, made non-professional designers that hitches a ride in the mainstream press or spins though the internet, and the “rich poster” created by professional creatives and delivered by digital screens owned by specialist advertising companies who have secured lucrative deals with city authorities – are two very different poster futures, yet they are both likely to persist. Moreover, they both raise questions of public space, whether online or in the streets around us. What rights do citizens have to express their views in public? And what right does society have to exclude irrational or unreasonable views from being posted on walls or on websites? What kind of controls ought to be in place to stave off the domination of our environment by advertising?

[1] Josef Müller-Brockmann and Shizuko Yoshikawa, History of the Poster (Zurich, 1971), 239.

[2] See http://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/dec/01/gadget-obsessed-uk-top-digital-advertising-spend – accessed 23/03/16

[3] Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott (London, 1979) 89.

[4] See http://www.plan-uk.org/news/news-and-features/only-girls-allowed-futuristic-advert/ – accessed 23/03/16

[5] See https://www.72andsunny.com/work/google/google-impact-challenge-bay-area – accessed 23/03/16

[6] Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation. Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA, 1999) 15.

[7] Bolter and Grusin, Remediation, 56.

[8] On this episode see Francis Frascina, Art, Politics and Dissent. Aspects of the Art Left in Sixties America (Manchester, 1999) 160-207.

[9] See William Thomas Allison, My Lai: An American Atrocity in the Vietnam War (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2012).

[10] “Transcript of Interview of Vietnam War Veteran on His Role in Alleged Massacre of Civilians at Songmy”, New York Times (25 November 1969) 28.

[11] Cited in Lucy Lippard, ‘The Art Worker’s Coalition: Not a History’ in Studio International (November 1970) 15.

[12] See Francis Frascina, Art, Politics and Dissent: Aspects of the Art Left in Sixties America (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999) 160-208

[13] Evidently the practice predates the term. According to Kiku Adatto it was coined to describe and disparage Nixon’s attempt to garner media attention by appearing with TV star Jackie Gleason on a Florida golf course during the 1968 Presidential Election campaign. See Adatto, Picture Perfect: Life in the Age of the Photo Op (Princeton, NJ, 2008) 10.

[14] Grace Glueck, ‘Yanking The Rug From Under’ in New York Times (25 January 1970).

[15] See Michael Israel, Kill for Peace: American Artists Against the Vietnam War (Austin, 2013) 135.

[16] See Mary Guyatt, “The Wedgwood Slave Medallion. Values in Eighteenth-century Design” in Journal of Design History, v. 13, n. 2, (2000): 93-105.

[17] Gregory Sholette xxx

[18] Joachim Roncin cited in “Qui se cache derrière le slogan ‘Je suis Charlie’?” (22 January 2015) at www.lesinrocks.com/ accessed 23/03/16

[19] ‘Tunisian activist who posted topless photos is arrested after new protest’ The Guardian (20 May 2013) at www.theguardian.com/world/2013/may/20/tunisian-activist-amina-tyler-charged-protest – accessed 23/03/16

[20] Cited by Laura J. Shepherd, Gender Matters in Global Politics: A Feminist Introduction to International Relations (London: 2014) 301.

[21] Agata Pyzik, Poor but Sexy. Culture Clashes in Europe East and West (London, 2014) 139.

[22] Cited in Femen and Galia Ackerman, Femen (London, 2014) vii

[23] See Liz McQuiston, Visual Impact. Creative Dissent in the 21st Century (London, 2015).

[24] Malu Halasa, Zaher Omareen and Nawara Mahfoud, eds., Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline (London, 2014).

[25] Robyn Creswell, “Syria’s Lost Spring” in New York Review of Books (February 2015) www.nybooks.com/daily/2015/02/16/syria-lost-spring/ accessed 24/03/16.

[26] Staveley cited by Siobhan Fenton in “’Beach body ready’ posters in New York spark counter-campaign” at www.independent.co.uk/ (4 July 2015) – accessed 23/03/16

[27] ASA adjudication (1 July 2015) here: https://www.asa.org.uk/Rulings/Adjudications/2015/7/Protein-World-Ltd/SHP_ADJ_300099.aspx#.VvTrkmSLQy4 – accessed 23/03/16

[28] Betty Frieden, The Feminine Mystique (New York, 1965).

[29] Steinem speaking at a US Senate hearing on equal rights in May 1970. SOURCE

[30] Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Study in the Banality of Evil (New York, 1964).

[31] Hito Steyerl, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’ (2009) in The Wretched of the Screen (2014) 32

[32] See, for instance, http://mediashift.org/2014/12/an-epidemic-of-false-video-footage-swamped-big-news-stories-in-2014/ – accessed 21/03/16

[33] Steyerl, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, 43.

[34] See Kevin Rawlinson, “Turkey Blocks Use of Twitter” in The Guardian (21 March 2014) www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/21/turkey-blocks-twitter-prime-minister – accessed 23/03/16

[35] Eyal Weizman, ‘The Image Complex’ in Loose Associations, Oct. 2015

[36] New York Times article TBC