This essay appears in a book that I have edited in conjunction with an exhibition at Muzeum Susch in Switzerland, Edita Schubert. Profusion. The book features excellent essays by Lina Džuverović, Meghan Forbes, Maja Fowkes, Marko Ilić, Klara Kemp-Welch, Leonida Kovač, Marika Kuźmicz, and Bojana Pejić. You can see a short film about the exhibition here and a trailer here. A thoughtful review of the show appeared in The Guardian and another in Frankfurter Allgemeine.

——–

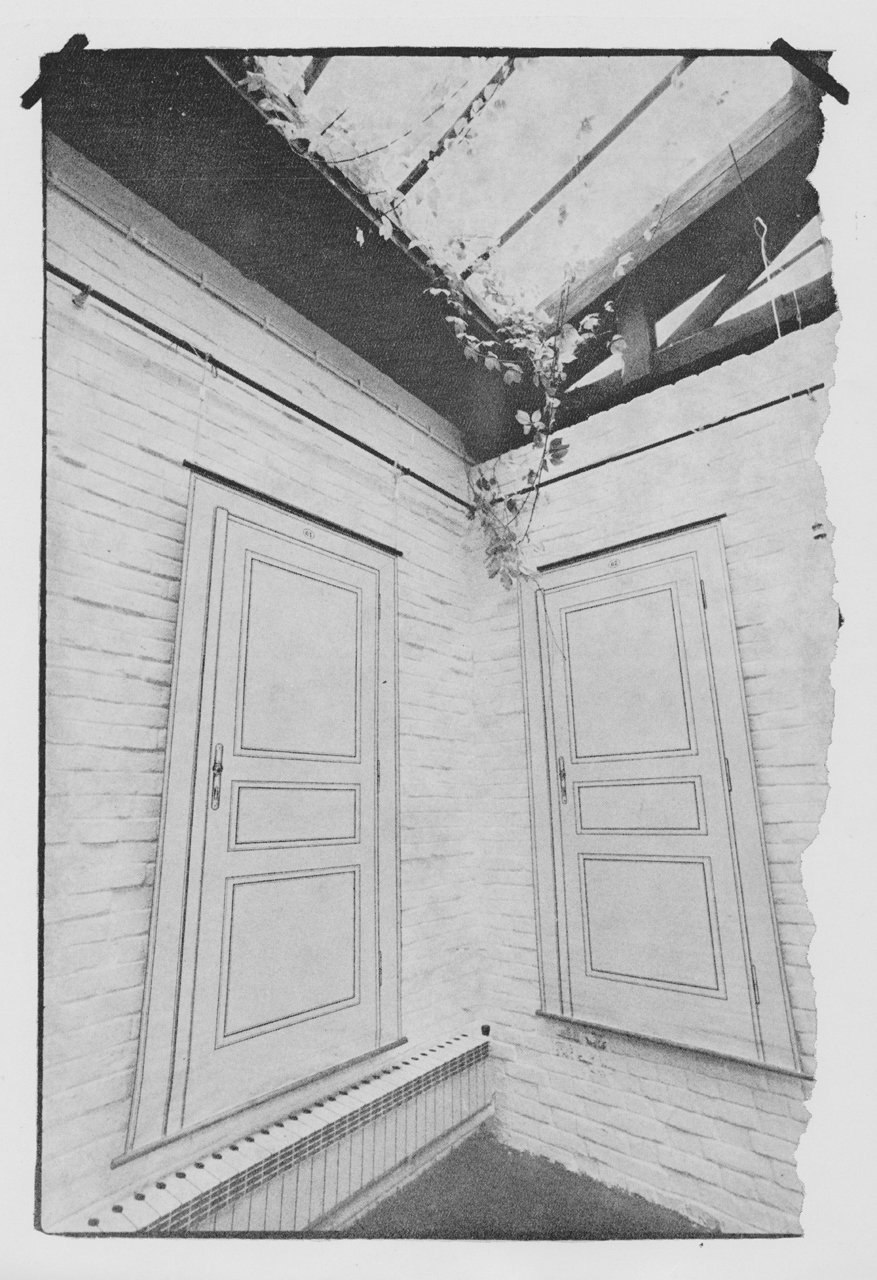

In November 1978, an exhibition of Edita Schubert’s new paintings was held at the Students’ Center Gallery in Zagreb. At least sixteen near-identical canvases titled Doorway (Vrata) signaled an interest in architectural spaces.1 Each took the form of a life-size image of a door. The only distinctions between the paintings were variations in hue (some more gray, others pinkish white or watery blue) and in the number plate on each door, which Schubert traced out in crisp lines of black acrylic paint. Hanging on strings on the whitewashed brick walls of the gallery, these identical doors presented the impression of the hallway of an institution— perhaps an office, hotel, or even a jail. Evidently leading nowhere, they stood in contrast to the equally utilitarian but real door in the gallery, which also bore a number plate. Artist and critic Željko Kipke later described this congregation of doors as a “sealed system” (zakopčani sustav).2

Schubert’s show in the Students’ Center Gallery coincided with the high visibility of New Art Practice (Nova umjetnička praksa), the name given to neo-avant-garde conceptual and performance art in Yugoslavia. Energized by the counterculture of the late 1960s, young artists from across the republics formed a lively and critical field of practice, often drawing on the resources of state-funded student centers like that in Zagreb, or forming their own artist-run spaces.3 Some of these artists are well known today—among them, Sanja Iveković, Marina Abramović, and the OHO Group. Ephemeral and inexpensive art forms like performance, street actions, pamphlets, and posters, as well as the new media technologies of video and audio recording, were employed to issue a challenge to what the influential critic and curator Ješa Denegri called the “‘metaphysics’ of traditional art.”4

In the autumn of 1978, the New Art Practice was garlanded with a major survey exhibition in Zagreb’s Gallery of Contemporary Art, curated by Marijan Susovski.5 Room after room was filled with photographic and textual documents—organized in regular grids—recording dozens of art processes, events, and language games that had been created over the previous decade, usually in public and beyond the conventional setting of the artist’s studio. But success was accompanied by criticism, too, with commentators— some associated with the phenomenon—claiming that the New Art Practice had generated its own clich.s and conventions, despite its iconoclastic rhetoric.6 Might Schubert’s canvases—images of repetition and privacy—have offered one such critique of the New Art Practice?

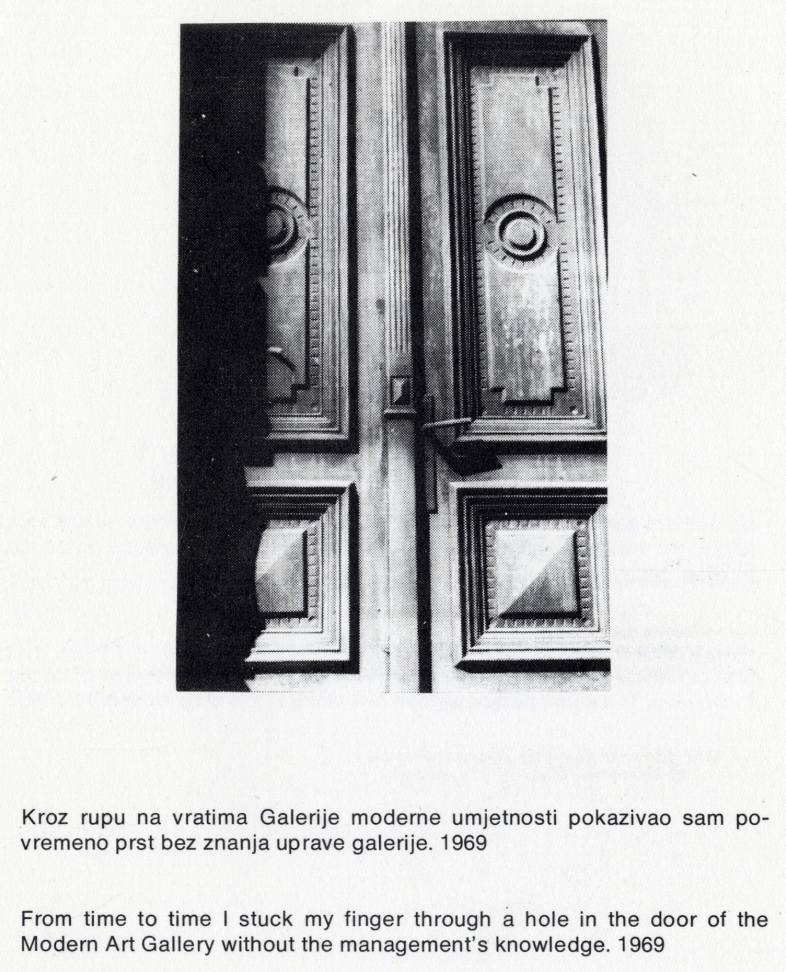

Doors were not new to Yugoslav art in 1978. Indeed, they had appeared in the early days of the New Art Practice, used to ask questions about what art might be, who could be an artist, and where art might be experienced. In Zagreb in 1969, young artists Braco Dimitrijević and Goran Trbuljak had persuaded passerby Tihomir Simčić to press his hand into a lump of clay where a doorknob should have been at the entrance to a tenement building on Ilica Street. Simčić accepted their proposition that he was now an artist and signed the clay sculpture that his grip had made. Soon thereafter, and now working under the name Penzioner Tihomir Simčić (Pensioner Tihomir Simčić), Dimitrijević and Trbuljak discovered an entrance to a tenement on another Zagreb street and persuaded the tenants to let them open a gallery, where five brief shows were held in 1970–71, including a now much mythologized three-hour exhibition of international Conceptual Art curated by Braco Dimitrijević and Nena Baljković-Dimitrijević called At the Moment.7 Their intention to democratize art was also addressed by Goran Trbuljak—critically and wittily—in a document recording an action featuring an image of a solid paneled door, accompanied by a legend (in English and Croatian): Kroz rupu na vratima Galerije moderne umjetnosti pokazivao sam povremeno prst bez znanja uprave galerije. 1969 / From time to time, I stuck my finger through a hole in the door of the Modern Art Gallery without the management’s knowledge. 1969 (left).

The desire for democratization of art was accompanied by attacks on the fetish made of creative genius by the first generation after World War II. In Belgrade, the Student Cultural Center was, for instance, home to a group exhibition in June 1971 with the title Drangularijum (from the Serbo-Croat word drangulija, meaning something like trinket). Artists were invited by the curators Bojana Pejić, Biljana Tomić, and Ješa Denegri to exhibit “found” objects and texts which were dear to them. Drangularijum was, as the curators acknowledged, an exploration of ideas about art set in motion by Duchamp’s concept of the “readymade.” Aesthetic novelty was rejected, declaring that “Drangularijum is a challenge. It is an attempt to introduce uneasiness or provocation in the static atmosphere of Belgrade gallery life.”8 Young Macedonian artist Evgenija Demnievska installed her attic door as a free-standing object in the center of the gallery. The glazed door—with a roller blind—was fixed not to a doorframe but to a vertical pole. It was always open. Reflecting many years later on her attraction to this found object, Demnievska wrote: “The door is a practical object with which I am in contact every day through the door knob. The door allows: opening, closing, entering, passing through, exiting, making of drought, banging, etc. They force me to think about space. I like their appearance. They are functional. Knock—they will open.”9

It was the way in which the door handle reached out that appealed to Demnievska (a gesture that Juhani Pallasmaa has memorably called the “handshake of the building”10). Schubert’s doors eschewed such everyday interactions: there was no doorknob to be grasped, no key to be turned in the lock. No scene could be glimpsed, even through the keyhole. They also rejected the publicness that had motivated Trbuljak and others associated with the New Art Practice. But even when closed, doors like those created by Schubert remain open to the imagination. A room with more than a dozen identical, impassable doorways in a Zagreb gallery was kin to Jorge Luis Borges’s hallucinatory labyrinths or the famous scene in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), in which a tiny gold key refuses to open the doors that flank the hall in which Alice is trapped. Something of this fantastic quality was accentuated by Schubert when she presented her door paintings in the publication accompanying her Students’ Center Gallery exhibition as documents with torn edges and taped-over corners, as if precious records collected in a scrapbook or filed as evidence—though of what, she did not reveal.

Edita Schubert’s Doorway paintings may not have been “readymades” or entrances through which people might pass, but perhaps they were not entirely fictitious either.11 The canvases in Zagreb’s Students’ Center Gallery look much like schematic representations of the door to her studio in the Institute of Anatomy at the Medical Faculty, where she was employed. Her day job—secured soon after leaving the academy—was to produce illustrations for anatomical studies. The position afforded her a modest attic studio at the top of a flight of stairs on the fifth floor of the institute’s neoclassical building in the leafy Šalata district, where she also created her art. Schubert maintained this dual professional existence until her death in 2001. One suspects that the studio was a kind of sanctuary (though, as Sandra Križić Roban wrote in 1999, finding space in which to work—often at scale—was a difficulty faced by Schubert throughout her career12). Represented as a door that could not be opened, the Doorway paintings seemed to signal a concern with privacy rather than publicity.

In the same year as the Doorway canvases, Schubert also produced Staircase (Stubište), perhaps a “life-size” painting of the stairs that led up to her attic studio in the institute. Adapting her own shadowy and evocative photographs that captured the erstwhile grandeur of a building from the last Habsburg years—with high ceilings, polished wood balustrades, and ceramic-tiled floors—she produced another schematic representation. In the translation of the photo to drawing, Schubert stripped out the historical details to produce a universal image of a staircase. When she created the painting, she also arranged for two small timber steps to be made. Placed on the ground immediately below the canvas, they extended the sense of perspectival recession in the flat image. In this gesture, a passage between floors in a building was also turned into one between the material and the immaterial world.

A door and a staircase, but not the attic studio itself: in these images, Schubert seems to have had an interest in thresholds—those in-between zones where inside and outside, and public and private, are met. Who is able to cross a threshold is always a matter of permissions and prohibitions, rituals, and cultural codes. As such, doors, windows, and stairs have the potential to reveal much about the values and axioms of a society, and for that reason, they have drawn the special attention of anthropologists.

Here, the foundation of their thinking is Arnold van Gennep’s Les rites de passage of 1909 (published in English as The Rites of Passage in 1960), a study of the ways in which stages in the life of an individual, changes in status or social relations, and the transfer of power in communities around the world are marked. To be “in-between” is to be on the threshold, or what he called a zone de marge—a marginal or liminal zone. Changes in status or power relations risk unsettling the social order, and, for that reason, the “dangerous” act of crossing a threshold needs to be managed by means of rituals, sometimes involving literal thresholds, though, as van Gennep noted, not always doors:

It will be noted that only the main door is the site of entrance and exit rites, perhaps because it is consecrated by a special rite or because it faces in a favourable direction. The other openings do not have the same quality of a point of transition between the familial world and the external world. Therefore thieves (in civilizations other than our own) prefer to enter otherwise than through the door; corpses are removed by the back door or the window; a pregnant or menstruating woman is allowed to enter and leave through a secondary door only; the cadaver of a sacred animal is brought in only through a window or a hole; and so forth.13

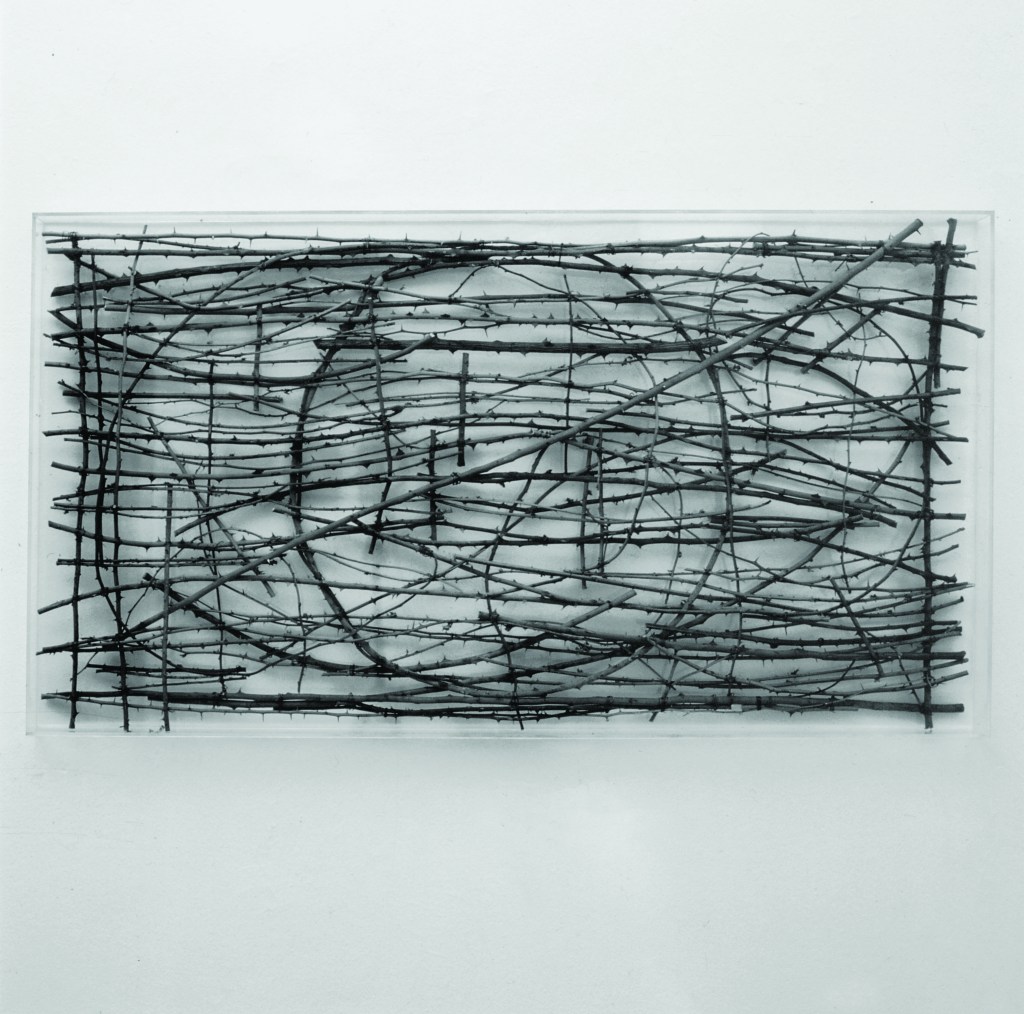

Some thresholds made by Schubert in the late 1970s seem to suggest strongly ritualistic uses—such as her Untitled (Doormat) (Bez naziva [Otirač]) (1979), fashioned by weaving the branches of a wild rose. With its thorns, this briary screen is more of a ritualistic object or even a form of defense than a marker of welcome or the kind of mat with which one might shake off the dust and dirt of the outside world. Edita Schubert’s thorny doormat belongs to a body of works made by twisting, knotting, and weaving untreated natural materials like birch and willow branches into forms that sometimes resemble fences or boundary markers. Other artworks take the form of simple arrangements of twigs and leaves, or collections of natural materials including bone, petals, spices, and ash contained within birch twig circles. When exhibited in the Studio of the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 1980, these works were described by Marijan Susovski as inducing “kinesthetic feelings in the spectator, feelings of ritual acts, operations carried out, associations with the killed, tamed or collected. These are brutal still lifes.” He continued to describe them as “reminders of human presence, of cultivation of nature, and traces of residence … conveying … feelings of tragedy and of nostalgic romance for something unknown, primordial”.14 Indeed, perhaps these objects point to the ancestral beliefs that archaeologists, ethnographers, and folklore scholars of Eastern Europe have traced in enduring rituals, symbols, and apotropaic magic: bones and seeds hidden under the hearths and doorways of medieval homes on the Dalmatian coast for supernatural protection, and ritual and medicinal uses of rose petals, herbs, and many other plants in the same territory today, often absorbed into Roman Catholic rites.15 Socialist modernity had not extinguished these “primitive” beliefs, as numerous Yugoslav ethnographers attested.16 Indeed, Schubert’s ritual objects—described by Susovski as self-consciously “poor” (siromašan)—were created at the high-water mark of Yugoslav ambition, when progress was measured in terms of the length of new highways and the number of new public facilities like universities, hotels, and hospitals. Susovski felt that Schubert’s art—exhibited under the laconic title Radovi / Works in the Studio of the Gallery of Contemporary Art—suggested “ritual acts” conducted elsewhere.

Indeed, she performed one such act in Dubrovnik as part of the city’s Ljetni igre (Summer Festival) in 1981 (left). Responding to the festival’s invitation extended to dancers, theater companies, and performance artists to use the historic fabric and atmosphereof the city’s squares and streets as an inspirational backdrop, Schubert undertook a ritual in a small square beside a fifteenth-century public fountain. A slight figure, Schubert carried seventy-two torches—wooden staves wrapped with rags at one end and sharpened at the other—in bundles inside a rough sack into the square. Tourists dressed in summer T-shirts and shorts watched on. Schubert untied each bundle to lay serried ranks of torches on the flagstones, before creating an irregular crown formation of the staves into which she stepped. This was a threshold of her own making, though perhaps it was a latter-day variant of the protective circle that appears throughout Slavic mythology in the form of peasant dances, fire rituals, and boundary markers. She then reversed the action. All the while, the torches remained unlit.

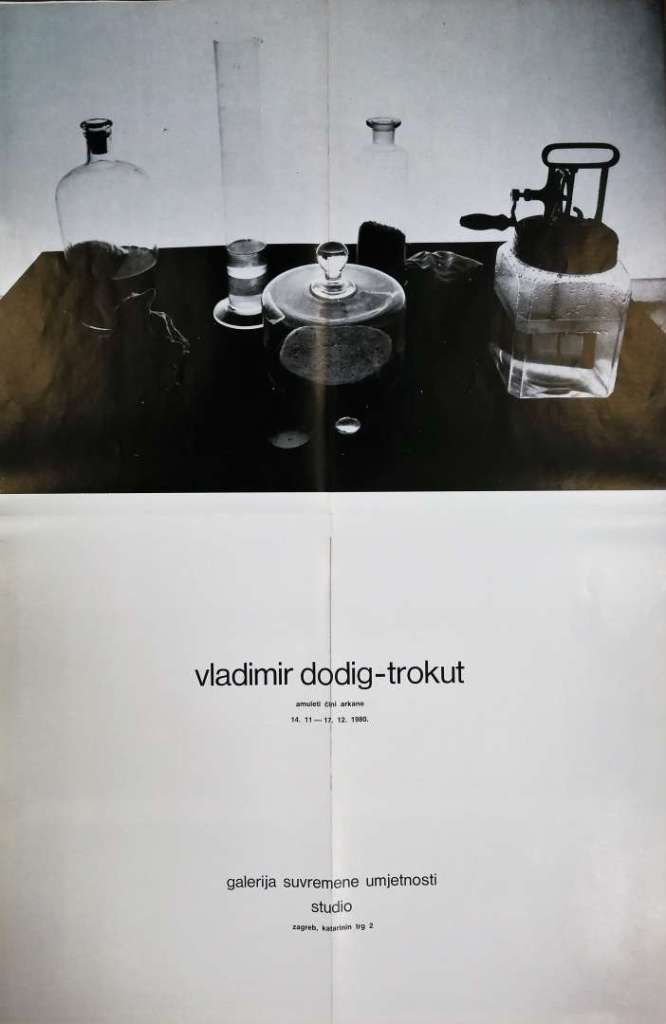

Schubert’s Dubrovnik ritual was by no means an expression of neopagan mysticism or one of the variants of the New Age spiritualism to which a number of other Yugoslav artists were strongly drawn at the time (this, another product of the counterculture). She claimed no magical effects for art, unlike, for instance, the Šempas Family, a rural commune formed in the Slovene countryside in 1971 by members of the OHO Group of artists, for whom “ritual movement, meditation and conversations” could relieve the Earth “of its pollution in a spiritual way”;17 or Vladimir Dodig Trokut, an artist-shaman in the mold of Joseph Beuys, whose 1980 Zagreb exhibition Amulets, Spells and Arcana (Amuleti, čini, arkane) featured discarded objects—some mass-produced—in which he claimed to “recognize atavistic remnants of magical knowledge.”18 In 1980, Trokut’s syncretism infused Duchampian ideas with Dalmatian peasant beliefs.

Edita Schubert’s fascination with thresholds never went away, even though her art pivoted through a number of strikingly different phases in the course of the 1980s and 1990s. It surfaced again in the late 1990s in Endless Tape (Work on the Assembly Line) (Beskonačna traka [Rad na traci]), an expansive band of paper marked with vertical stripes that Schubert ran at eye height over dozens of meters through the interiors of a number of prominent Zagreb galleries, and, outside, on Dubrovnik’s city walls. In the Museum of Contemporary Art in 1995, she arranged for all of the doors in the historic building—in six interconnected rooms—to be removed. Without these interruptions, the Endless Tape produced a surprising effect. According to the art critic Ivica Župan: “With its dynamic winding across the walls of an apartment once inhabited by Croatia’s oldest noble family until 1945, the endlessly running frieze created a strong impression of a labyrinth. It compressed all six rooms into a single, somewhat claustrophobic space, so it’s likely that some visitors felt uncomfortable inside.”19

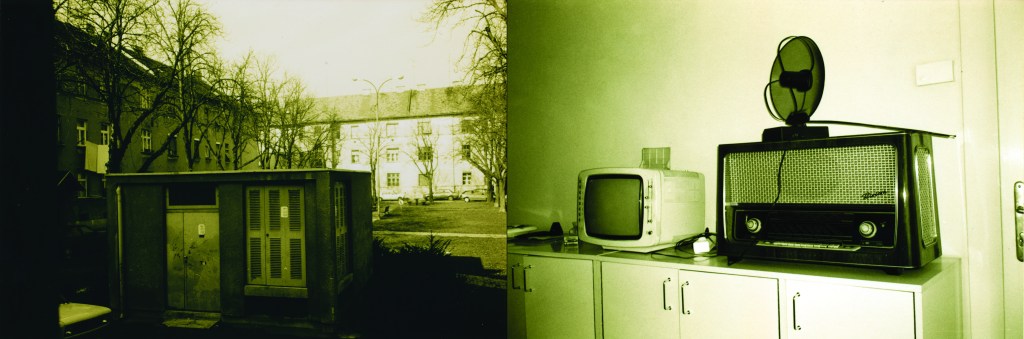

It was a late project called My Apartment (Moj stan) (1999) that brought a new and rather different set of associations of liminality to Schubert’s practice. In March 1999, she arranged for viewing devices to be placed inside the windows of eleven small shops and cafes in the vicinity of Cvjetni trg (Flower Square) in central Zagreb and sent out invitations to individuals to view the work. Small Styrofoam blocks with two viewing lenses and slides were placed at eye level in each window, interrupting the displays of books in one store, cosmetics in another, baby-care products in a third, and so on. The device looked a little like a variant of stereoscope viewers developed in the late nineteenth century which, by exploiting the phenomenon of binocular vision, gave their users the illusion of spatial depth. An individual viewing experience, stereoscopes offered an intimate and safe illusion of distant worlds from the comfort of home. Perhaps this is what Schubert’s viewers expected when they approached, pressing their faces close to the shop and caf. windows—an impression that surely seemed absurd to those passing by. Instead, what they experienced was what might be called ocular dissonance. Rather than seeing twin images cohere, they were presented with an image of the interior of Schubert’s own apartment on the ground floor of Petrova Street in one viewing lens, and with the view from the window of that same apartment into the square outside in the other lens. Populated with parked cars and garbage bins, it was an entirely unremarkable location. Each shop or cafe window hosted a different pair of images, but always of the interior and exterior of her home. With their faces pressed to glass, the viewers were transported from one ordinary setting— the streets around Flower Square—to another: Schubert’s own two-room flat.

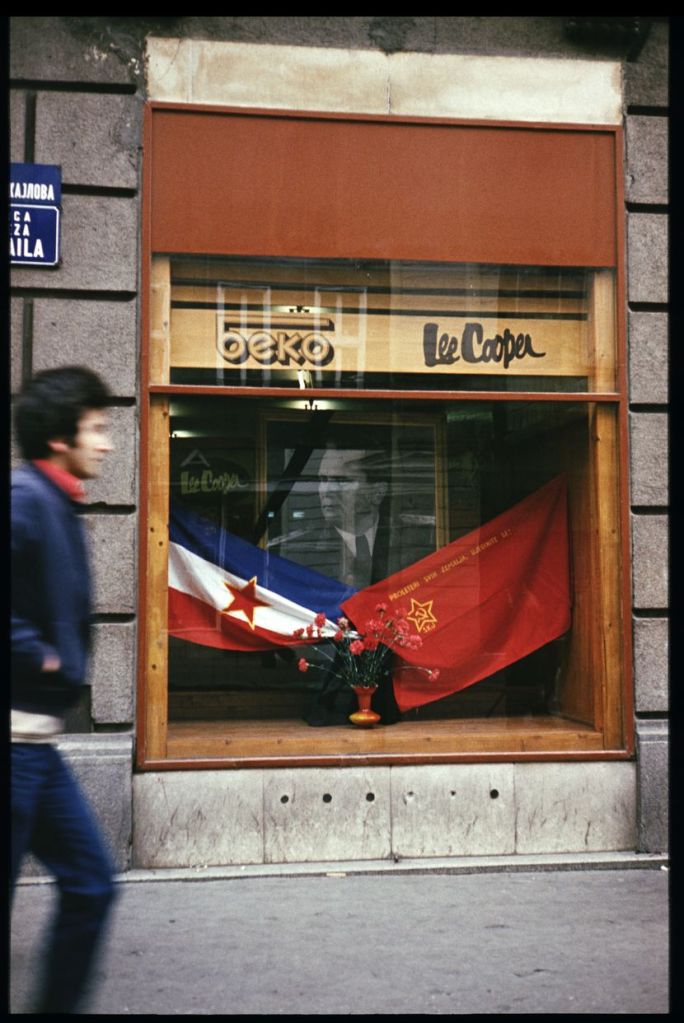

In the Tito era, a number of Yugoslav artists used shop windows and retail districts to comment on the country’s attempt to combine socialism and consumerism. Famously, the first issue of the “anti-magazine” issued by the Gorgona Group in 1961 featured the same image of an empty shop window display repeated—somewhat melancholically—eight times. When Tito died in May 1980, Goranka Matić walked the streets of Belgrade for several days, photographing shop windows displaying photo portraits of the ubiquitous president. Somber portraits and black ribbons shared space with sides of meat and displays of brightly colored clothes, sometimes producing absurd assemblages.20 These memorials seemed to Matić like “a pagan sacrifice to God.”21 But My Apartment was made in another world and time—after Croatian independence and the brutal war that followed. Shop windows— mostly filled with imported goods and glossy publicity—were interrupted by images of Schubert’s ordinary life. Her cramped but tidy Petrova Street apartment—with her art on its walls but also outmoded possessions and traces of her everyday life—introduced notes of banality into the primary setting of consumerism: the shop window. But the effect was hardly a vigorous critique of consumer phantasmagoria. And reviewers seemed to find much more to say about the “real” intimacy of a home than its reification by commercialism. In his review, Župan was struck by the open invitation into her home:

The artist lets us into all these spaces without reserve, hiding nothing, embellishing nothing, while we, curious and voyeuristic like in a peep show, peek into her intimacy. Everything in that apartment is orderly and neatly arranged in a bourgeois sense, and her personal intimacy is partly revealed through the paintings and sculptures—evidently works by various authors—with which she has decorated her living space, while her “social” intimacy is evidenced, for instance, by an old TV set and an even older radio receiver …22

For the first time in a career marked by interest in thresholds, Schubert invited the viewer in.

What are the implications of this fascination with thresholds for Schubert herself? After all, the doors, stairs, and windows featured in her art were parts of her own world. They were not the indifferent non-places to which the category of liminality has often been attached, such as hotels and airports, nor were they the crossroads of fate found in literature. Her studio, her home, and the Zagreb galleries in which she exhibited form significant spaces in her artistic biography. They were formative in the sense that they permitted her to individuate herself as an artist, perhaps even to engage in some kind of self-realization, but they were hardly autobiographical in the conventional sense. Even the photographs of her home in My Apartment offered little sense of narrative or a personal backstory. What psychic or personal thresholds were being crossed by her? One suspects that the appeal of thresholds lay not in the fact that they permitted what Arnold van Gennep called “passage”: rather, it lay in their in-betweenness, their ambiguity. Perhaps this accounts for the disquiet and unease that commentators often sensed in her art, too. Edita Schubert seems to have wanted to hold her viewer at the threshold, not allowing them to cross over or to fully pass through.

- This approximate figure is based on the images in the accompanying catalogue, Edita Schubert, Students’ Center Gallery, Zagreb, October 19 – November 7, 1978 ↩︎

- Željko Kipke, “Kupole i katedrale,” Vijenac 564 (November 2015), http://www.matica.hr/vijenac/ ↩︎

- For a comprehensive history of these institutions and the New Art Practice, see Marko Ilić,

A Slow Burning Fire: The Rise of the New Art Practice in Yugoslavia (Cambridge, MA, 2021). See

also Darko Glavan, Galerija SC – 40 godina, exh. cat. Students’ Center Gallery (Zagreb, 2005). ↩︎ - Ješa Denegri, “Art in the Past Decade,” in The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia 1966–1978,

ed. Marijan Susovski, exh. cat. Gallery of Contemporary Art (Zagreb, 1978), p. 9. ↩︎ - Susovski, The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia 1966–1978. ↩︎

- For an analysis of these criticisms, see Ilić, A Slow Burning Fire, pp. 177–85. ↩︎

- See Ivana Bago, “Something to think about: values and valeurs of visibility in Zagreb from 1961 to 1986,” published on the Parallel Chronologies website, https://tranzit.org/ exhibitionarchive/. ↩︎

- From the accompanying exhibition catalogue (1971), cited in Jelena Vesić, “Drangularijum: Ready-Made Exhibition or Peoples’ Curio Cabinet,” also available on the Parallel Chronologies website, https://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/drangularijum-skc-gallery-belgrade/. ↩︎

- Demnievska in correspondence with Anja Foerschner in Foerschner’s Female Art and Agency in Yugoslavia, 1971–2001 (London, 2024), p. 21. ↩︎

- Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (London, 2012), p. 62. ↩︎

- This observation was made to me by Leonida Kovač. I am grateful to her for this insight, as well as for many other expert observations about Schubert’s oeuvre. ↩︎

- Sandra Križić Roban (1999), cited in Dora Derado Giljanović, “Od slikarske artikulacije do aproprijacije: transgresivna umjetnost Edite Schubert,” Treća 1, no. xxvi (2023), p. 63. ↩︎

- Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage (1909), trans. Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee (Chicago, 1960), p. 25. ↩︎

- Exhibition Edita Schubert: Radovi, Studio of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, May 29 – June 15, 1978, exhibition catalogue with an essay by Marijan Susovski, n.p. ↩︎

- Kelly Reed, “Ritual household deposits and the religious imaginaries of early medieval Dalmatia (Croatia),” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 56 (2019), pp. 1–10; Łukasz Łuczaj, Marija Jug-Dujaković, Katija Dolina, Mirjana Jeričević, and Ivana Vitasović-Kosić, “Ethnobotany of the Ritual Plants of the Adriatic Islands (Croatia) Associated with the Roman-Catholic Ceremonial Year,” Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 93 (2024), pp. 1–16. ↩︎

- See E. A. Hammel et al., eds., Among the People: Native Yugoslav Ethnography; Selected Writings of Milenko S. Filipović, vol. 3 of Papers in Slavic Philology, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI, 1982). ↩︎

- Tomaž Brejc, “The Family at Šempas,” in Susovski, The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia, 1966–1978. ↩︎

- Vladimir Dodig Trokut, Amuleti, čini, arkane, Studio of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, November 14 – December 7, 1980, exhibition catalogue, with an essay by Marijan Susovski, n.p., https://antimuzejportal.wordpress.com. ↩︎

- Ivica Župan, “Edita i četiri friza,” Život umjetnosti 59, no. 1 (1997), p. 123. ↩︎

- Goranka Matić’s photographs were not available until 1995 when the Vreme knjige publishing house in Belgrade issued a collection of them in a book titled Dani bola i ponosa / Days of Pain and Pride. ↩︎

- Goranka Matić, cited in Jelena Pašić, “Drug-ca Fotografkinja” (October 12, 2022), http://www.portalnovosti.com. ↩︎

- Ivica Župan (1999), cited in Giljanović, “Od slikarske artikulacije do aproprijacije …,” pp. 19 and 63. ↩︎