In a dim corner of my room, for longer than my fancy thinks,

A beautiful and silent Sphinx has watched me through the shifting gloom.

— Oscar Wilde, The Sphinx, 1907

Andrzej Klimowski’s career spans more than half a century. In this interview conducted in London in Spring 2025 for the catalogue of a forthcoming exhibition at the G Art Museum in Fujian, he reflects on the different phases of his creative life. He began his career as a poster designer in Poland in the 1970s, crossing from West to East – an unusual direction of travel during the Cold War – before returning in 1981 to the United Kingdom, the country that he’d grown up in, to become an illustrator and author of a remarkable series of graphic novels.

DC: When people talk about your work, they often refer to its dreamlike quality. They see it, but do you? Is this something that you aspire to produce in your work?

AK: It emerges. I certainly recognise it, but I don’t intend to be a dream-image maker. Rather, I am interested in that sort of twilight world between consciousness and the dream – much like David Lynch, who I admire very much – whose films explore the border between the imagined and experience.

I think this interest has a lot to do with a sense of displacement, which I felt early on in life. I was conscious of coming from a family that doesn’t really fully belong to England. My first language was Polish, and my parents were terrible speakers of English. I partly belonged to a faraway land, even when living in England. This was accentuated by the fact that in my early years I lived in a house in London which happened to hold the archives of the Polish underground army from the Second World War– the army to which my dad belonged. And there were many families living there. The four of us lived in an L-shaped room with a kitchen, alongside the others with whom we shared our house. There were Poles, Lithuanians, Greeks too, and even a French family. When visitors called, they rang a doorbell. A long ring or a short ring – like Morse Code – was required to summon the attention of the right person.

I was fascinated with all of this when I was a kid because I witnessed the coming and going of these often very distinguished guys. A General ‘so-and-so’ might visit the archives. And there was an architect that I was really fascinated by, because he had a room full of interesting objects. And when we were slightly older, my sister and I had a kind of adopted auntie. She spoke perfect French and lived in the attic. There was also a very strange guy who was deeply religious and used to make pilgrimages to places like Fatima or Lourdes, bringing back all kinds of rosaries and strange crucifixes. It was a microcosm – a world full of eccentrics.

I also had a godmother who seemed aristocratic, or maybe just quite well off, because her husband ran a brewery before the war in Poland. We used to visit their home. It was full of antiques, maps, sabres on the walls. I just loved the place… And people smoked. I always thought the smoke contained the thoughts of wise men.

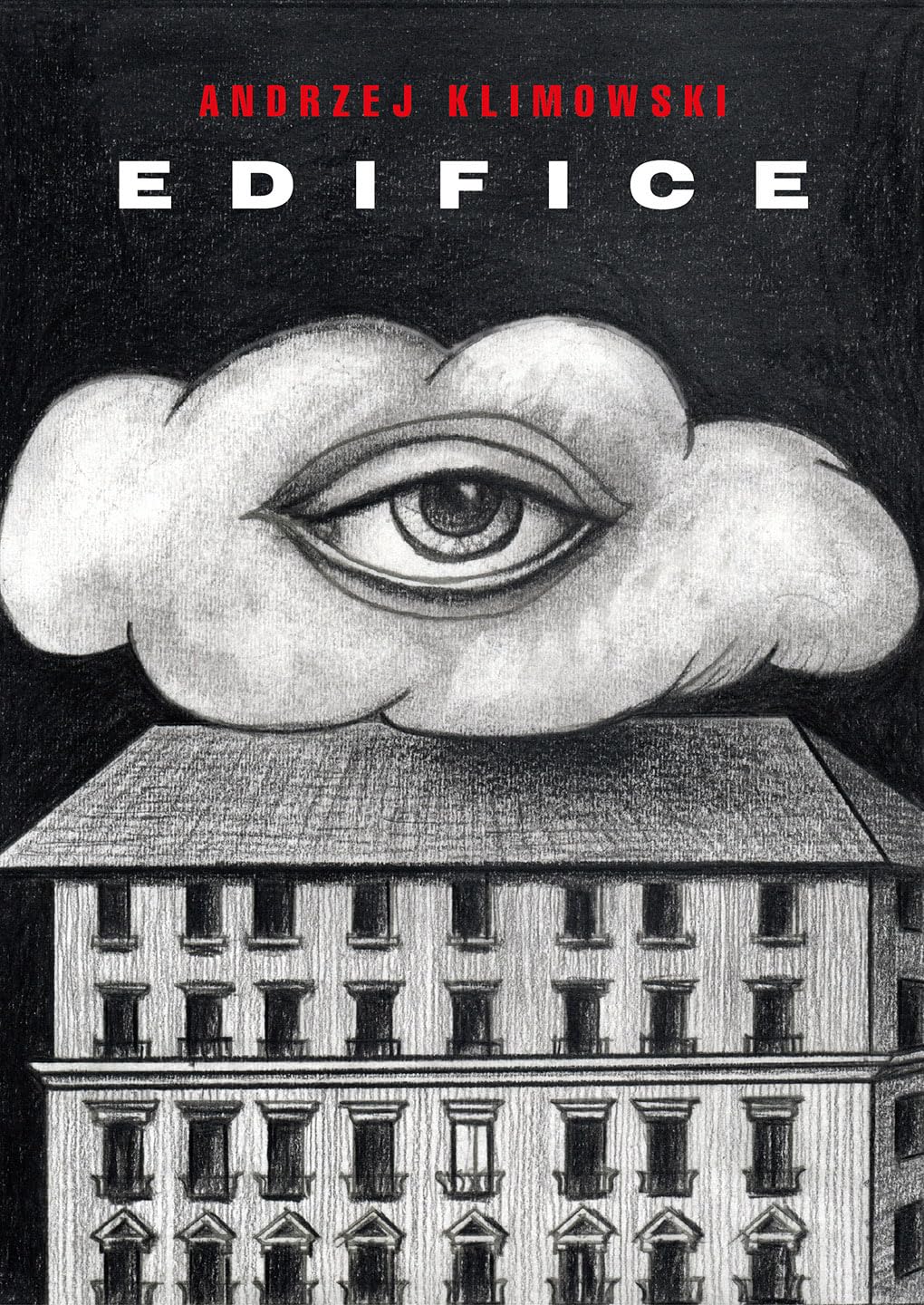

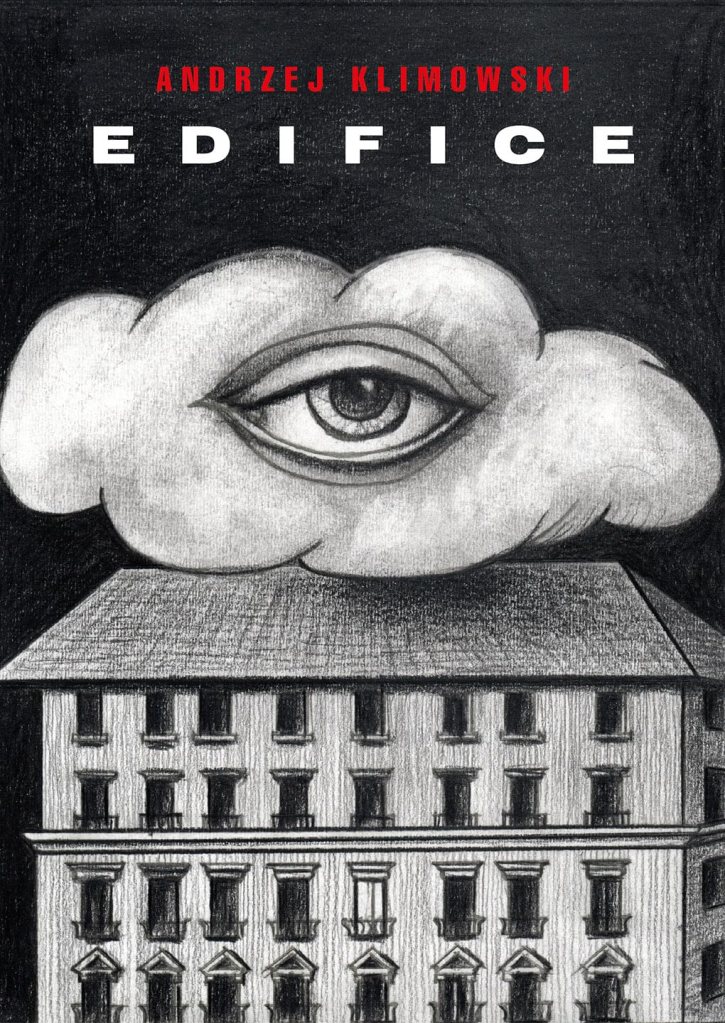

DC: I see traces of that world and those characters from your childhood in your graphic novels like Edifice. It seems not only like a lost world but also a distinctly Central European one too.

AK: When my father was persuaded by his friends to visit communist Poland for the first time, he was tentative, given his war record in the Home Army. Nevertheless, the whole family went by coach. When we were crossing one of the borders, he showed his passport to the guards. I remember that it said he’d been born in Austria – in Kraków [before 1918 when the city had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – DC]. My grandfather had worn the uniform of an Austrian soldier too. Central Europe was a historical place, but it’s also like a worldview or a mentality too…

DC: That makes me think about your attraction to the disturbance to the natural order in Franz Kafka’s stories – like his human insect in The Metamorphosis, or the ‘case studies’ analysed by Sigmund Freud.

AK: Yes, insects appear often. Perhaps this comes back to the place where we lived too, because I was fascinated by the garden. There were black ants everywhere, and also there were an army of red ants. When a plum fell from a tree, the red and black ants would form armies to go into battle over the fruit. I recall a rock garden too, with oddly shaped rocks that are still embedded somewhere in my memory. I think that a lot of our childhood is coded in our memories and still influences us.

DC: Buildings are embedded there too. Where does your fascination with modernist architecture come from?

AK: Yes, I love it. When I was displaying artistic interests and wanted to go to art school, my parents wondered about my future. They asked, ‘Why don’t you study architecture? It’s still artistic.’ At the time, in the late 1960s, there was a show of the Bauhaus school at the Royal Academy in London, which I went to see, and I was really fascinated by it. There was modernist furniture at home too – the architect’s room – and that simplicity, pared-down functional design, and aesthetically beautiful bent-wood attracted me.

So I applied to study architecture at Newcastle University. At that time, I had an interview to study art at Saint Martin’s College of Art in London as well, and they gave me a place there too. My dad didn’t interfere in my decision. He could see I was very happy.

DC: And then you went to Poland in the seventies.

AK: Yes, in 1973.

DC: That was obviously important for shaping your practice.

AK: It was. I graduated from St Martin’s in painting. But I was running the Film Society at the College with my friends. I made the posters for the screenings – often screen prints. And of course, that’s when I discovered Polish cinema. And so, after St Martin’s, I wanted to go to the Łódź Film School in Poland. But I could not get a grant from the British Council to study for the 4 or 5 years it would take. So the Poles said, ‘We’ll give you an official grant.’ But I was from an émigré Polish family: ‘How could I take a grant from the communist authorities?’ I said, ‘No thanks.’

I also went to visit Henryk Tomaszewski, the Polish poster designer, in early 1972, before I left St Martin’s. I showed him my work. He was excited and said, ‘Yes, we’ll take you at the Academy.’

DC: What did studying and then working in Poland give you that you wouldn’t have got elsewhere?

AK: Well, Polish graphic art is actually very visual. Generally, they’re not brilliant typographers, though Roman Cieślewicz was very good. But they’re visually orientated – much like Polish theatre too. The curtain goes up, and you don’t hear any dialogue for quite a while, just tremendous sound and vision. And this visual culture is what excited me.

DC: And what distinguished studying in Warsaw from what you’d experienced in London?

AK: Well, first of all, it was the quality of teaching. And I knew I wanted to be with Henryk Tomaszewski. I liked his work as a poster designer, and I’d heard about his approach to teaching. That was different from London. In Fine Art at Saint Martin’s, you did your own stuff and, if you were lucky, a tutor would come in and say a few words, or slip you a postcard with a painting to look at. But with Tomaszewski, I learned a hell of a lot. For him, the most important thing was clarity. And to develop a distance from your own work. He encouraged you to approach your own images almost as if they’d been done by somebody else, and then judge them objectively. He insisted that we ask: ‘Does it work? Does it fulfil all the functions? Be direct and to the point, and cut out any stuff that’s anecdotal or that doesn’t fit.’ He was tough too, and would set tricky briefs. For instance, ‘Do a poster based on a big nothing and a small nothing in two pictures in a vertical position.’ He was inspired by Stanisław Lec, a poet famous for his aphorisms. And so you had to use your brain.

He’d set those subjects, and then you had to bring in sketches to class – very small sketches, but in proportion. He’d look and say, ‘That doesn’t make any sense,’ or ask, ‘What’s your thinking here?’ And then, if you were lucky, he would settle on one drawing and say, ‘Well, there’s something there. Why don’t you develop it further?’ You did, and then more discussions would follow. When you settled on one design, then you had to do it full poster size – 100 by 70 cm. So my work was tricky because it was collage. Very often I’d work in fragments, montaged together with pins, on an easel. Tomaszewski would say to you, ‘Well, there’s an imbalance there.’ He might even take a pair of scissors to your design and say, ‘Think about it again.’

DC: Your poster work from this time in Poland often features montaged images, sometimes using blow-ups where the half-tone dots of your source material are visible. Was that technique developed in Poland?

AK: No, it started prior to that and can be traced to my fascination with photography and film. At St Martin’s, I spent most of my time in the darkroom or editing film. I discovered the special magic of images suddenly appearing, or, if you juxtapose one’s own made image with a found image, two realities combine and produce something truly unexpected. Posters should be unexpected.

So I was already developing that way of working. Before going to Warsaw, I used to look through the journals in the library in London too – Gebrauchsgrafik and Graphis. There, I discovered the work of Roman Cieślewicz, Jan Lenica, and Wojciech Zamecznik – Polish designers who used collage. In Poland, I carried on doing that, making work in that fashion, and Henryk liked it because it was not like his own work.

DC: So you graduated from the Warsaw Academy and you set about making a career as a designer in Poland?

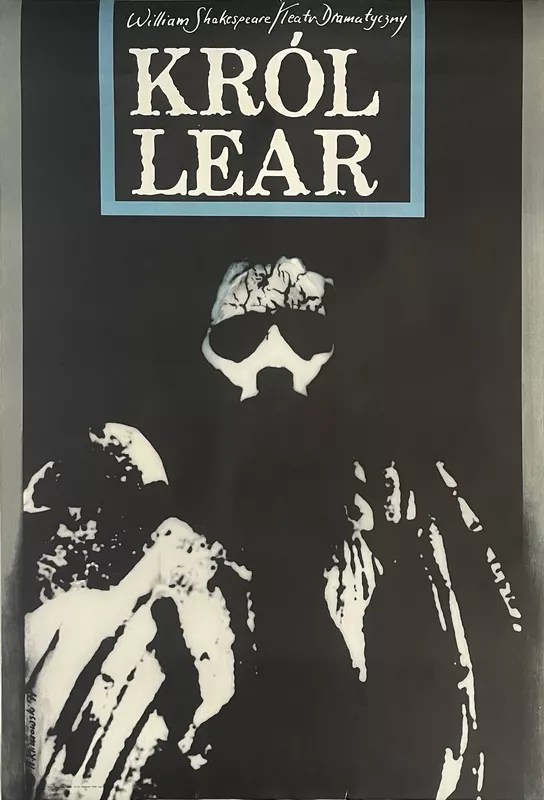

AK: Yes, I was already approaching book publishers when I was there. And, of course, designing film posters was prestigious, and I wanted to be commissioned. But I started my Polish poster career through theatre. I’d heard that there was to be a production of Gombrowicz’s Ivona, Princess of Burgundy, and I loved Gombrowicz’s writings. So I made a full-size design and took it to the theatre. When there was a break in rehearsals, I came out from the wings holding this large poster. And the director, Jerzy Jarocki, said, ‘Wow, that’s great, but we’ve already commissioned someone else. But next season, I am directing King Lear.’ And so I got the next commission.

I did a few other theatre posters, but film commissions still eluded me. To design film posters, you had to be a member of the artists’ union, but to get membership you had to prove that you had been working as a poster designer. It was a Catch-22 situation. But I did have a few theatre posters and book commissions under my belt. When I talked to the Union, they said, ‘Get a letter of recommendation from Tomaszewski,’ which I did and took to the Ministry of Culture. He’d written, ‘It was almost a pleasure teaching Klimowski.’

Even when I got the union membership, I kept on trying to get film poster commissions but to no avail. In the end, an American film was being previewed for the purposes of commissioning the poster, but unfortunately without subtitles. At that time, very few people could speak English. So what could the publisher do? The answer came back… ‘Klimowski’. After that, my career accelerated.

DC: So in a short space of time you were able to produce really an extraordinary range of posters.

AK: Yes. And being a film buff, it was great. But creating my designs was not easy. I could not use the Academy’s darkrooms and other facilities. I had to improvise in my bathroom at home. But improvisation can be a benefit too, in a unexpected ways. Because I could not keep my negatives free of dust and scratches, imperfections became part of the fabric of my work, part of the language that’s remained with me to the present day. I like grids. I like texture. I like film’s imperfection, you know. I find that person more beautiful because they’ve got a scar or a crooked nose than this perfect woman or that handsome man, you know.

DC: What else do you think you brought back from that time in Poland when you returned to London?

AK: I was determined to continue to be an individual, and not to conform with the slick, commercial approach in the UK. I didn’t like graphics in England at all when we arrived back in 1981. I thought that I might teach, because it was a way of maintaining a more artistic, less commercial approach.

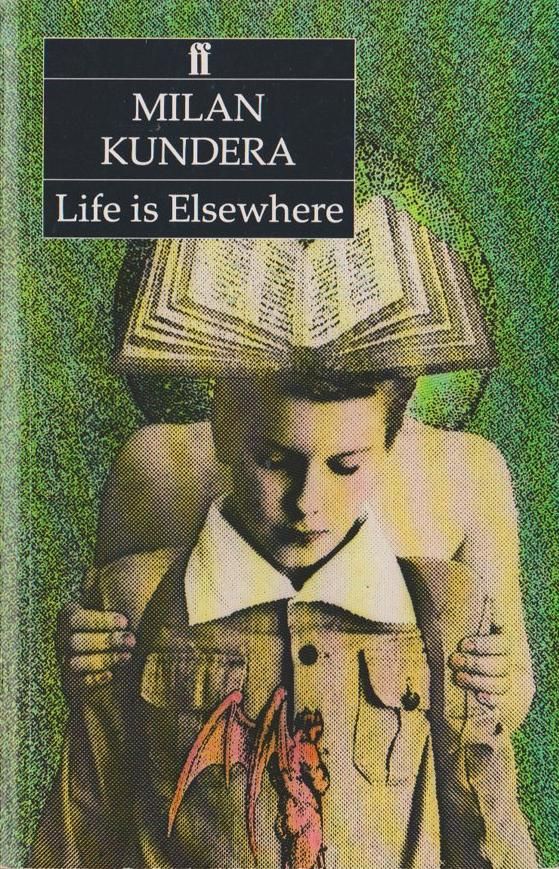

DC: You also created some very important book cover designs in London for Central European novelists like Milan Kundera. Was there an affinity between your visual language and their literary imagination?

AK: Yes, that’s true. But of course, there was no need for posters. I did a few, for, you know, fringe theatres. But I could see that book publishing was a better outlet and that the art director, John McConnell, at Faber and Faber publishing house was commissioning nice covers. His way of working was to match up a very distinctive illustrator with a writer. So when a new Kundera book was published, I did the cover. Likewise with Mario Vargas Llosa and Rachel Ingalls, a great short story writer.

DC: It seemed to me, as a reader of those books at the time, that you had a different visual sensibility to others in London. Your designs always stood out because of their taste for mystery and the surreal. You were outside the mainstream.

AK: That’s right. And I could indulge in a sort of laboratory situation where I could develop this language further. Later, I found that certain materials that I used to get these half-dot screens and to lay interesting colours under the image were being discontinued by Kodak and German manufacturers. I still had a few Orwo films from Poland. But that stock was running out, and so I had to alter my way of working. I didn’t mind: change keeps you fresh.

Later on, I started getting restless too. I wanted to do things which maybe were more controlled, without having to work in a darkroom. That coincided with my starting to teach at the Royal College of Art in London, where the digital techniques became very popular, and colleagues were trying to persuade me that the new technologies would be paradise in the production of new kinds of montage. But what put me off was the infinity of possibilities — too many possibilities. That ran against my desire to simplify, to pare things down.

DC: Constraint can stimulate creativity.

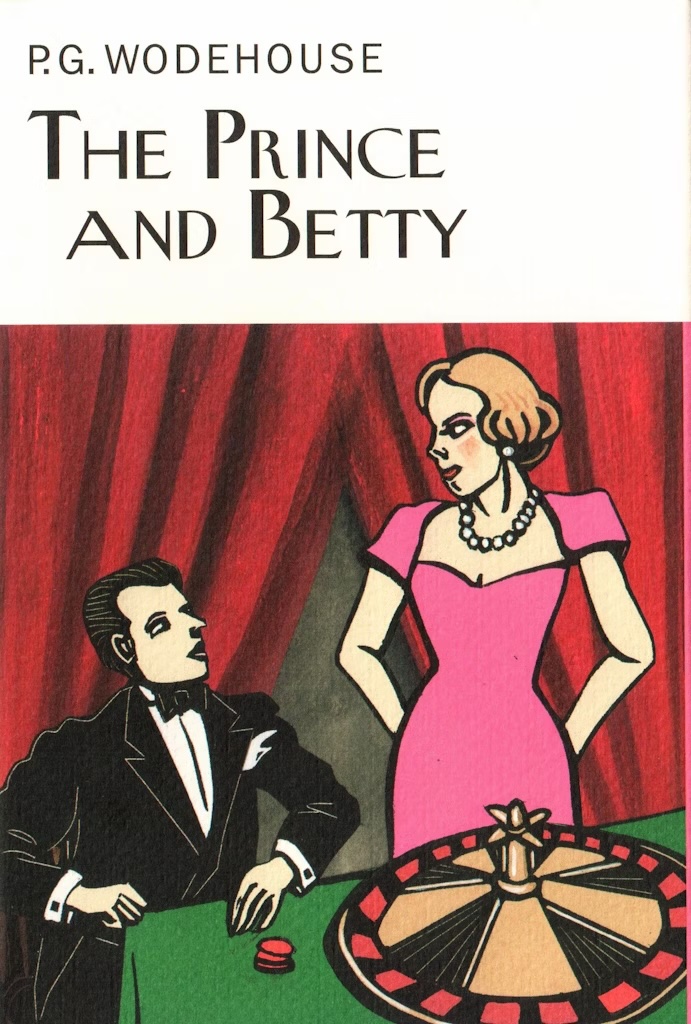

AK: Yes, absolutely. This was very much the case in Poland. And so I thought, ‘I’ll make a decision: I’ll go the other way.’ So, I started doing ink drawings, black and white, lino cuts later, woodcuts. I wanted to avoid being trapped by my own work. So when the opportunity to do something completely different arose — to design the covers of a new edition of P. G. Wodehouse’s books — I seized it. And of course, I like P. G. Wodehouse [a writer who satirised upper class life in Britain in the 1920s and 1930s – DC]. He’s hilarious and playful with language, and it gave me the opportunity to put colour into the lino cuts and do something much more light-hearted than the dark surreal works that I was known for. I did ninety-nine covers in the end.

DC: They look amazing all together.

AK: They do, because sometimes you see them in bookshops in one display, and that always gives me a kick.

DC: What about the step into graphic novels? How did that happen?

AK: That happened with my collaboration with Faber and Faber, because they were involved in launching a new London literary festival with great patrons like Harold Pinter and Brian Eno. Faber and Faber wanted me to create the promotional graphics for the festival. And so I invented a little logo of a naked flying man with an open book on his back in the place of wings.

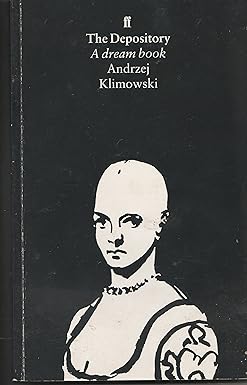

We used to meet to discuss how to raise money for the festival. Eventually, we had to give up because it was the height of the recession. But I was left with this little flying man, and I did some drawings, some wood linocuts with him in different situations, and in the end he started living a life. This became my first book, The Depository, which is just a brush and ink picture story without text — a bit like the works of Frans Masereel, the Belgian artist and illustrator.

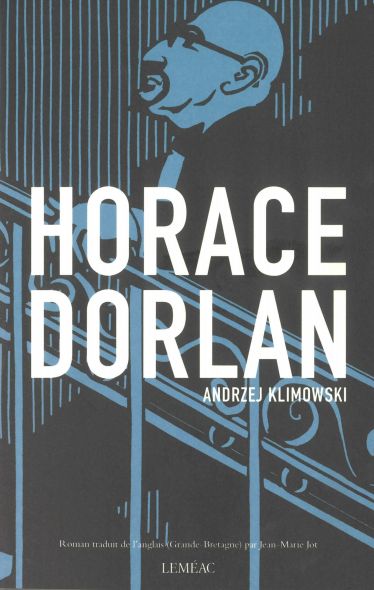

When I’d completed two-thirds of The Depository, I took a chance and went to see Matthew Evans, the chairman of Faber and Faber. And I said, ‘Look, Matthew, I’ve got an idea for a book myself.’ So we looked at the material together and he liked it, and he called in the accountant who worked the figures, and then Matthew said, ‘Okay, go on with it.’ And then later, I did a second book, The Secret, and a third book, Horace Dorlan.

DC: How do you plot a book which is all images? Do you have a storyline that you follow?

AK: No. It’s a stream of consciousness. I do surround myself with images and I know they’re going to play some kind of role or influence on the narrative. But what keeps me going is not knowing where this narrative is heading. That’s what makes me excited. And also it’s risky. I may end up with nothing. But as a book progresses, one image leads to another, or sometimes I juxtapose or remove images. And so it continues. And that’s what gives me a kick, because I myself want to find out what happens at the end.

DC: Do you reject a drawing sometimes?

AK: Yes, if they are just too beautiful in themselves, you know. I get carried away with composition and so on. That’s why, to a certain extent, the black and white avoids that. When you bring in tone, you can get lost in the detail.

DC: So is black and whiteness a controlling mechanism? Another constraint?

AK: It is, but somewhere in my image is the influence of Film Noir, which I’ve always loved — American movies from the 1940s and 1950s that are so sparse, and things happen in the shadows. They were often shot very quickly, with good directors but small budgets. With just a few lights and handheld cameras, the shots often presented odd angles which meant that the viewer had to imagine the space too.

DC: Blackness appears in various ways in your work. In Edifice, your new book, the cloud is not white, but black, right? In The Secret, we go into the darkroom through a Black Square, a reference to Kazimir Malevich’s famous modernist painting.

AK: So everything starts from nothing, you know. I like that risk of really starting from nothing. I suppose that somewhere, also, in my character — and this might be a negative rather than a positive trait — is a sense of panic, a sense of fear, of not getting it right.

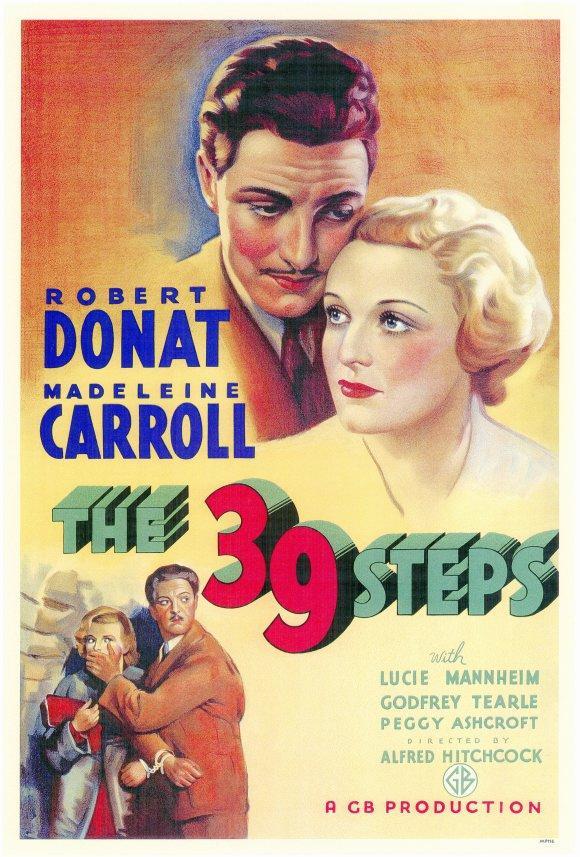

I like Alfred Hitchcock’s film The 39 Steps. There’s a scene in there where the main protagonist has to go to Scotland to investigate a murder that he’s wrongly been accused of. And he escapes police custody, but he’s still got a handcuff around one of his wrists.

He is about to be nabbed by the police on the street, so he goes through a door and finds himself in a hall where a political meeting is taking place. The crowd turns around and applauds him, thinking he’s the politician who’s been invited to talk. So he takes to the stage, where he’s expected to say something, still hiding his handcuff, So he’s improvising all the time. He’s asked a question from the floor of the hall and, with quick thinking, he manages to answer. That’s a bit like doing a book: it’s about getting away with it.

DC: Because you work with drawings rather than words, books like The Secret have a special quality. Words seem much more concrete, very linear. And in your picture books there is always a little uncertainty about whether the story is locking into place or whether the reader is about to be taken somewhere else entirely. They remind me of the knight’s move, a concept invented by an early 20th-century Russian writer called Viktor Shklovsky. He said that ideas can either travel in straight lines — which is a predictable path because the approaching horizon is visible — or they can be like the knight on the chessboard, which travels at angles and jumps over obstacles. Non-linear jumps like the knight’s move can connect unexpected things. Your books have this special quality, I think.

Tell me about your approach to drawing.

AK: I’ve always drawn, but I think that now I know more what I want to get out of drawing. Of course, I’m not a virtuoso. Some people can just draw anything; that comes naturally to them. With me, it’s a bit of a struggle and sometimes, halfway through, I know it’s not going to work, so I have to invent something inside that drawing, or make it different. Chance and surprise is where the excitement lies.

DC: The drawings are very beautiful in Edifice, and they have a different quality to your earlier works — a softer quality with more grey.

AK: That’s right. I discovered a pencil through a friend of mine, Steve Braund, a wonderful illustrator. He showed me this pencil he was using because I liked one of his little booklets. It’s a sort of waxy pencil, like a lithographic pencil. I would do more lithography if I had the opportunity. It affords a kind of smoky, ethereal line. But it can be tricky too: lithographic images can be too washed out, so you have to introduce some dense blacks.

DC: When I look at your books together, I sense lots of echoes and correspondences. And of course that’s natural — you are their author author all. But the echoes seem deeper than that. The same characters and names occur and recur. Horace Dorlan and the Sphinx return in Edifice. Why?

AK: I don’t know. I think they’re just people and things that I haven’t shaken off. Sometimes you try to exhaust something, but if you’re still fascinated by it, it will creep in. Twenty years ago, I made a film in Dublin in Ireland called The Sphinx. When the producers interviewed me about the project, they asked, ‘Where does the Sphinx come from?’ I said, ‘Well, it comes from an Oscar Wilde poem,’ and I recited the first three or four stanzas.

That was a great start, but I ran into a great many problems. I didn’t budget it properly, and I didn’t really see eye to eye with the producers. The film was nicely shot, but I never show it. I can’t even show it, because it doesn’t belong to me. There have been other projects which were never completed too, but Edifice knits them together.

DC: Are these recurrent themes and characters autobiographical in any way?

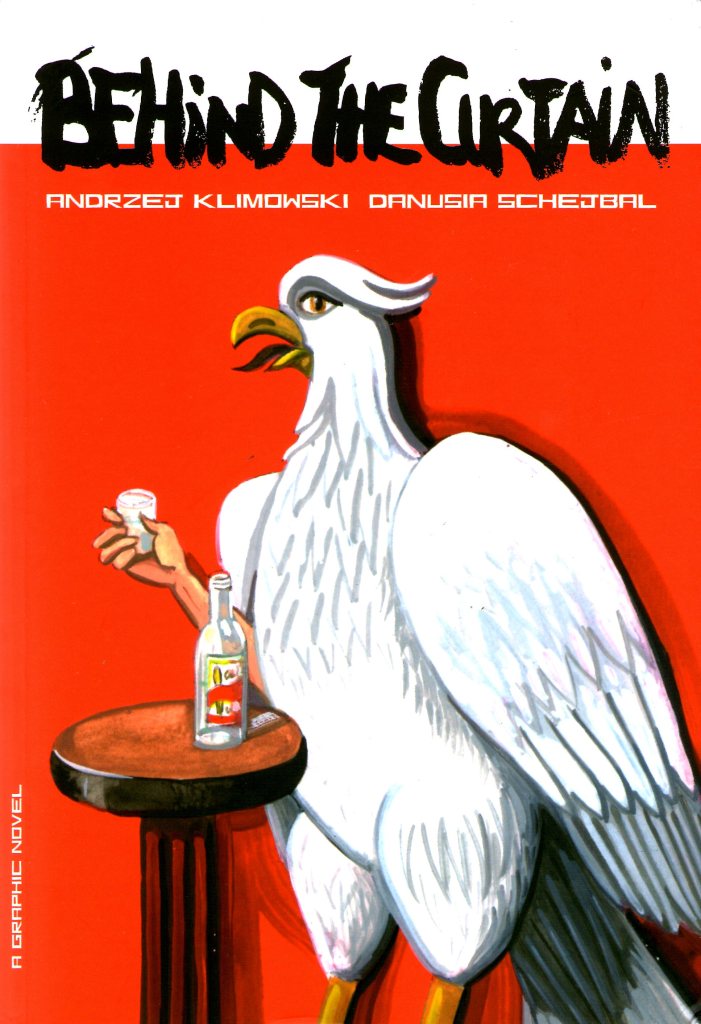

AK: Perhaps. It’s fair to say The Secret is autobiographical, at least to a certain extent. Yes, the business of raising a family and surviving is somewhere in the book. And, of course, the most autobiographical book is the one made with Danusia, Behind the Curtain. We created that because of a conversation we once had — after a concert of Penderecki’s music in Canterbury Cathedral in England — where we started reminiscing about how bizarre life had been in communist Poland in the 1970s. Looking back, life then seems totally absurd. But surrealism was the reality of life in Poland at that time. But if the world is mad, then perhaps you can remain sane. And if everything’s too normal, you can get lost.