A version of this essay is published in a book to accompany Ilona Keserü’s exhibition at Muzeum Susch (details here)

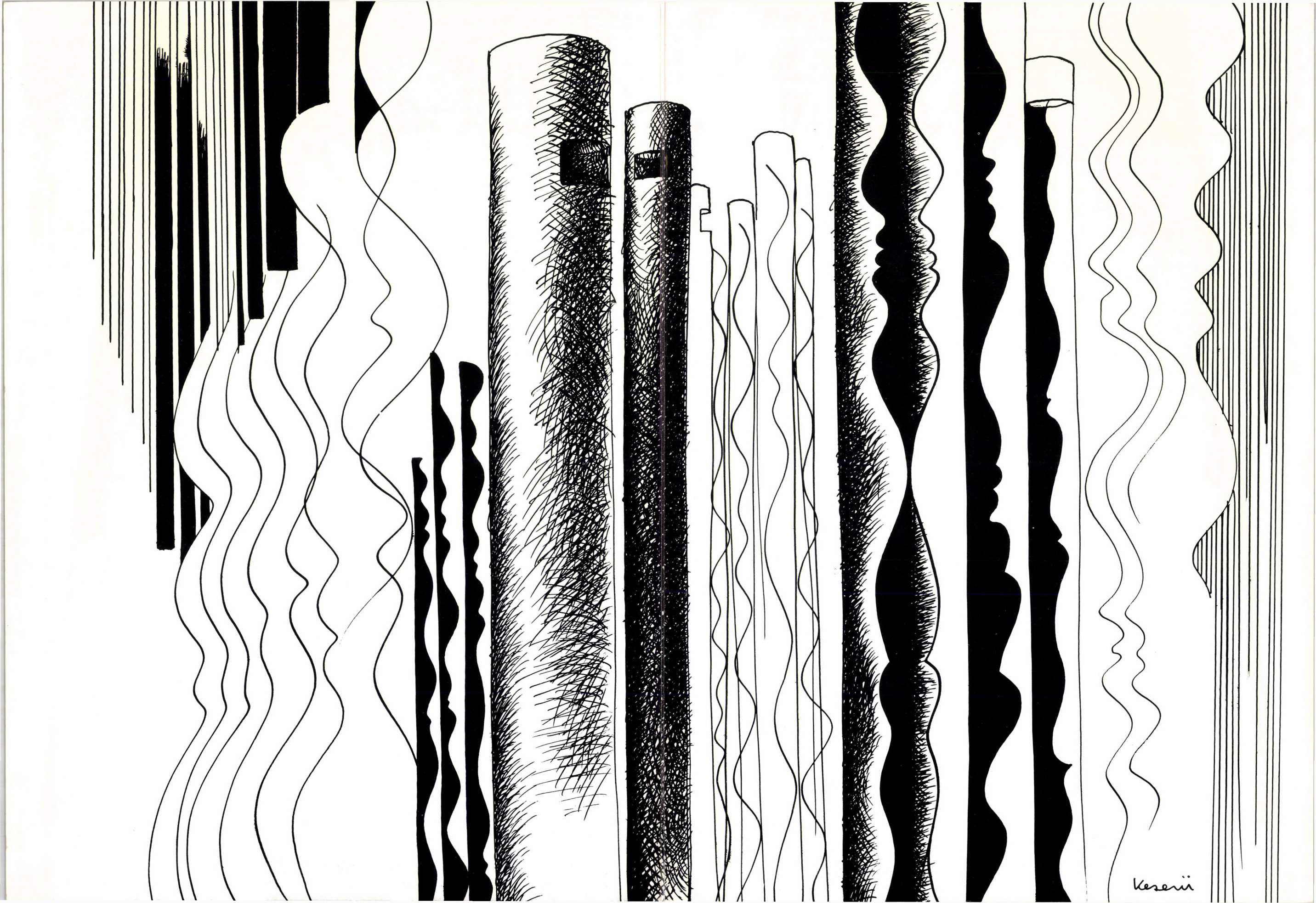

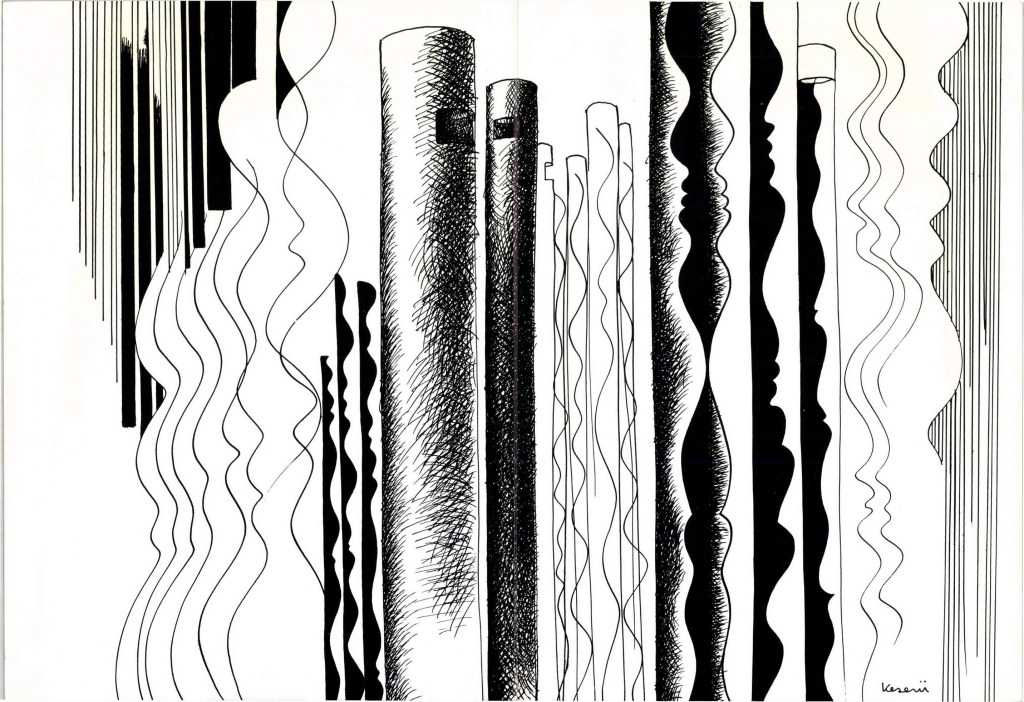

In 1981, Keserü, working in partnership with her husband, the composer László Vidovszky—created one of her most ambitious works to date, an installation that they called Sound-Colour-Space (Hang-szín-tér). In preparation for it, she painted dozens of acoustic pipes in precise monochrome colors in her studio in Szentendre. Each was tuned to a different pitch within the range of a single octave. These slim PVC tubes were designed to be suspended from the ceiling by invisible threads in a hexagonal formation (fig. 1). The one hundred and twenty-seven three-meter-long pipes were then organized according to a classical color wheel, with the strongest hues at the edges of the hexagon, and white—the brightest point and the highest-pitched note—at its center. When he experienced Sound-Colour-Space, critic and curator László Beke saw a line of ideas about chromatics and tonality, which had been linked by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at the beginning of the nineteenth century and has fascinated artists and composers ever since.[1]

Sound-Colour-Space was first installed in the grand cupola of the Magyar Nemzeti Galéria (Hungarian National Gallery) in Budapest in 1981; and then again, in June 1982, at Műcsarnok, Budapest’s kunsthalle (fig. 2). In Műcsarnok, the pipes were hung eighty centimeters apart and almost floor to ceiling, the vertices forming a tight chromatic grille. Visitors were invited to take their own path through the installation while the pipes sounded “automatically” in long whistling pulses (a mechanism created by kinetic artist István Haraszty). When walking along the perimeter, audiences experienced the mix of primary colors shift on the color spectrum as well as the lowest notes; or when following the diagonal lines intersecting the center, they felt the intensities of color and sound rise and fall. What experiencing the work was like is difficult to capture today. But it was very widely reported, and its reviewers shared their feelings willingly and frankly, often coming to very different conclusions. For Beke, a champion of neo-avant-garde art, Sound-Colour-Space was “all meticulously calculated yet evoked strong sensory and emotional responses in terms of both color and sound”[2]; András Bán in was far less enthusiastic in his review published in Magyar Nemzet newspaper: “All this is understandable . . . but not enjoyable: the sound solution of the current presentation does not resemble the music of the spheres, it is not an immaterial sound, not a delicate transition of sounds . . . The most fitting term for the space itself is—disorder.”[3]

In the publication accompanying the Műcsarnok installation, Keserü and Vidovszky characterised Sound-Colour-Space as an experiment that combined their distinct and separate preoccupations at the time:

The origin of this collaboration can be traced back to two activities that we previously carried out independently. One is the detailed and accurate development of the transitions of the colors of the spectrum, and the other is the division of sound into more detailed categories, unlike traditional patterns of perception. It seems that these two types of research share some sort of—perhaps not precisely definable—kinship, as we both had the idea to somehow connect them.[4]

Vidovszky, a composer with a keen interest in the ideas of John Cage, had been one of the founders of the New Music Studio (Új Zenei Stúdió) in Budapest at the start of the 1970s (of which more below). He had a declared interest in microtones, and thus in extending the customary system of intervals found in Western music, the twelve-tone scale.[5] Likewise, Keserü described her art at the time as being an investigation of the fine gradients of color: “Since 1973, the topic of my images has been the breakdown of color (színbontás). My color theory paintings are didactic ones. I work with the colors of the rainbow and with the colors of skin.”[6] Early trials include Space Taking Shape (Alakuló tér), 1972,in which she painted hexagonal patches of “pure” colors on the rolling surface of a corrugated canvas (fig. 3). As if in a puzzle, she determined the color of each patch in steps, each patch one shift away from its neighbor. Since her color paths started from a number of points, her instinctive harmonic system eventually produced clashes. By placing her hand over these discords, she saw that skin tones could “mediate” between jarring colors.

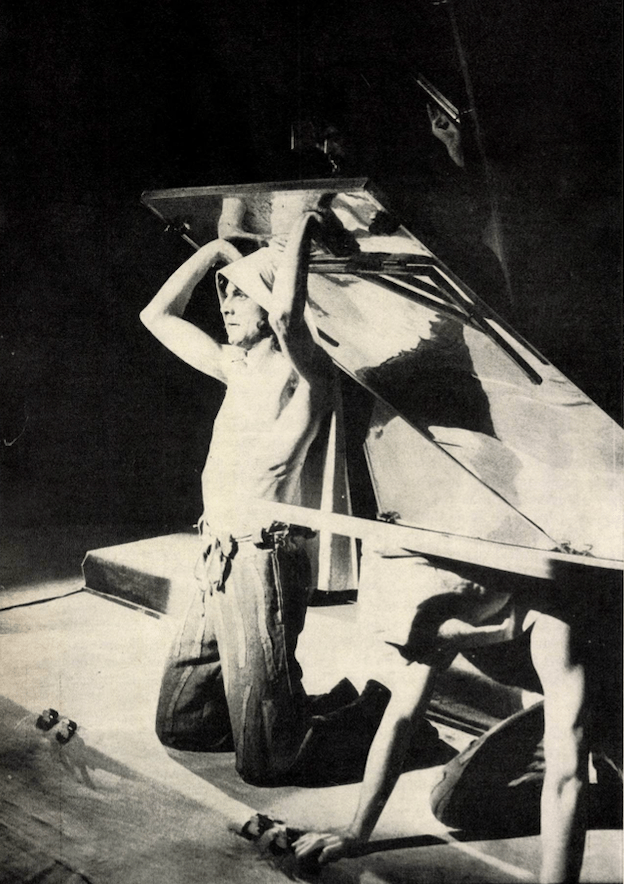

This “discovery” guided many of her color explorations in the years that followed. They included her designs for theater—a key occupation for her at the time. She designed, for instance, the costumes and scenography of the 25 Szinház theater group’s production of M-A-D-Á-C-H, an adaptation of Imre Madách’s monumental play, The Tragedy of Man (1861), in the cramped theater space in the headquarters of the Union of Journalists in Budapest in 1974. The youthful company had been established four years earlier, declaring an interest in the revolutionary tradition of what Brecht called “dialectical theater.” In M-A-D-Á-C-H, performers in Keserü’s monochrome “costumes”—“from the actors’ hair to the soles of their feet [in] the colors of the rainbow”— acted on a skin-colored carpet in the first scene (fig. 4). Reviewers noted that the stiff costumes functioned as a constriction, inhibiting the natural movement of the characters, and detected in this an echo of the historic avant-garde interest in strangeness.[7] The props included large, probably aluminum, mirror-like panels, which the actors used to expand and limit the space on the stage.[8] Keserü welcomed the tight setting: “The small hall of 25 Szinház brings the viewer and actor closer. This circumstance is enhanced by the exchange of the auditorium and the stage, so that the spectator passes through the stage upon entering.”[9]

Audience and performers were drawn even closer on New Year’s Eve 1977 when Keserü mounted a festive happening in the Applied Arts Museum in Budapest. She stitched a massive cloth “sheet”— almost twenty meters in length—from panels in a pinkish hue and the colors of the rainbow. It was stretched on a circular frame to create a temporary Colour-Space (Szín–Tér). Participants were encouraged to assemble this structure, and photographs documenting the event show them playfully pulling the fabric into place. All the while, Vidovszky’s music provided an audio background. The event offered a ludic expression of the embodied sensuality that many critics had already discovered in her fleshy “embossed” canvases created from the late 1960s onward (fig. 5). Other witnesses—more critical in tone—characterized the combination of the rainbow scale and ocher-pink tones as solipsistic. This was not “human color” in its diversity, but simply Keserü’s own.[10] Perhaps Keserü recognized this herself, too: Meeting Colour-Groups (Találkozó színcsoportok),1981, takes the form of two standing rolls of canvas painted in oil paint: one featured twisting bands in the colors of the rainbow in a color continuum, while the other presented a graduated range of all human skin tones (fig. 6).

Keserü and Vidovszky were by no means alone at the time in establishing close relations between art and music. A lively culture of exchange operated in what art historians call the “Second Public Sphere” in socialist Hungary, a dynamic zone that formed on the edges of the official culture.[11] Sometimes borrowing the spaces and the resources of clubs, galleries, and other public institutions, temporary forms of expression—like Colour-Space—could be mounted without attracting official displeasure. Artists, theater workers, musicians, and filmmakers formed closeknit communities, sharing an appetite for “alternative” forms of expression uncontaminated by official ideology or the easy diet of popular culture in Kádár’s Hungary. The New Music Studio—founded by Vidovszky, Zoltán Jeney, László Sáry, and others in 1970—was one such “center” on this periphery.[12] Initiated under the patronage of the Communist Youth Organization (Kommunista Ifjúsági Szövetség), the studio was a network of composers and performers who were drawn to experimentation. They treated the conventions of classical music as dogma to be questioned. The use of chance or the imposing of “unmusical” constraints could, for instance, act as triggers for surprise and innovation. Jeney, for instance, turned to different kinds of language systems found in games, texts, meteorological data, and even telex messages to provide nonmusical materials that he could code as musical compositions. Impho 102/6 (1978), a minimalist piece played on shimmering antique cymbals, is, for instance, derived from the telex address of a Tokyo hotel. New Music Studio composers were also drawn to intermediality, rejecting the orderly categories separating the arts. Both Vidovszky and Jeney were commissioned—alongside visual artists including Miklós Erdély, Dóra Maurer, and others—by the multimedia K/3 studio of Gábor Bódy to make short experimental films exploring film language in the early 1970s.[13] Vidovszky also took keen interest in the staging of his compositions. For instance, his 1972 composition Autoconcert (Autokoncert) was, in effect, a highly theatrical installation combining audio and visual elements: a number of musical instruments—cymbals, bamboo chimes, an accordion, and a music box—would be suspended on the stage, like a premonition of the colored pipes in Sound-Colour-Space. As if “played” by invisible performers, Vidovszky required that they all should sound before crashing noisily to the floor one by one. Quite exactly when they would succumb was not evident, adding much to the tension of the performance. The last instrument to be heard on the stage was a music box playing “The Blue Danube,” until it wound down to silence.

The openness of such works was important, too. Indeed, New Music Studio composers often deployed techniques—unorthodox “graphic scores” and the use of “prepared” instruments—to ensure that each performance was unique. Katalin Keserü, the critic and curator of an exhibition of graphic scores by the Studio’s composers in Budapest in 1978, wrote that “the openness of the works [is] often accompanied by the possibility of completely free performance. This is the world of infinite variations. It stems from the realization that interpretations are always individual; there is no single correct approach or performance method, thus allowing the work to constantly enrich itself . . . Like contemporary visual art trends that rely on viewer participation, the work is completed by the viewer/performer.”[14] Vidovszky’s work of the 1970s was open and polysemic, but it was not indeterminate. Autoconcert no doubt contained many allusions—to works by Cage, and surely to those of Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco as well. But perhaps it was the suggestion of invisible and irrational rules that impressed itself most firmly on audiences in Hungary.

That Keserü and Vidovszky characterized Sound-Colour-Space as an experiment is perhaps not surprising: The term had often been used in Eastern Europe under communist rule by modernist artists who wished to avoid conflict with the authorities or to secure access to resources. For instance, it allowed abstraction to be characterised as visual research into perception or as a branch of design rather than “bourgeois aesthetics.” Similarly, participatory forms of Conceptual Art in the 1970s could be offered as pedagogical experiments with social value.[15] While such strategies were not necessarily insincere, they were expedient. By 1981–82, when Sound-Colour-Space was installed, the ideological winds blowing in Hungary were relatively calm. Nevertheless, experimentalism was literally the curatorial proposition behind the display in Műcsarnok. It was one of a number of works that were installed in four rooms of the gallery that June to coincide with a conference called Color Dynamics 82 beingheld in the Hungarian capital.[16] Offered as a new science, Colour Dynamics sought to understand the positive and negative effects of color in the environment on human perception and behavior. Color research—presented at the conference by besuited technocrats from both sides of the Cold War divide—offered itself to Hungarian planners and architects as a service intended to improve the built environment and human wellbeing, and, as such, a useful tool in socialist urbanism. Both the gray monotony of panel construction housing and the noisy clamor of commercialism could be combated with carefully controlled colour. What was required was the discipline of Colour Dynamics: “With our exhibition,” said Antal Nemcsics of the Construction Science Association (Építőipari Tudományos Egyesület), “we want to draw attention to this: if we ruin the environment’s color scheme now, we will have to bear the consequences for a long time. A painter can easily change the color on a canvas, but for a façade or interior of a building, this is an expensive affair.”[17] In the Műcsarnok Gallery, Nemcsics presented massive three-dimensional model of the Coloroid system of color harmonics that he had developed at the Technical University over two decades: dozens of colored spheres of varying shades of intensity along coordinates of luminosity, hue, and saturation. Here was a tool for designing color-coordinated cities.

Although Sound-Colour-Space was exhibited in the close company of these instruments of design, it is clear that Keserü and Vidovszky were far less interested in matters of practical application than their colleagues in the Construction Science Association. Their understanding of what experimental art might be was much closer to that of Cage, who had written in 1955, “the word ‘experimental’ is apt, providing it is understood not as descriptive of an act to be later judged in terms of success and failure, but simply as of an act the outcome of which is unknown. What has been determined?”[18] Viewed in these terms, Sound-Colour-Space might well be understood as an experiment in perception. It was important to both artists that viewers could determine their own engagement with the installation. Each experience would be different and dependent on decisions made by a particular viewer: the time spent, the route taken, and the associations brought to the work. This reflected both the openness of the New Music Studio ethos and Keserü’s interest in embodiment. And, importantly, the effects appear to have been discordant. Rather than producing a restorative synthesis of color and music, the piece seemed—at least in the minds of its viewers—to point to their breakdown. We know this from the highly descriptive reviews of the installation. Zoltán Nagy wrote: “[S]ound effects cannot be compared to the experiences brought about by colors . . . Firstly, our ears can hardly distinguish between the 127 different pitches within an octave. Secondly, they lack the opportunity to do so, given that many pipes sound simultaneously, blending the diverse sounds into a single common hum.”[19] Critics were looking for clarity and comprehension in Sound-Colour-Space, even for a kind of audiovisual epiphany in which they might lose themselves in “a forest of colors” (színerdő).[20] This, it failed to deliver. But perhaps it never set out to do so. Instead, the piece pointed to discordances and differences, not least between sight and hearing. Vidovszky himself noted: “The difference between the sound and color systems is that the eye can differentiate more easily than the ear, especially in an enclosed space where many other effects must be considered.”[21] Ultimately, what Sound-Colour-Space represented was the curiosity, openness, and interest in experimentation that its creators shared.

[1] László Beke, “Tíz kortárs magyar képzőművészeti kiállítás, 1982 második feléből,” Művészettörténeti Értesítő, 4 (1982), p. 323.

[2] Ibid.

[3] András Bán, “Hang-szín-tér Keserű Ilona és Vidovszky László kiállítása,” Magyar Nemzet, June 16, 1982, p. 2.

[4] Krisztina Jerger, ed., Hang-szín-tér. Keserü Ilona és Vidovszky László kiállítása, exh. cat. Műcsarnok Gallery, Budapest (Budapest, 1982), n.p.

[5] For a good contemporaneous overview of Vidovszky’s practice, see Margaret P. McLay, “Musical Life: The Music of László Vidovszky in London,” New Hungarian Quarterly, 92 (1983), pp. 202–6.

[6] Ilona Keserücited by János Frank, in Keserü Ilona gyűjteményes kiállítása, exh. cat. Műcsarnok Gallery, Budapest (Budapest, 1983), n.p.

[7] Molnár G. Péter, ‘Madách A Huszonötödik Színház bemutatójáról’ Népszabadság 03 (27 March 1974), p. 7.

[8] See András Pályi, ‘Madáchról gondolkozunk’ Szinház 9 (1974), pp. 21–23.

[9] Ilona Keserü, statement published in the 1973–74 program of the Huszonötödik Színház, Budapest (Budapest, 1974), https://szinhaztortenet.hu/record/-/record/OSZMI862022 (accessed in August 2024).

[10] József Vadas, “Ember-szín-tér,” Élet és Irodalom, January 7, 1978), p. 12.

[11] SeeKatalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak, eds., Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-Based Art in Late Socialist Europe (London and New York: Routledge, 2018); and Katalin Cseh-Varga, The Hungarian Avant-Garde and Socialism: The Art of the Second Public Sphere (London: Bloomsbury, 2024).

[12] The position of the New Music Studio within and outside the power structures of culture in the 1970s is brilliantly discussed in Anna Dalos, “Dissidence, Neo-Vvant-Garde, Doublespeak: On the Context of the New Music Studio Budapest in the 1970s,” Musicology Today: Journal of the National University of Music Bucharest 10, no. 1 (37) (2019), pp. 69–78.

[13] The unit was established within the Balázs Béla Studio, a major film production house. See Bódy Gábor, 1946–1985: életműbemutató, ed. László Beke and Miklós Peternák, exh. cat. Műcsarnok Gallery, Budapest (Budapest, 1987).

[14] Katalin Keserü, “Kottaképek,” Bercsényi 28–30 1 (1979), p. 8.

[15] See Miklós Peternák, concept.hu / concept.hu (Paks: Paksi Képtár, 2014).

[16] Another exhibition documenting the use of color in dozens of proposed and realized urban schemes was mounted in the Budapest Gallery. See Tibor Gyengő, “Colour Dynamics ’82. II. Nemzetközi Színdinamikai Konferencia,” Magyar Építőipar 7–8 (1982), pp. 500-501.

[17] Antal Nemcsics cited in P. Szabó Ernő, “Hová szöktek a színek, Monsieur Leger?” Magyar Ifjúság 2 (1982), p. 649.

[18] John Cage, “Experimental Music: Doctrine,” in Silence: John Cage Lectures and Writing (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1973), p. 13.

[19] Zoltán Nagy, “SzínerdőKeserű Ilona és Vidovszky László kiállítása a Műcsarnokban,” Népszabadság, June 23, 1982, p. 7.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Vidovszky cited by Nagy, “Színerdő,” Népszabadság, June 23, 1982, p. 7.