This is a slightly longer version of an essay which will appear in a new anthology edited by Sven Spieker, Socialist Exhibition Cultures, in 2025

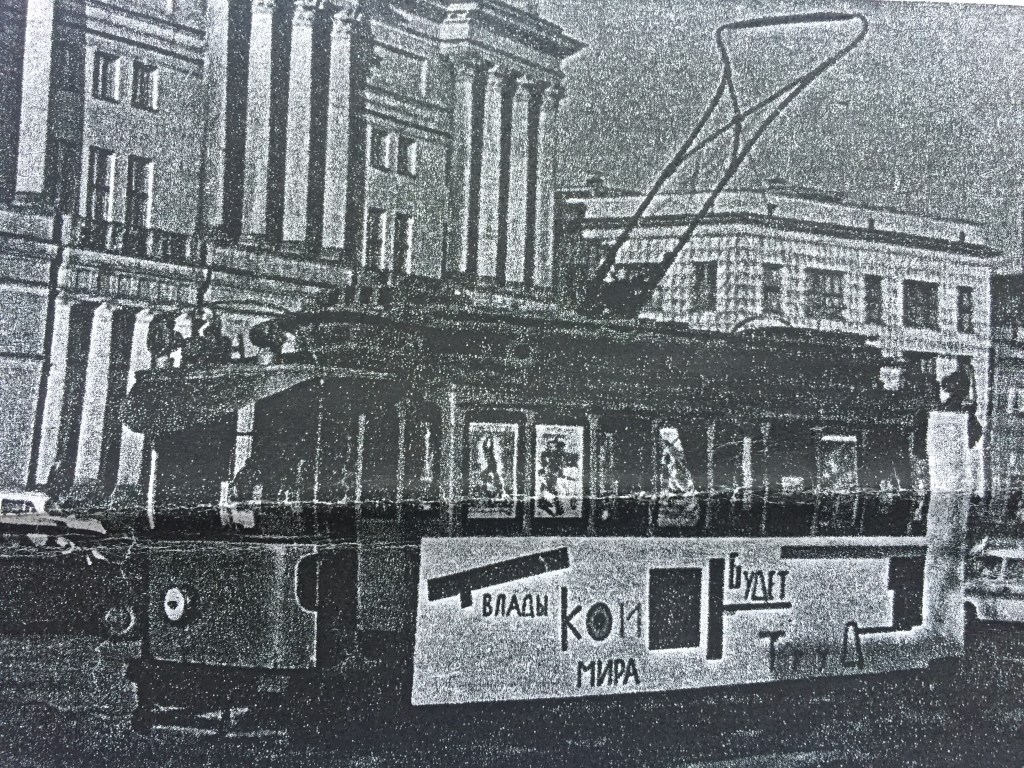

In November 1967 audiences arriving at the Teatr Wielki (Great Theatre) in central Warsaw for a new production of Adam Mickiewicz’s play, Dziady (Forefather’s Eve) passed an old tram car dressed in the kind of agitational-propaganda that had been given to buildings, trams and trains during the civil war that followed the October Revolution in Russia. The slogan ‘Vladykoĭ mira budet trud’ (‘The Ruler of the World will be Labour’) was painted in Russian on its side in block letters under floating abstract forms. An unexpected and temporary monument on Plac Zwycięstwa, the car had been set on the street by the Galeria Współczesna (Contemporary Gallery) which made its home in the theatre complex. It was a highlight of an exhibition entitled ‘Nowa sztuka czasów Rewolucji Październikowej’ (New Art of the Times of the October Revolution). Opening on the anniversary of the historic events in Petrograd fifty years earlier, this exhibition was one red stitch in an enormous flag of commemoration that unfurled across the Eastern Bloc in late 1967. Nearby, the Zachęta National Gallery opened an encyclopaedic survey of ‘revolutionary posters’, a large proportion of which came from collections in the USSR. Elsewhere in the Polish capital, portraits of Lenin decorated the streets and cinemas and theatres gave their programmes over to Soviet themes. Indeed, Dziady had itself been programmed to mark the fiftieth anniversary: with its references to dull-witted bureaucrats and Tsarist despotism, the 1822 play seemed to be in tune with Lenin’s attack on imperial repression.

Celebrating the ambitions of the literary, artistic and architectural avant-garde in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, the show in the Galeria Współczesna emphasised the close connections of revolutionary politics and modernist aesthetics. An introductory panel declared:

Participation of the avant-garde in revolutionary activities, in building a new vision of the life of the people, and also in direct social, political and agitational acts – this is what this exhibition recalls.

Exhibits included prints, books and magazines, photographs and architectural models as well as ceramics from the period before the First World War to the early 1930s. An extensive library of illustrated futurist books and constructivist magazines filled gallery vitrines, below large blown-up photographs on the walls. Few original artworks were available to the curators and so a number of facsimiles were created. Pioneering Polish modernist Henryk Stażewski provided a copy of a painting by Malevich, Suprematist Composition: Aeroplane Flying (1915); and the curators commissioned new models to be made, sometimes by working from grainy images in Soviet publications from the 1920s or the handful of scholarly publications which has been published recently.[1] The Warsaw facsimiles included a model of Gustav Klutsis’s ‘Radio Orator’ loudspeaker stand (version 4, 1923); large models of two of Malevich’s architektons from the mid 1920s, their white forms suggesting future megastructures;[2] a hanging circular construction by Aleksandr Rodchenko of the kind that he had exhibited at the Obmokhu Exhibition in Moscow in 1921; and a new version of Anatoli Lavinskii’s model for a rural reading room that had been created for the Soviet pavilion in the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs in Paris in 1925. Despite the minor status (and small footprint) of the Gallery, this show signalled high ambitions. And as the curators stressed in the exhibition scenario produced for the authorities to review and approve, the exhibition was to be a richly visual experience in which objects and images were to claim priority over texts.[3] Original works were to feature as well as reproductions of ROSTA ‘window’ posters at 1:1 scale, and dozens of colour images would play on automatic slide projectors. While some of the original plans for the show were not, it appears, realised, including the proposal to construct a full-scale propaganda kiosk designed by El Lissitzky alongside the agit-tram, it is clear that the curators wanted ‘Nowa sztuka czasów Rewolucji Październikowej’ to achieve its effects by means of scale and dramatic impact. In the end, the display – on the basis of the photographs taken during installation – was relatively conventional, with most of the exhibits in vitrines or as wall-mounted photographs. A relatively large number of illustrated futurist books featured, some dating back to the eve of the First World War (many the products of artists and poets associated with David Burliuk) emphasising the roots of the Soviet avant-garde in Cubo-Futurist experiments before the Revolution. By contrast, the show had little, at least directly, to say about the end of the avant-garde twenty years later.

The Warsaw show was among the earliest exhibitions dedicated to the Soviet architectural and artistic avant-garde. Other better-known projects include London’s Hayward Gallery’s Art in Revolution: Soviet Art and Design after 1917 organised in 1971 with the involvement of the Ministry of Culture of the Soviet Union, a relationship that was fraught with tension over the display of abstract art (Clarkson, 2018, pp. 15-38). What makes the Warsaw exhibition particularly significant is not only that it was early but that it was organised in Eastern Europe under communist rule. Moreover, it was staged at a time when Soviet museums kept their collections of the art and design of the avant-garde under lock and key. As a number of art historians attest (and artists too), access to non-objective art from the collection of the Petrograd and Moscow branches of Museum of Artistic Culture (est. 1919) and taken into the care of the State Russian Museum in Leningrad in 1926 required special permission or at least the intercession of a friendly curator (Dzjafarova, 1992, pp. 475-81; Dzjafarova, 1993). After Stalin, the avant-garde occupied a state of limbo in which its art was preserved but could not be seen by the public. Only in the early 1960s were some works shown in Moscow in a series of exhibitions under the prudent title ‘Illustrators of Mayakovsky’ organised by the researcher, collector and critic Nikolai Khardzhiev in the Mayakovsky Museum (Petrova, 2002). Shows on El Lissitzky, Gustav Klutsis, Mikhail Matyushin and Pavel Filonov in 1960 and 1961 were followed by displays of artworks by Malevich and Tatlin in 1962 and Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov in 1965. Most of the exhibits in the series came from Khardzhiev’s own remarkable collection of works of art and documents, often acquired directly from the artists or their families. These exhibitions had the aura of the illicit, such was the official disdain for abstract art in the Soviet Union, and their organisation required a kind of tactical alignment with the official ‘cult’ of Mayakovsky, the only member of the avant-garde whose reputation advanced during the Stalin years.

When the interest of Western European museums and commercial galleries in the Soviet avant-garde grew in the 1960s, the response of the Soviet authorities was one of suspicion. The catalogue of the pioneering Tatlin exhibition at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm held a few months after the Warsaw show features an unusual expression of ‘support’ from the Ministry of Culture of the Soviet Union. An extract of a letter from the Ministry to the Museum, it defends the reasons for not lending works to the show (Anderson, 1968). (Soviet museums were, it explained, too busy cataloguing and restoring the constructivist’s work to meet the Moderna Museet’s requests). In consequence, the Stockholm curators – like those in Warsaw in 1967 – relied on reconstructions of a number of the Soviet artist’s works and designs including a model of the Monument to the Third International, the Letatlin flying machine and costumes for the Zanguézi show of 1923 (Leleu,2007).

Preserved but unseen, the art and designs of the Soviet avant-garde in state collections in the USSR seemed – at least to their guardians – too combustible to be loaned and displayed. They recalled the heady utopianism, relative pluralism and experimentation of the 1920s. In the ideological frameworks of 1967, utopianism was associated by Soviet ideologues with naivety. In the Polish context, ideologues were inclined to stress the classic Marxian distinction between ‘socjalizm utopijny’ (utopian socialism) and ‘socjalizm naukowy’ (scientific socialism). Avant-garde schemes also risked acting as unintended reminders of the repression of the avant-garde during the Stalin years and even the brutal and irrational violence of the regime. Graphic designer Gustav Klutsis and theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold (both of whom featured in the Galeria Współczesna show) were sentenced to death on fictitious charges during the Great Terror and executed only to be posthumously ‘rehabilitated’ during the period of de-Stalinization in the mid 1950s. Even after Stalin’s crimes were decried by Khrushchev in 1956, survivors – who had close ties to the avant-garde – remained circumspect. Polish researcher Szymon Bojko attempted to interview one of Malevich’s closest and most loyal assistants, Konstantin Rozhdestvensky on a number of occasions in the 1960s. Then vice-chairman of the Union of Artists of the USSR with an illustrious career, Rozhdestvensky repeatedly denied being Malevich’s student until the Glasnost era (Bojko, 2009).

‘Nowa sztuka czasów Rewolucji Październikowej’ was an outlier in the Galeria Współczesna’s programme. The gallery had been established two years earlier by the ‘Ruch’ press distributor as a branch in a national network of libraries and cultural centres. As its name signalled, it placed a strong emphasis on experiment and invention. Despite its small footprint and marginal rank in the hierarchy of art institutions in the capital, the Gallery’s programme under the directorship of Janusz Bogucki and his wife Maria Bogucka was bold, embracing new multimedia, performance and installation practices by key neo-avantgarde artists. Bogucki’s ambition was ‘to exhibit the most prominent artists associated with today’s vital tendencies, showing the ability to create creative changes, and on the other hand, young authors who stand out both as an individual and with participation in the process of developing new art’ (Bogucki, 1968, np). Moreover, the Boguckis’ ambitious programme aspired to intellectual and creative autonomy. While state control over culture in Poland was by no means as draconian as that exercised in the Soviet Union, public display of art remained subject to censorship and control. Curators, publishers and other cultural bureaucrats were actively engaged in interpreting – and often policing – an uncertain ‘Party line’. Gallery director Bogucki knew this very well, for in 1959 he had been branded a Trotskyite and forced to resign from his position as editor of the Playstyka (Plastic Arts) supplement to a major literary magazine for displaying a leaflet signed by André Breton and Stalin’s rival, Leon Trotsky, in an exhibition on surrealism in Kraków (Jarecka, 2011, p. 26). Later, in the 1970s, Bogucki was targeted by the Polish secret services and, effectively, forced out of his role as the Gallery’s director, resigning in July 1974 before a planned campaign against the gallery got underway (Piotrowski, 2017). Like others of his generation, his career path arched from conformity in the 1950s to opposition in the 1980s.

The 1967 exhibition was the product of efforts not only by the Boguckis but also by a network of more than a dozen artists, curators and writers, many of whom had been active in left-wing politics before the formation of the Polish People’s Republic in the late 1940s. They included Mieczysław Berman, a designer best known for his political photomontages, and Seweryn Pollak, poet and translator: both lent prints, drawings, books and magazines. Others such as Edmund Goldzamt, an authority on Socialist Realism in architecture acted as curatorial advisors (Goldzamt, 1956; Skalimowski, 2021). Some had spent the Second World War in the Soviet Union, returning to Poland as enthusiasts for Stalinism only to break with the Party during the Thaw of the mid 1950s. Designer, writer and cultural bureaucrat Szymon Bojko, for instance, fits this pattern: returning to Poland from the Soviet Union after the end of the war, he worked as a graphic designer and writer in state publishing, becoming a member of the Cultural Department of the Central Committee in the 1950s (Rypson, 2010). After the Thaw, he shifted roles becoming a kind of free-wheeling and well-connected design critic in Poland and abroad. Bojko was a regular visitor to the Soviet Union as a representative of International Red Aid (MOPR) and as a guest of Soviet design institutes. As noted above, he used these official visits to conduct his own ‘private’ research into Soviet modernism, seeking out surviving members of the avant-garde and their families, and persuading museums and archives to open their collections. The fruits of that research shaped the Warsaw exhibition and had considerable impact abroad when they appeared in his book, New Graphic Design in Revolutionary Russia (Bojko, 1972). Another member of this network of curators, poet Anatol Stern had a close, even personal relationship to the Soviet avant-garde. He lent a large number of his own copies of Russian futurist books by Aleksei Kruchyonykh, Velimir Khlebnikov, David Burliuk, Vladimir Mayakovsky and others published to the Warsaw exhibition, and he spoke at accompanying events including ‘An Evening of Memories of Creators of Leftist Art’ as a closing event. Born at the end of the nineteenth century, Stern was a Futurist poet and gulag-survivor. When the Stalinists took control of Poland in the 1940s, his reputation as a militant avant-garde poet (and his arrest by the NKVD in 1940) made him a suspect character in the eyes of the authorities. Only in 1956, when Stalinism was rebutted across the Bloc, was he able to become a public figure again, publishing his poems and writing memoirs. Much of his activity at this time was dedicated to active rehabilitation of the inter-war avant-garde – particularly the figure of Bruno Jasieński, his futurist ally who had moved to Leningrad in 1929 and became a loyal Stalinist only to be executed in 1938 during the Terror (Stern, 1969). Jasieński did not feature in the Galeria Współczesna show. Nevertheless, the exhibition played a part in what Marci Shore describes as Stern’s project at the time, namely, ‘to show that Polish futurism … had contained within itself a revolutionary impulse from the outset, that while Marinetti had wanted to awaken his nation with a cult of strength, and the French futurists had declined political engagement, the Polish futurists – like their Russian counterparts – had declared rebellion in the name of social justice’ (Shore, 2006, p. 347).

In light of Stern’s project of the rehabilitation of the avant-garde (and rather like Khardzhiev’s exhibitions in the Mayakovsky Museum) ‘Nowa sztuka czasów Rewolucji Październikowej’ is best understood not as a direct expression of what might be called ‘official culture’ but as the product of enthusiasm on the part of figures who enjoyed some degree of autonomy of action in cultural life. Perhaps because of the official nervousness which attached any representation of Soviet culture in the People’s Republic of Poland, ‘Nowa sztuka czasów Rewolucji Październikowej’appears to have been subject to particular scrutiny. Bogucki prepared a list of exhibits, lenders and a detailed exhibition scenario that detailed authoritative sources for all the facsimile exhibits. (The agit-tram outside the gallery, for instance, was based on an image which had appeared in the Soviet periodical Sputnik in March 1967 and so had recently passed the scrutiny of the censor in Moscow, a far higher authority than those in Poland). An attempt to print copies of a black and red poster designed by Włodzimierz Borowski which combined block lettering with a black square invoking Malevich’s most famous work was denied by the Evaluations and Appraisals Committee of the Ministry of Culture and Art.[4] The curators had imagined filling the street outside the gallery with these rousing posters on metal stands. The original title proposed for the anniversary exhibition, ‘Awangarda i rewolucja’ (‘Avant-garde and Revolution’) was not accepted either: seemingly, it was too inflammatory, too prospective. Instead, officials working for the state press agency to which the Gallery belonged demanded the unmistakably retrospective title by which it was promoted (Jarecka, 2011, 26).

These minor obstructions were symptoms of the anxiety that appears to have accompanied all but the most obsequious representations of Poland’s mercurial and dyspathetic Eastern neighbour. The authorities in Warsaw also appear to have been infected by a kind of fear that the past might inflame the present. What triggered this anxiety remains a matter of conjecture. But the answer may be found in the emergence of the New Left – often student radicals – in Poland and their interest in revolution as a living practice and not simply a chapter in history. In 1964, Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski, young lecturers at Warsaw University, had written an ‘List otwarty do partii’ (Open Letter to the Party), a long and thorough Marxist critique of the hold of the bureaucracy on Polish society, one which, in their analysis, effectively had screwed a new ruling class into the seat of power leaving the workers as much exploited as they had been under capitalism (Kuroń and Modzelewski, 1966). For Poland to fulfil its commitment to Communism what was required was an authentic international proletarian revolution in which the workers take power, the army is dismantled, and freedom of speech is guaranteed. Che Guevara and the Viet Cong were the new revolutionaries of the day, according to Kuroń and Modzelewski. Their arguments made it clear that the characteristics of Stalinism –state nationalisation, socialism in one country and rule by an elite – had been little changed by the events of 1956 which had seen new ‘reformist’ communists take power in Poland. What was needed was a restoration of the Bolshevik commitment to internationalism, to self-emancipation and mass participatory democracy.

The response to the ‘Open Letter’ was prompt and decisive: Kuroń and Modzelewski were expelled from the Party, indicted and then tried in camera, sentenced and imprisoned in 1965. This did little to silence their ideas: their letter was translated and reprinted widely abroad between 1966 and 1969. In late 1966, a researcher working for Radio Free Europe, looking for signs of support for Kuroń and Modzelewski’s ideas at home, imagined that a new wave of ‘rebellion’ was about to break (Johnson, 1966). One suspects that the Ministry of the Interior was doing much the same (no doubt with an eye on the reform movement fermenting in neighbouring Czechoslovakia too). In claiming revolution as a creative and political force in the present, it seems likely that the Galeria Współczesna exhibition touched a nerve. In an article entitled ‘Rewolucja i awangarda’ (Revolution and the Avant-garde) published in early 1968, Bogucki wrote that in the art of the Soviet avant-garde, one ‘instinctively and creatively feels the great traditions of Russian art, independent and passionate participation in the fate of the contemporary avant-garde of the world, and uncompromising connection with the matter of Revolution, seeing oneself and sensing its achievements with the perspective of history’ (Bogucki, 1968). Though couching his ideas in terms that hymned Soviet history, Bogucki seemed, nevertheless, to be saying that the ‘contemporary avant-garde’ had yet to fulfil its historic task and that the Revolution was unfinished – the theme of Kuroń and Modzelewski’s ‘Open Letter’. Allies picked up the idea in their reviews too. Ignacy Witz in Życie Warszawy wrote enthusiastically: ‘The new art sought to integrate all creativity. Its elements were poetry and music, theatre and cinema, painting and architecture – all in constant movement, overlapping in continuous fluctuations … The avant-garde quality (awangardowość) of this art is that it is still alive, and, importantly, still contemporary’. After somewhat cautiously referring to the hostility faced by the Soviet avant-garde during the Stalinist years, Witz continued: ‘Many of the precepts and discoveries of the Russian avant-garde have been realized: while others still wait to be realised at the scale of the dreams of their creators’ (Witz, 1972, pp. 279-80). Here, the revival of Soviet utopianism was augured.

Invoking Mayakovsky’s famous declaration of ‘Streets – our brushes. Palettes – our squares’ in his review, Witz emphasised the drive to escape the walls of the gallery to engage with life as a feature of the early days of the Soviets and the present day in Poland. In the event, it was not the anniversary exhibition in the Gallery but the commemorative performance of Mickiewicz’s Dziady in the Teatr Wielki that was the trigger for rebellion on the streets. Early performances of the poetic drama which relays the cruelty of Tsar Alexander and the persecution of Poles in the 1830s were met with loud cheering in the audience. Party ideologues became concerned that the Soviet embassy would understand that anti-imperial themes in Mickiewicz’s drama had been transposed into anti-Soviet feeling, and so cut the run of the play short. The final performance in January 1968 became a confrontation when protesting students marched from the theatre to the statue of Mickiewicz on Krakowskie Przedmieście nearby. A play mounted to celebrate fifty years of Soviet rule became the trigger for what is known as the ‘March events’ – a conflict between students and the state. Protests and occupation of Warsaw University buildings demanding intellectual freedom in the weeks that followed were put down with force by thugs characterised ‘loyal members of the working class’ in official rhetoric (Osęka, 2015). Factions in the ruling party also set a storm of anti-Semitism in motion, characterising the students and their supporters as ‘Zionists’ thereby triggering a kind of purge of its own ranks and propelling the mass emigration of a large part of Poland’s remaining Jews. (One of those forced to leave was a member of the curatorial team which mounted the ‘Nowa sztuka czasów Rewolucji Październikowej’exhibition, Samuel Fiszman, a scholar who led the Slavic Studies Department of the Polish Academy of Sciences and left for the US in 1969).

‘Nowa sztuka czasów Rewolucji Październikowej’is a forgotten episode in the history of exhibitions despite the fact that it has a strong claim to be the first survey of the Soviet avant-garde. Overshowed by events in Poland and elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc in 1968 which shattered illusions about the prospect of reform and led to the formation of the anti-communist opposition in Poland in the 1970s, it is not surprising that it is little known or discussed. Official anxieties about the capacity of an exhibition in a theatre to enflame revolutionary sentiments were misplaced, it seems, but not entirely wrong: after all, the performance of a nineteenth century play in same theatre appears to have had an incendiary capacity. Nevertheless, the exhibition points to the deep and sincere fascination which some parts of the intelligentsia in the People’s Republic felt for the alliance of art and politics that marked the Soviet avant-garde as well as the corruption of ideals that they detected in contemporary Soviet culture. For Stern – in his last year of life – this was framed by an autobiographical desire to rehabilitate his own past and that of his friends and allies. For some of his Galeria Współczesna co-curators including Bojko and Bogucki, the exhibition marked an important staging point on a path which was to take them to the independent culture that formed in parallel with the Solidarity movement at the beginning of the 1980s – another meeting of art and politics.

Bibliography

Troels Andersen (ed) Vladimir Tatlin, exhibition catalogue (Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1968).

Janusz Bogucki, “Pokaz zbiorowy prac artystów uczestników wystaw Galerii Współczesnej w latach 1965-1968,” exhibition catalogue (Warsaw: Galeria Współczesna, 1968). np.

Janusz Bogucki, “Rewolucja i awangarda,” in Kultura, no. 1 (7 January 1968)

Szymon Bojko, New Graphic Design in Revolutionary Russia (New York: Praeger, 1972).

Szymon Bojko, “Kazimierz Malewicz – bohater tragiczny?” (May 2009) available online at www.obieg.pl – accessed July 2021.

Verity Clarkson, “The Soviet Avant-Garde in Cold War Britain: the Art in Revolution Exhibition (1971),” in: Simo Mikkonen, Giles Scott-Smith and Jari Parkkinen (eds.), Entangled East and West: Cultural Diplomacy and Artistic Interaction during the Cold War (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2018), pp. 15-38.

S. Dzjafarova, “The Creation of the Museum of Painterly Culture,” The Great Utopia. The Russian and Soviet Avant-garde 1915-32 (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of Art, 1992) pp. 475-81.

S. Dzjafarova, “”Une Politique de diffusion de l’art moderne – Les Musées de la Culture Artistique” in : L’Avant-Garde Russe – Chefs d’oeuvres des Musées de Russie 1905-1925 (Nantes: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1993).

Edmund Goldzamt, Architektura zespołów Śródmiejskich i problemy dziedzictwa (Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1956).

Dorota Jarecka, ‘Janusz Bogucki, polski Szeemann?’ in Karol Sienkiewicz (ed.) Odrzucone Dziedzictwo. O sztuce polskiej lat 80 (Warsaw: Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej, 2011) pp. 8-31.

A.R. Johnson, “Kuron and Modzelewski’s ‘Open Letter to the Party’,” Radio Free Europe Report (16 November 1966) p. 12 – available at https://proxy.europeana.eu/ accessed online July 2021.

Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski, “An Open Letter to the Party I,” in: New Politics (spring 1966); pp. 5-46, and ‘An Open Letter to the Party II’ in: New Politics (summer 1966), pp. 72-100.

Nathalie Leleu, “The Model of Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International: Reconstruction as an Instrument of Research and States of Knowledge’” in: Tate Papers, no.8 (autumn 2007) available at www.tate.org.uk/research/ accessed online 29 July 2021

N. Petrova (ed.) A Legacy Regained: Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Russian Avant Garde (St Petersburg: Palace Editions, 2002).

Kazimierz Piotrowski, “Obywatel sentymentalny. Janusz Bogucki w ‘totalnej niemożliwości’,” in: Alicja Kisielewska, Monika Kostaszuk-Romanowska, Andrzej Kisielewski (eds) PRL-owskie re-sentymenty (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Katedra, 2017) pp. 197-211.

Piotr Osęka, My, ludzie z Marca. Autoportret pokolenia’68 (Wołowiec: ISP PAN, 2015).

Piotr Rypson, “Inżynierowie oczu: Prasa Pop Wojskowa” in: Piktogram 14 (2010) pp. 14-27.

Marci Shore, Caviar and Ashes. A Warsaw Generation’s Life and Death in Marxism, 1918-1968 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006).

Andrzej Skalimowski, “Edmund Goldzamt (1921–1990). Refleksyjny dogmatyk,” in: Kwartalnik Historii Nauki i Techniki 66, no. 4 (2021) pp. 171–189.

Anatol Stern, Bruno Jasieński (Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna, 1969).

H. Syrkus, “Kazimierz Malewicz” in: Rocznik Historii Sztuki 1, no. 1 (1976) pp. 147-158.

Andrzej Turowski, Malewicz w Warszawie: rekonstrukcje i symulacje (Warsaw: Universitas, 2002).

Ignacy Witz, “Nowa sztuka czasów rewolucji,” (Życie Warszawy, 24 November 1967) in: Ignacy Witz. Przechadzki po warszawskich wystawach 1945-1968 (Warsaw: PIW, 1972) pp. 279-80.

[1] The main reference sources for these facsimiles were the German edition of Camilla Grey’s 1962 book, The Great Experiment. Russian Art 1863-1922 and articles in two issues of Dekorativnoe Iskusstvo SSSR no. 2 (1961) and no. 5 (1966), a Soviet periodical dedicated to applied art.

[2] Andrzej Turowski identifies one of the architectons to be a copy of Zeta (1923-7), a work that had been given by Malevich to Polish architects Helena and Szymon Syrkus (Turowski, 2002, p. 290). Helena Syrkus recalled that the model had survived the war, but was lost or stolen in Warsaw in the winter of 1946 (Syrkus, 1976, p. 153).

[3] The archives of Galeria Współczesna are held by ISPAN (Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences), Warsaw.

[4] See the letter dated 13 November 1967 from Maria Bogucka to Wojciech Wilski, Plastic Art Division, Ministry of Culture and Art appealing the decision. Bogucka’s appeal seems to have been successful and the decision was overturned in a response from the Ministry dated 18 December 1967, after the exhibition’s closure. A copy of the poster – printed without exhibition dates – is in the Galeria Współczesna Archive, ISPAN.