This is a draft of an essay which appears a shorter version in a book accompanying “L’Âge atomique” exhibition curated by Julia Garimorth and Maria Stavrinaki for the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris – October 2024 to February 2025.

In late 1962 an exhibition marking the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Moscow Union of Artists opened in the Manezh exhibition hall in Moscow. A large state show, it included the work of young artists, Yurii Sobolev, Ullo Sooster, Ernst Neizvestny and Vladimir Yankilevsky, who were later to be called non-conformists and denied opportunities to exhibit their art. Gathered together by Eli Beliutin, an artist and teacher at the Moscow Polygraphic Institute, these young artists had already presented their new, sometimes abstract works in minor venues run by reform-minded organisations like student clubs.[1] A three-day show in the Teachers’ House earlier that year had been a sensation, drawing reporters from the Western media searching for signs of change in the Soviet Union after Stalin. Now in the Manezh, a prestigious venue in Moscow, their art was like a litmus test for Khrushchev’s reforms. Yankilevsky’s semi-abstract paintings Atomic Station (1962) and Two Principles (1962), Neizvestny’s macquettes of contorted figures, and Sooster’s surreal renditions of human eyes were lined up against the history paintings of the Soviet academicians and works in the gritty ‘severe’ style that was a marker of a new order of realism after Stalinism. In what is now a notorious episode in the history of modern art in the Soviet Union, Khrushchev toured the galleries with other members of the Central Committee, meeting many of the exhibiting artists. The First Secretary of the Communist Party’s response to the young modernists was an expletive-filled tirade laced with threats of exile and hard-labour.[2] Yankilevsky’s attempts to explain his art were in vain.

Perhaps the seeming disjunction between Yankilevsky’s pentaptych and its title, Atomic Station contributed to the Soviet leader’s ire. Atomic power was a loudly-trumpeted field of Soviet progress at the time. It promised, for instance, to sustain climate-controlled life in city-sized megastructures in the frozen zone above the Arctic Circle, and would drive the deep exploration of the Cosmos.[3] Soviet applications of nuclear fusion were invariably presented as measures of its commitment to peace and progress (and, conversely, the American nuclear programme was presented as menacing ambition). It was also fuel for a revival of techno-utopianism after Stalinism. ‘The possibilities of a free Soviet man are unlimited,’ declared Khrushchev. ‘He created the seas, and tames the atom, he flies to neighbouring planets. There are no shackles, nothing holds back his dreams, his impulses, his creativity.’[4] In 1962 Atomic Station was surely a first-class theme for Soviet art. Yet, Yankilevsky’s five canvases —spanning six metres — ‘fail’ to represent the subject of their title, at least according to the Kremlin’s ideological script. Hovering at the threshold of ‘pure’ abstraction, the five panels suggest a landscape from the air — patchworks of fields and meandering rivers and islands, as well as the footprints of human-made structures. Some canvases are flooded with verdant greens and watery blues while others suggest parched fields and charred shadows. But where was the Atomic Station promised by the title?

Aerial views were a new and sometimes chilling feature of the visual imaginary of the era. Reconnaissance satellites and high-altitude surveillance planes were recording new perspectives of the landscape. Citizens of the Soviet Union were given a disconcerting introduction to this branch of Cold War optics in May 1960 when a USA U-2 spy plane was shot down by a S-75 Dina missile over Sverdlovsk, 1800 miles east of Moscow. Pilot Francis Gary Power had been crossing the Eastern Urals where the deep foundations were being dug and concrete poured to construct new uranium processing plants, reactors and storage plants. Ten days later, twisted debris from his plane was exhibited in Gorky Park in Moscow alongside surveillance photographs from the camera which had been fixed on its underside. Visitors were invited to ‘decrypt’ American images of Soviet territory, repeating the work of CIA operatives in the National Photographic Interpretation Centre in Washington.

A similar invitation was, it seems, offered by Yankilevsky in his Atomic Station pentaptych. Organised as five panels, the format encourages comparison: the eye flits between desiccated landscapes and the flowing rivers and verdant fields. In the right-hand panel, dark lines mark a charcoal zone around a structure which looks more like the scene of an explosion than a site of construction. Wary of literal readings of his art, Yankilevsky did not, it seems, explain his vision of atomic power. Many years later he called the left panel ‘Landscape’ (Landschaft) and described it as an ‘entrance’ or, in cybernetics, an ‘input’ (‘vkhod’); and he described the disconcerting ‘cosmic landscape’ on the right that he called ‘Premonition’ (Predchuvstvie) as ‘vykhod’, a word that can mean both an ‘exit’ and ‘output’.[5] Was it possible that in 1962 he’d heard rumour of the accident that had occurred a few years earlier in Mayak, a plutonium processing facility located near the closed city of Chalyabinsk-40? The plant had been constructed after the Second World War to process the plutonium required for Soviet nuclear weapons.[6] Initially, nuclear waste was pumped into the network of the rivers in the region. When its toxic effects became apparent, underground tanks were constructed. One exploded like a massive volcano in September 1957, and a vast area of the Eastern Urals was contaminated, triggering the evacuation of 10,000 people and the mass slaughter of livestock and wild animals. To stop the spread of radioactive materials, monumental transformations of the landscape were undertaken in the months that followed: topsoil was buried in massive ‘graves’; rivers were diverted;[7] and homes were destroyed, leaving only standing chimney stacks —a landscape of skewers. Thereafter, travellers were not allowed to enter the zone, with local road signs instructing drivers to pass by at maximum speed.[8]

At the time when Yankilevsky painted Atomic Station, the authorities had screwed a tight seal of silence around the catastrophic events at Mayak. Yet the mortifying potential of nuclear disaster leaked into Soviet culture. Set in a secret research institute in Siberia, Mikhail Romm’s 1962 movie Nine Days in One Year achieved, for instance, a deft balance of optimism and anxiety. The narrative focuses on a brilliant research physicist who accepts his fate — premature death by radiation poisoning — as the price of scientific discovery. His contribution to Soviet progress is to have achieved a historic thermonuclear reaction. Dreamworld and disaster were broached repeatedly in Nine Days in One Year, as the physicists debate the effects of their work. Ostensibly, Romm’s film was a familiar tale of Soviet martyrdom: namely, the death of a hero to guarantee the future of the collective. But his interest in the risks that attached to the Soviet atomic programme was hardly the official line; nor were the allusions to the ideological management of Soviet science. (When one white-coated scientist insists on the relation of atomic power to atomic weapons, he knows that he may be ‘ruined politically’). Shot in black and white, the cinematography seems to generate anxiety too, with the harsh lighting and sharp camera angles accentuating the drama. Nine Days in One Year commences with irradiation accident at the plant: sirens sound and warning signs flash. A voiceover alludes to real risks: ‘The events described in this film might not have actually happened. Expert in nuclear physics might even say that these events could not have occurred. Who are we to argue with them?’ Officially, Mayak was another such event that ‘might not have actually happened’ until … more than thirty years later, it was admitted to have occurred. Romm’s achievement in 1962 was not only to have made Nine Days in One Year, but also to have secured cinema distribution in the face of the concerns of Mosfilm studio bosses about its deviation from the techno-utopian line.[9]

Looking back, Yankilevsky recalled the close company that sometimes formed between artists and scientists in the Soviet Union in the 1960s. Alluding to Boris Slutsky’s famous 1959 poem (‘Physicists and Lyricists’ / ‘Fiziki i liriki’), he recalled:

Science at that time was personified with social progress: astronautics, computer science, genetics … At the same time, understanding the possibility of instant destruction of life on Earth and the involvement of scientists in this sharpened their interest in the fate of humanity and its place in the Universe, in philosophy and art … I think that at that time in Soviet society these were the two groups that most complemented each other … Artists were interested in scientific ideas that were not technological or abstractly scientific in nature, but rather philosophical and world-orientated.[10]

To some artists of Yankilevsky’s generation, scientific research offered a zone of relative intellectual freedom. The hegemony of realism from the early 1930s had extinguished fantasy in art. In the early 1960s it revived, and Soviet science, it seems, provided many of the resources for renewal. The extensive network of research centres which had formed during the Khrushchev era provided exhibition spaces for abstract art, often in the face of official disapproval. In 1965 Yankilevsky mounted a show of his paintings in the Institute of Biophysics at the USSR Academy of Sciences, which was closed by the authorities a day later. Publishing his images — as scientific illustrations — proved less controversial. Under editor Nina Fillipova from 1966 and art director Yuri Sobolev from 1967, Znanie- Sila (Knowledge Is Power), a long-standing and popular science magazine commissioned many of young artists as illustrators, most of whom were unable to secure membership of the artist’s union. Powerful visual metaphors and abstract patterns could describe new hypotheses in particle physics, genetics or astrobiology. Sobolev’s tried to steer a course between physics and metaphysics: an illustration should, he said, give ‘a concrete “earthly” coating to a scientific idea, while at the same time trying to preserve the feeling of this idea’s abstractedness and universality’.[11]

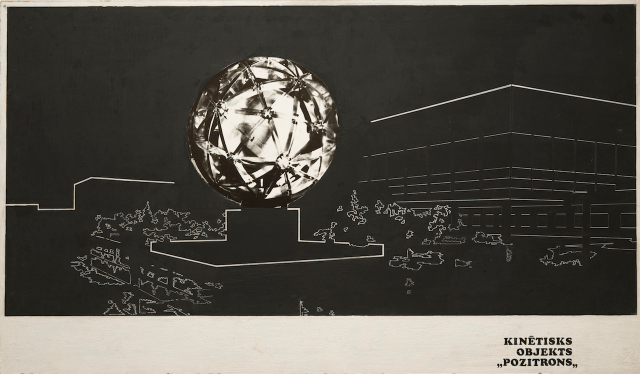

Thereafter, a new lexicon of scientific symbols — the paths of electrons around a nucleus, the pulsing line of an oscilloscope, the flashing dials of the computer console —entered into Soviet visual culture. They were often accompanied by a synecdoche for ‘scientific socialism’ — the white-coated scientist. In the 1970s this new visual imaginary appeared in public spaces as brightly-coloured mosaics or stained-glass schemes decorating schools, universities, factories and public buildings. In this way, nuclear power plants — which had once been a taboo subject — became public totems. The entire front elevation of the administrative office of the Yuzhnoukrainsk power plant in Ukraine, for instance, is ornamented with a vibrant abstract relief combining radiating lines of energy with scattering doves of peace.[12] Similarly, in the mid 1970s, Latvian artist Valdis Celms conceived his ‘Positron’, a kinetic art work for public space. Bathed in different colours to indicate work and festive days in the Soviet calendar, the massive sphere was designed to be installed in the grounds of the Ukrainian electronics concern where it would turn on its axis.[13]

The Dvizhenie (Movement) group which was formed by students of the Central School of Art in Moscow in the early 1960s shared this pervasive enthusiasm for science and technology. When exhibited in scientific institutes like the House of Culture attached to the Kurchatov Institute in Moscow in 1966, the group’s early abstract images — often exploring ‘infinite’ geometries such as the spiral — could be characterized as experiments in form, materials or perception. Dvizhenie’s chief theorist Lev Nussberg wrote: ‘The synthesis of different technical means and art forms is [an] important side of our searches. An artist must take all the basic means that exist in nature-light-color, sound, movement (not just in time and space), scents, changing temperatures, gases and liquids, optical effects, electromagnetic fields …, etc. All depends on the creative fire of the individual.’[14]

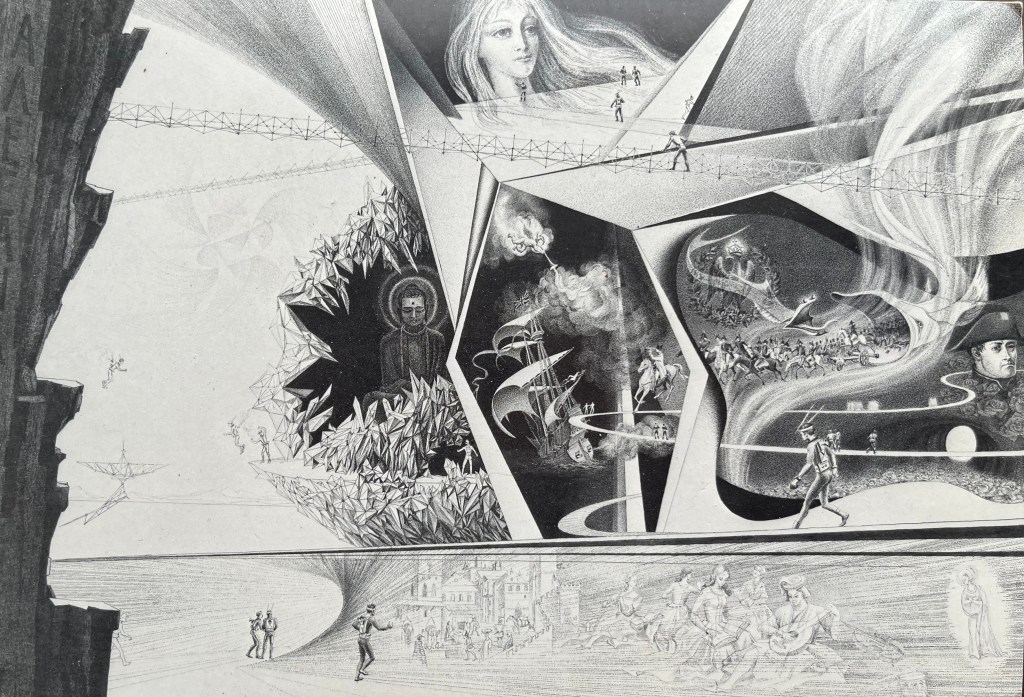

At the end of the decade, Dvizhenie conceived its most ambitious idea, the Artificial Bion-Kinetic Environment (IBKS / Istkustvennaya Bion-Kinetitscheskaya Sreda).[15] It was the guiding concept behind various installations and performances that the group created until its break-up in the 1970s. Art was no longer to be a separate category of objects but was understood in terms of interaction and environment with the aim of producing the kind of fulfilled existence that might be understood as the purpose of communism. In an extensive description of the concept penned in 1968, Nussberg, for instance, describes the experience of a boy studying the theory of relativity in the IBKS: ‘in front of him spatio-temporal objects and phenomena appear and take form that are completely natural and real (of course, they are artificially created but in the technological and scientific sense they are absolutely perfect illusions)’. According to Nussberg, the IBKS would develop in three phases: the first would be populated with architectural megastructures that owed their form to crystals, complex molecular structures or perhaps seed pods. In its second ‘cybernetic’ phase, ending circa 2070, the IBKS would expand to form a network of intelligent zones. Each created by researchers from a Central Administration and Regulation Centre, they would learn to self-correct their operations. Covering the planet, the zones would form a single ‘carpet’ into which rivers, lakes, marshes, animals, weather and other natural phenomena would be stitched, along with fantastic machines. Humans would co-exist with ‘bionkins’ (part mechanical, part organic beings) and robotic ‘cybers’. The third phase alluded to the complete integration of consciousness and environment. This involved the ’rejection of the biological basis (protein basis) of man, and a rejection of the genus of “homo sapiens” with the aim of overcoming himself. In a protracted process, man will be succeeded by a rational species … another stage of evolution, one no longer directed by bio-evolution, but by techno-evolution, and in a spiritual direction.’

Nussberg’s dizzying prognosis drew on many intellectual currents flowing through Moscow intellectual life in the 1960s, not least the ideas of Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky, the Ukrainian mineralogist and geochemist. Active before the October Revolution, Vernadsky had been one of the first scientists to recognise the importance of studying radioactivity and in 1922 became the director of the State Radium Institute newly founded in Petrograd to harness the power of atomic energy. He died in 1945 but his research laid tracks for the atomic programme in the years to come. But this is not what attracted artists: rather, it was Vernadsky’s vivid ideas about the nature of living matter on the planet and the unexplored Cosmos. Occasionally approaching mysticism, his writing issued bold challenges to conventional ideas about the natural and the artificial, and the differences between living and inert matter, seeing a continual migration of atoms from one to other and back again in the geological processes which formed our world. Vernadsky’s conception of the Biosphere is a precursor of the modern idea of the planet as an integrated living and life-supporting system. Similarly, his concept of the Noosphere seems to anticipate contemporary understandings of the Anthropocene: ‘The Noösphere is a new geological phenomenon on our planet’ he wrote. ‘In it for the first time man becomes a large-scale geological force. He can and must rebuild the province of his life by his work and thought, rebuild it radically in comparison with the past. Wider and wider creative possibilities open before him. It may be that the generation of our grandchildren will approach their blossoming.’[16] This was a belief in the power of humanity to act rationally and in the interest of the planet: ‘… the human had realized for the first time that he was a dweller of the planet and has to think and act in the new approach that is not limited by minding each individual, family or tribe, states or their alliances but in the light of the globe as a whole.’[17] Dvizhenie’s final phase of the IBKS — projected for the twenty-third century — was an explicit envisioning of the Noösphere, a conjecture that far outstripped any official forecast.

Despite its uninhibited utopianism, Dvizhenie’s IBKS project sounded a note of environmental caution too.[18] ‘Danger,’ Nussberg wrote, ‘lies in the increasing pollution of the atmosphere, water, and flora due to the rising speed of technological and industrial development, due to the thoughtless exploitation of natural resources as well as water and the atmosphere as a dumping ground … All of this, and much more, inevitably leads to the disruption of the existing balance in the biosphere of our planet. Without being fully aware of it, people tend to blame technology rather than themselves for these dangerous phenomena — although they are primarily the main culprits of this impending catastrophe.’[19] His words sound much like critiques emerging from Soviet science at the time. Famously, Soviet physicist and co-inventor of the Soviet Hydrogen Bomb, Andrei Sakharov wrote a long essay ‘Thoughts on Progress’ which was smuggled out of the country and published in full in Het Parool, an Amsterdam daily, and the New York Times in 1968, much to the dismay of the Kremlin. He warned his readers of the catastrophic effects of nuclear warfare as well as ‘the problems of dumping detergents and radioactive wastes, erosion and salinization of soils, the flooding of meadows, the cutting of forests on mountain slopes and in watersheds, the destruction of birds and other useful wildlife … caused by local, temporary, bureaucratic, and egotistical interest and sometimes simply by questions of bureaucratic prestige’.[20]

Although exceptionally brave and forthright, Sakharov was by no means alone in his views: indeed, his profession played a major role in the formation of the large and influential environmental movement which grew in the USSR in the 1970s and 1980s.[21] The relative intellectual freedom given to scientific research after the Stalin years permitted a wide diagnosis of the degradation of the natural environment. Vernadsky’s concept of the biosphere formed the conceptual ground for new research into ‘the globe as a whole’: Soviet ecologists and climate scientists undertook pioneering work into man-made climate change and, in the early 1980s, hypothesised the idea of the ‘nuclear winter’.[22] They took their arguments beyond the technocratic zone of scholarly research by issuing collective letters of protest to the media about the despoliation of ecosystems like Lake Baikal, the oldest and deepest freshwater lake in the world. In the 1970s, Znanie-Sila, the popular science magazine, published a steady stream of reports on the disturbing environmental effects of Soviet industry. Increasingly, Soviet futurology or what planners preferred to call ‘prognozirovanie’ (forecasting), acquired dark undertones.[23] Ruminating on the role of art to imagine the future, as well as his own creativity in the 1960s, Yankilevsky paraphrased the early C19th Russian philosopher, Pyotr Chaadayev: ‘There will never be enough facts to explain everything. But there are always more than enough of them to anticipate everything.’[24] Rather than forecasting the future, art could be a ‘premonition’, a word which carries associations with feelings and even foreboding. In light of events — not least the Chornobyl catastrophe in the Soviet Ukraine in 1986 — Yankilevsky’s Atomic Station, was, it seems, such a work.

[1] V. Yankilevsky, ’Memoir of the Manezh Exhibition, 1962’ Zimmerli Journal, No.1. (Fall 2003) pp 67-78.

[2] Susan Emily Reid, ‘In the Name of the People: The Manege Affair Revisited’ Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, v. 6 no. 4 (2005) 673–716.

[3] Paul R. Josephson, Red Atom Russia’s Nuclear Power Program From Stalin to Today (Pittsburgh, Penn., University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005)

[4] Nikita Khrushchev cited in K. Pisanov ‘God 1980, nauka’ in Znanie-Sila, 10 (1961)

[5] ‘Interv’yu s khudozhnikom Vladimirom Yankilevskim’ https://artinvestment.ru (19 April 2010) – accessed January 2024.

[6] Kate Browne, Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (Oxford: OUP, 2013)

[7] G. Kiarszys ‘A Nuclear Generator of Clouds: Accidents and Radioactive Contamination Identified on Declassified Satellite Photographs in the Mayak Chemical Combine, Southern Urals’ in Cambridge Archaeological Journal v.32 n.3, (2022) 409-429.

[8] Zhores Medvedev, Nuclear Disaster in the Urals (New York, W. W. Norton, 1979).

[9] Josephine Woll, Real Images: Soviet Cinema and the Thaw (London: Bloomsbury 2000) 130.

[10] Zhanna Vasilyeva, ‘Triptikh v pis’makh. Pis’ma Vladimira Yankilevskogo iz Parizha’ (January 5, 2018), https://lechaim.ru/events/yankilevsky/ accessed January 2024

[11] Yuroi Sobolev, ‘The Artist’s Role in a Popular Science Book’ in Anna Romanova and Galina Metelichenk, eds., The Islands of Yuri Sobolev (Moscow: Moscow Museum of Modern Art, 2014) 270.

[12] Yevgen Nikiforov and Polina Baitsym, Art for Architecture. Ukraine, (Berlin: Dom, 2020) 274-5.

[13] Margareta Tillberg, ‘”I will make Machines that Fly Underwater”: Electro-kinetic art/ design in Latvia in 1970-80’ in Ieva Astahovska. ed. From Johansons to Johansons: Explorations and experiments in Latvian art,(Riga: Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, 2015).

[14] Nussberg cited by Vyacheslav F. Koleychuk, ‘The Dvizheniye Group: Toward a Synthetic Kinetic Art’ inLeonardo, vol. 27, no. 5 (1994) 433-36.

[15] This description is derived from a draft manuscript that Nussberg called ‘Chapter II of a planned work, in which I will expound my ideas about the man of the future’. It appears in Lew Nussberg und die Gruppe Bewegung, Moskau 1962-1977, exhibition catalogue, Museum Bochum (1978).

[16] Vladimir I. Vernadsky, ‘The Biosphere and the Noösphere’ in American Scientist, v. 33, n. 1, (January 1945), 9.

[17] Ibid

[18] By 1978, when Nussberg had left the USSR and was based in Paris, this note of caution was issued as a full ‘alarm’ in what he called Projekt für ein kinetisches Environment ‘Mahnung’. See Lew Nussberg und die Gruppe Bewegung, Moskau 1962-1977, exhibition catalogue, Museum Bochum (1978).

[19] Ibid, TBC

[20] ‘Text of Essay by Russian Nuclear Physicist’ in New York Times (22 July 1968) 17.

[21] See Douglas R. Weiner, A Little Corner of Freedom Russian Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachev (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2002).

[22] Jonathan D Oldfield, ‘Imagining climates past, present and future: Soviet contributions to the science of anthropogenic climate change, 1953-1991’ in Journal of Historic Geography, 60 (2018) 41-51.

[23] See Eglė Rindzevičiūtė, ‘A Struggle for the Soviet Future: The Birth of Scientific Forecasting in the Soviet Union’, Slavic Review, 75, no. 1 (Spring 2016) 52-76.

[24] Yankilevsky interviewed by Vladimir Tarasov in Paris (undated), YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yv8ps0Jxbx0 – accessed January 2024.