This essay will appear in Art in Translation later this year. It is a version of a talk that I gave in Poznań in 2023 at the excellent Hot Art, Cold War conference organised by Institute of Art History, Adam Mickiewicz University.

——————

Television, film, radio and the press form the picture of today’s world (yesterday’s as well). And this is not better or worse. It is all quite simply as it is …[1]

Teresa Tyszkiewicz and Zdzisław Sosnowski, artists’ statement, 1980

In 1972 the artist couple KwieKulik—Zofia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek—began a run of photographic works that they called Ameryka, a series of self-portraits in which they were sometimes accompanied by their young son. In both staged photos and casual snapshots, they recorded scenes from their own life in the Polish People’s Republic (PRL); a walk in the park, making art in the studio, life at home, holidays. When set in columns and captioned, the photographs looked much like a photo-spread, the characteristic layout of photo-journals. Indeed, KwieKulik presented these photographs alongside copies of Ameryka, a glossy periodical published by the United States Information Agency in different language editions and distributed by American embassies across Eastern Europe in the 1960s and 1970s. Showcasing different aspects of American life, its power as Cold War propaganda lay in its capacity to present ordinary lives—scenes of family life, work and leisure—alongside exceptional achievement in culture, science and technology. KwieKulik’s casual gestures in their self-portraits seem indebted to the relaxed self-confidence exuded by Americans on the pages of Ameryka.

A scene in which the young Polish artists seem to have spotted something in the distance that had amused them while out walking is accompanied by this caption:

Zofia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek with a pram on the route of their daily stroll in the Praga Park in Warsaw (December 1972). The Park is situated between their Studio of Activities, Documentation and Propagation (PDDiU), and the Zoo. Here, they are seen enjoying a break from their everyday duties and the work on “Activities with Dobromierz”, featuring their little son Maksymilian Dobromierz. Zofia is sporting a fashionable and expansive sheepskin coat (a gift from her first husband), a garment every citizen desired. Przemysław is wearing an overcoat made of pre-war hand-woven “herringbone” homespun inherited from his grandfather. The coloured brown beret on his head was tailor-made by a hatter. [Fig. 1]

This was an image of narcissism but not necessarily of their own. It signaled the kinds of self-interest that thrive in consumer societies: namely, that bodies are something to be adorned and managed; that individuality is achieved in the consumption of products and services; that wants are construed as needs; and that the lifestyles of others can shape our own dreams and desires. Perhaps there is an element of parody at work in this image of Ameryka: Polish lifestyles in 1972 did not mirror those of their counterparts in North America. But KwieKulik’s Ameryka is not about shortage, the characterization usually attached to Eastern Bloc economies.[2] Instead, what they demonstrate is an understanding of the codes of “lifestyle” mediated through dress, gestures and actions.

Ameryka—created from 1972 onwards—is an early contribution to a cluster of Polish film and photographic works by artists, expressing a growing awareness of living with and through mass media images. In what follows I will explore these practices, as well as the intellectual and economic conditions that prompted a heightened awareness of the changing “iconosphere” (ikonosfera) of socialist Poland. This was art historian and theorist Mieczysław Porębski’s term to describe the deep penetration of print and electronic images into all aspects of human life. In his 1972 book of the same name, Porębski invited artists to turn their attention to “the vast field of mass forms and visual media” and to leave “the sacred enclaves of museums and exhibition halls in order to immerse oneself in the everyday bustling market of things and events, to be interested in everything—in games of chance and psychoanalysis, optical illusions and advertising, customs and politics, to demonstrate and provoke, to intrigue and bore, to clown and to fight”. Artists could enjoy what he called “the privilege of participation” in this burgeoning world without the weighty burden of “concepts and criteria”.[3] This is what distinguished them from the sociologists and psychologists then beginning to investigate mass communication in Poland.A number of neo-avant-garde artists from the mid 1970s appear to have accepted Porębski’s challenge: not only did they remediate mass media images circulating in advertising and on television and cinema screens, they also addressed the forms of fantasy and pleasure that these new dream worlds promised their viewers. What meanings might be attached to their art works when, increasingly, hard lines were being drawn between socialist state and the anti-communist opposition?

Commodity Aesthetics

It is noteworthy that KwieKulik called their series Ameryka. Paradoxical though it might seem, an “American lifestyle” had already been seen by some prominent voices in the PRL for more than a decade as a possible future for their compatriots. The USA supplied compelling images of material affluence and technologically-driven modernity, which were accepted, though not without question, as prospects for all modern societies, even those that declared their ideological objection to capitalism and “American imperialism”. Even the highest authorities seemed to hold this view, not least First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev at the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Moscow 1961 when he set the aim of “outstripping the more advanced capitalist countries in their standard of living”.[4] This achievement would be measured in the supply of housing, education and entertainment facilities, and consumer goods. Television was a key index of progress, not least because states across the world were in the process of establishing national television broadcasting systems. In 1963 the chairman of the Radio and Television Committee (Komitet do Spraw Radia i Telewizji) in Poland (and Minister of Culture between 1952 and 1956) Włodzimierz Sokorski declared that it is “… not only the style, but also the content of the mass culture of the capitalist world is not without new, progressive elements.”[5] He was then negotiating broadcasting rights to American programs and, soon after, Polish viewers tuned into NBC’s mawkish Western “Bonanza”.

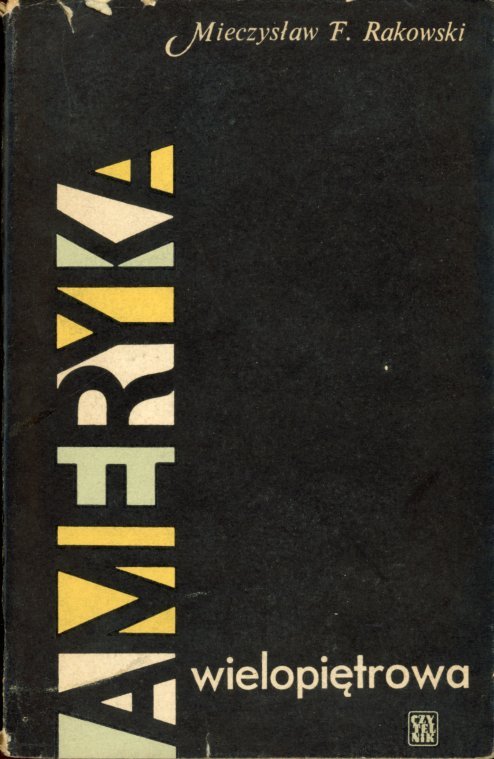

Observing this approaching horizon, Polish sociologists became particularly exercised by the likely effects of material affluence and mass media on socialist society. America was a test zone. There, the social and psychological impact of “industrial civilization” could be measured, and critiqued. A steady stream of sociological studies and journalistic reports were published in the early 1960s by Polish commentators reflecting on US society, culture and commerce. They included a number of books by authors who had first-hand experience of life in the USA as one of the 1,500 Poles who went there on scientific or cultural exchange grants between 1958-1962.[6] Clearly, sponsored travel to Poland’s Cold War enemy was rare even during this period of improved East-West relations, and Polish researchers were carefully vetted before they crossed the Atlantic. Future (and last) First Secretary, Mieczysław F. Rakowski was one of these field workers, publishing the diary of his observations of class and race (as well as his nighttime television viewing habits in motel rooms) as Multistorey America. A Travel Journal (Ameryka wielopiętrowa. Dziennik podróży) in1964. But it would be wrong to see the responses of these travelers to the USA as wholly blinkered by the certainties of ideology. The case of Jan Strzelecki is illustrative. A Ford Foundation scholar who went to the University of California in 1959, Strzelecki was a “Thaw” intellectual committed to the reform or what was sometimes called the “humanization” of socialism after the catastrophe of Stalinism. Like many other intellectuals who had pledged their loyalty to the communist project in Poland in the aftermath of the Second World War, the irrationalism and brutality of Stalinism triggered a crisis of faith. Following Stalin’s death and the succession of relatively moderate communists to power, Strzelecki was an active participant in lively and frank discussions—in person and in print—about how to restore authentic forms of socialism.[7] In American Anxieties (Niepokoje amerykańskie), the book that he wrote on his return to the PRL, he examined the ways in which materialism—in its consumerist mode—was accompanied by a breakdown of community and loss of self. Despite their affluence, why, he asked, were Americans unhappy? A key influence on his thinking was Erich Fromm’s The Sane Society (1955), in which the German thinker made a psychoanalytical diagnosis of capitalist society, declaring its major product to be social alienation.

American Anxieties passed the scrutiny of the Polish censors. In one sense this was to be expected: after all, Strzelecki’s slim volume offered a critique of life in the USA. But it also raised questions about alienation, anomie, human individuality and creativity, which could be asked of the PRL too. Indeed, this was Strzelecki’s thesis; namely that the anxieties of the age were more the product of “industrial civilization” than of Cold War ideological differences. That said, Strzelecki stressed the importance of not importing American excesses to Poland: “in our zeal to overtake, we should exercise care not to overtake them [the West] in this respect. It is therefore necessary to scrutinize the source of these anxieties in good time and not to assume that our ownership-free system automatically makes us free of them while preparing a renaissance the likes of which the world has never seen.”[8] Although not an ad hominem address to the leader in the Kremlin, these words surely referred to the bold promises of his 22nd Congress speech. What checks and benefits might socialism offer the seemingly inevitable progress of industrial civilization? Might, as one sociologist put it in 1964, the ‘elimination of commercialism’ and the ‘educational effects of cultural policy’ in Soviet-type societies produce better mass cultural products? [9]

It is notable that Strzelecki did not stiffen his critiques of American life with Soviet doctrine. Instead, he turned to America’s own critics. Some, like Fromm, were on the Left but others were conservative public intellectuals who protested the attrition of traditional patterns of life in the 1950s—white, middle class and family-oriented—by rampant commercialism. This approach was found elsewhere in Polish intellectual life. In 1970 director of the Department of Culture of the Central Committee, Jerzy Kossak, and Wiesław Gornicki, the editor of World (Świat), a photo monthly based closely on the format of Life magazine, edited an anthology of the writings of these American critics—in Polish translation—called Super Ameryka. To Kossak and Górnicki, these American intellectuals offered a deeper understanding of modern life across the Atlantic, all the more compelling to Polish readers, one suspects, than the material emanating from Institut SShA (USA Institute) established in 1967 in the USSR. Many of these home-grown critics brought a psychological or even psychoanalytical framing to their analyses of American life, albeit in the “Pop” mode favored by US essayists in the 1950s and 1960s rather than the analytical manner. Vance Packard’s dissection of the use of motivational research by advertisers and politicians in The Hidden Persuaders features; as does Philip Wylie’s essay “Common Woman”, an exercise in misogyny claiming to be a diagnosis of America’s particular Oedipal Complex. In it, American “moms” were accused of emasculating their sons and turning their daughters into obsessive consumers of luxury. Kossak and Górnicki did not detail what the precise value of Wylie’s text to Polish readers might be. But it was clear that, broadly, their interest was in the application of psychoanalytic theory, still a poorly-understood field in the PRL (a product of Soviet prohibitions[10]). Super, in the title of the book, ostensibly referred to John Bainbridge’s 1961 book The Super Americans on life in Texas (from which an extract was included), but to these Polish editors it also pointed to the superego. In psychoanalytic theory, the superego (the conventional English translation of “das über ich”) acts as a kind of moral compass or conscience guiding the self towards better actions and thoughts. The self-appointed role of the American intellectuals whose writings they anthologized was to school the id, the pleasure-seeking part of the self that is so susceptible to unruly instincts and irrational desires. This was a role that Kossak and Górnicki claimed for themselves in the PRL.

Super Ameryka was an early publication in a long-running series of small format, inexpensive books issued in large numbers by PIW (State Publishing Institute) called Library of Contemporary Thought (biblioteka mysli wspolczesnej). Philosophy, information and media theory, popular science, psychology and sociology formed its main pillars. Some of the titles were by home-grown authors (including Porębski whose Ikonosfera appeared under this imprint in 1972): others were translations of works already published in North America and Western Europe included books and essays by Marshall McLuhan, Erich Fromm, Umberto Eco, Alvin Toffler, Michel Foucault and many others. Some belonged to the tradition of “Western Marxism,” which set out to understand the effects of superstructural phenomena like culture, education on consciousness in bourgeois societies. PIW’s output formed a remarkable library and contributed significantly to Poland’s self-image as the most liberal state in the Eastern Bloc.

Second Poland

Accompanying these analyses in print of the effects of “industrial civilization” was the steady creep of commercial imagery into the PRL from the West. Hollywood films and foreign language television programs were imported to entertain Polish audiences. The most popular film at the box office in 1972, for instance, was Paramount Pictures’ Love Story (dir. Arthur Hiller, 1970).[11] Monthly magazines increasingly featured advertising and fashion spreads, sometimes borrowed from western glossies. One of the most ambitious women’s magazines of the period Ty i Ja (You and I, published 1960-73) featured fashion collections first published in Elle in Paris, alongside reports on new trends in cooking, interior design as well as new films and music from around the world. Homegrown images played their part too. Arguably, Poland underwent a deep “Americanization” from below in the keen embrace of pop music and fashion by the young from the end of the 1960s onwards. And to channel these desires, the authorities created fashion houses and boutiques, and state-recording companies issued rock albums.[12] These tendencies accelerated after 1970, when a new regime under First Party Secretary Edward Gierek had come to power following rioting over shortages and price hikes in 1970, promising to restore the ambitions of socialism and address the material needs of society. In May 1972 Gierek announced a spectacular program of industrial expansion, along with bold communication and urban projects: “It’s a great matter—building a second Poland within the span of one generation—a more prosperous Poland, one that meets the aspirations of the citizens of a modern industrial country” he declared.[13] Poland mortgaged itself to the West in the expectation that it would become an industrial power selling its own products to the world. By signing contracts with Western corporations to acquire manufacturing rights and new manufacturing technologies, the country would make a dramatic leap into the future, and its citizens would reap the rewards.

Advertising had already been recognized as a necessary feature of socialist economic management during the period of destalinization in the late 1950s. A national advertising agency, “Reklama” Advertising Service Company (Przedsiębiorstwo Usług Reklamowych “Reklama”), had been created in 1956 to manage desires in the planned economy, and the “Agpol” Foreign Trade Company (Przedsiębiorstwo Handlu Zagranicznego “Agpol”), was established in 1959 to promote Polish exports abroad. Experts debated how to promote goods and services without promoting venal desires or wasteful luxury, and declared that the purpose of socialist advertising was not to sell things but to produce expert, well informed consumers. This, they characterized as “rational consumption”, a kind of delibidinized form of promotion in which need was carefully regulated. This discourse continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s with weighty handbooks published like Advertising. Its Organisation and Function in Socialist Economies (Reklama. organizacja i funkcjonowanie w gospodarce socjalistycznej, 1976), which set the terms for new fields such as television advertising, established the ideal formation of expert advertising “cadres”, and outlined statistical methods for assessing the efficacy of advertising.[14] But on the evidence of the promotional images commissioned by Reklama and Agpol, the guide rails of “socialist advertising” had been removed by the mid 1970s (if they had ever been in place), and the results looked largely indistinguishable from the products of ad agencies in Western Europe. Polish creatives—often artists commissioned by Agpol—were highly proficient encryptors of the codes of consumerism, creating seductive promotional campaigns for Lot, the national airline, and luxury goods for export like perfumes. The forms of reification which assigned agency to things and treated human beings as mannequins were just as evident in domestic advertisements for beauty products or cars. Under Gierek, it became clear that, increasingly, Poles were being addressed as consumers rather than as productive workers or as comrades. “Bourgeois” aspirations—to own, to be fashionable, to be entertained, to have leisure—were legitimate ambitions. Gierek’s 1972 slogan “Second Poland” pointed, unintentionally, to the phantasmagoric aspect of a “new” Poland made in the image of Western modernity. The fact that there was a significant gap between the availability of images and of things, of commodities, is another matter.

So what was the response of artists to this intensification of commodity aesthetics in Poland under Gierek? The best known is Natalia LL’s Sztuka Konsumpcyjna (Consumer Art, 1972-75), a series of photographs and short films in which models, sometimes topless, lick, play and, eventually eat different foods. Bananas, breadsticks and sausages are treated like phalluses; whilst jelly and cream perhaps suggest body fluids. Sexualizing food and emphasizing orality, they offered a provocative commentary about the elision of desire and need. In this art, the act of consuming is carnal and fleshy, perhaps overly so.[15] Similarly, Zygmunt Rytka, a young photographer, addressed symbols of socialist consumerism of the day, not least the Polski Fiat 126p, the car made in partnership with the Italian automobile company from 1973 and dubbed the “Maluch.”

© Contemporary Art Foundation In Situ

It was launched to satisfy the deep desire for car ownership at the time. In 1976, Rytka took a series of photographs and made a short film of a young woman getting in and out of the car. Over and again, she slips into the passenger seat in a mini skirt. Her legs hold the attention of the camera in the manner of much eroticized advertising in the West. Other shots focus on the male driver’s hand on the gearstick, a gesture which connects, by means of crude symbolism, automotive and sexual drives. Rytka demonstrated his fluent understanding of the language of commodity aesthetics. What makes his Fiat 126p photographs and film seem truly perverse is that the object of desire—the car—needed no advertising in the Polish People’s Republic, such was the pent–up demand to own one. But, of course, what was being “sold” to Poles at the time was the narcissism of consumer culture; that a body is something that can be used to market goods and services, and can be an object of consumption in its own right.

Poland’s “Pictures Generation”

Natalia LL and Rytka were not the only artists concerned with the changing iconosphere of socialist modernity. Both belonged to an emerging generation that Łukasz Ronduda describes as appropriating the commodified image in his pioneering book on Polish art in the 1970s.[16] One of Rytka’s allies was Zdzisław Sosnowski, an artist and curator at Warsaw’s Współczesna Gallery (with Janusz Haka and Jacek Drabik) between 1975 and 1977 and then in nearby Studio Gallery until 1981. Sosnowski’s best-known work was a number of short films and photos with the shared English title Goalkeeper (1974-75). In one, Sosnowski, guarding the goalposts, repeatedly dives for a football whilst dressed in a white suit, black sunglasses and smoking a cigar, the symbolic garb of a “star”. The absurd action shifts from empty football pitch to interior whilst the soundtrack of cheering fans continues without interruption. It then transforms into a sexual encounter. All the while he holds tight to a football: after all, this is what his celebrity depends on. In a closely-related gesture, he had photographs of himself as a goalkeeper appear in the sports press. At the same time, he arranged for interviews with himself as goalie to appear in exhibition catalogs and the art press. In this way, he eschewed the divisions between the lofty asceticism of the art world and the sentiment of popular culture.[17] After the relative success of the Polish football team and, in particular, the heroism of goalkeeper Jan Tomaszewski in the 1974 World Cup in West Germany, no other theme could have been as popular or, for that matter, populist. Goalkeeper projected Sosnowski’s interest in the psychological and social appeal of celebrity, a key category of mass media image production:”I am a goalkeeper. I prepare information about this in the form of numerous photographs, films, video tapes or publications in high-circulation sports magazines from the source material, which consists of registrations of certain imitations of reality or characteristic points in the course of a phenomenon known to us all, such as a football match, training or the life of an athlete off the pitch, etc.”[18]

In creative partnership with Tyszkiewicz, Sosnowski also made a series of films which explored the fetishistic desires triggered by fashionable commodities such as Permanent Position (Stałe zajęcie, 1979) and The Other Side, (Druga strona, 1980) that I will discuss in more detail below. Tyszkiewicz worked independently too as an artist filmmaker: her short films Grain (Ziarno, 1980) and Breath (Oddech, 1981) explore the haptic effects triggered by images.[19] Other artists—more recently rediscovered by art historians—include Jadwiga Singer in Katowice who, along with her colleagues in the Laboratory of Presentation Techniques explored the sexualized languages of advertising in print and on screen.[20] In Warsaw, Teresa Gierzyńska made a series of art works from 1973 onwards that carried the grandiloquent title, The Essence of Things (Istota rzeczy). She transferred images from West German magazines of the kinds of fashionable, beautiful people that only exist as images on thick paper using a chemical agent. The knowing paradox of this title was that the resulting collages featured images of humans as things, i.e., reified, stripped of any metaphysical associations like the idea of essence.[21]

Viewed together, these Polish art works from the 1970s form strong parallels with the output of the so-called “Pictures Generation” that emerged in the USA at the same time. Given their name from a 1977 exhibition in Artist’s Space in New York, this loose network of artists set out to examine mass media images. Artists working typically in photography, film and video, like Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince, have been widely credited with mounting a critique of the shibboleths of modern art, namely the ideas of originality and self-expression by embracing the imagery of advertising and cinema.[22] As many commentators have noted, they were particularly interested in how desire functions. And yet they displayed a dispassionate approach to objects of their desire, sometimes engaging in “mechanical” acts of reproduction. That these two groups of artists on different sides of the Cold War divide were unaware of each other’s art is almost certain: what is less obvious but no less true is that they shared few common points of intellectual reference either. For the Pictures Generation and, perhaps more evidently, the curators and critics who interpreted their art, considerable intellectual buttressing was to be found in Guy Debord’s arguments in La Société du spectacle, Walter Benjamin’s conception of the “aura” as well as Roland Barthes’ 1967 declaration of “La Mort de l’auteur” and Jean Baudrillard’s Pour une critique de l’économie politique du signe (1972). For some early analyses of Sherman’s ‘Untitled Film Stills’, feminist theories of the image were also important.[23] Little of this intellectual apparatus was available in the PRL at the time and, with the exception of Benjamin,[24] most of these neo-Marxist theorists were absent from the critical discourses concerning visual culture.[25] For instance, the art critic Jerzy Busza wrote a substantial analysis of Sosnowski’s Goalkeeper series at the start of the 1980s. His conclusions were similar to the image-analyses being developed by artists across the Atlantic, as this passage illustrates:

Sosnowski, solely for the purpose of art, meticulously repeats the operational maneuvers of mass culture strategists, more specifically, the advertising that promotes the sports champion. He depicts the mythologization of the reality of the stadium hero, all the more pointedly because it is a false and non-existent reality. In doing so, he provides us with a key to the proper evaluation of such areas of public life that are mythologized by advertising.[26]

Rather than following the currents of Western Marxism and post-structuralism, Busza’s chief guides were works of North American sociology and media theory (most notably, the writings of McLuhan) that had been translated into Polish and published in recent years, some in PIW’s Library of Contemporary Thought.[27]

If the intellectual trajectories of the Polish and American artists and their champions were very different: both were responding, nonetheless, to the same phenomenon, namely, the centrality of the mass media image in life.

The Other Side

In 1980, Sosnowski and Tyszkiewicz made a short film with the title The Other Side (Druga strona, 1980). Shot from overhead, Tyszkiewicz flicks through an issue of Mode Avantgarde, a large-format and glossy portfolio of fashion images published at the time by photographer Gunnar Larsen in Paris. Rejecting what was sometimes called “the natural look” of the early 1970s as démodé, and embracing the taste for oversaturated colors and exaggerated silhouettes that marked fashion at the time, his magazine was like a primer for the production and performance of glamor in The Other Side: Tyszkiewicz dresses and undresses in sheer tights, glossy black stilettos, leopard-pattern shorts and a sparkling bikini top, while glittering make-up on her face catches the light. Her mood is self-absorbed as she caresses her legs or dances to a version of “Memphis Tennessee” by The Faces playing on a portable television in the background. Later, she appears to tease her naked male partner, her high heels threatening, sadistically, to dig into his bare feet. Catching the light of the hand-held lamp tracking her movements, silky sheets and bright-red plastic furniture create a colorful backdrop for this world of heightened sensation. Many of the same themes appear in Day after Day (Dzień po dniu) in which Tyszkiewicz seems to desire the inanimate objects with a passion. Dressed in a red slip and vertiginous heels, she seems compelled by some kind of strange drive to grasp and stroke the chic furnishings, to mount the pipes running up the walls of the apartment, and to bathe naked in the warmth emanating from a bright red lamp. Fig 4 As if illustrating the psychoanalytic concept of the fetish, Tyszkiewicz seems aroused by things instead of the “proper” sexual object, the phallus.

One of the distinguishing features of Tyszkiewicz’s film work—her own and those made with Sosnowski—is her unabashed engagement with sexuality. This was a preoccupation of most of the Polish artists who feature in this essay. Here it is important to note that the so-called “Sexual Revolution” that occurred in Western Europe at the end of the 1960s reached the PRL in the 1970s and then only faintly and within limits set by the censors. Feature film directors treated female nudity and sex scenes as steps in the progress of liberalism; “pin ups” were a regular feature of the back page of Kino (Cinema) magazine; and the “Venus” photographic exhibitions mounted in Kraków from the beginning of the decade drew large audiences to “artistic” representations of the nude from around the world. Licensed permissiveness of these kinds, were, as Karol Jachymek has argued, aligned to the regime’s program of “modernization” (which depended on borrowing from the West, literally and figuratively).[28] Put simply, the objectification of women was taken as an index of progress. Other public representations of sexuality—including LGBTQ+ themes and pornography—remained subject to what was called “socialist morality”, a censorious view of life that had been laid down in the early years of communist rule.[29] Even the sexologists whose books on sexual technique and health have been much celebrated as contributions to public understanding, found that their illustrations were censored by officials who sniffed out pornography on their pages.[30] Although pornography was inadequately defined in Polish law (as elsewhere),[31] an accusation was enough to ensure that an exhibition was closed or a publication pulped. Sosnowski experienced this at first hand when 2,000 copies of Polish Art Copyright, a catalog surveying contemporary art published by the Współczesna Gallery in Warsaw was pulped in 1975 on grounds of pornography.[32]

What are we to make of this engagement with fetishistic modes of fashion and commodity aesthetics from the West? Might Sosnowski and Tyszkiewicz’s films be understood as some kind of diary of intimate desires and dreams that were hard and perhaps even impossible to realize in the PRL? Or might these scenes be understood as something like images in a private cargo cult, an attempt to bring Paris closer by making copies of its idols? After all, the shiny, bright colored commodities and fashions which feature in The Other Side were in short supply in Poland in 1980. Neither explanation seems entirely convincing.

TVP

The television was always on in this new media art, or so it seems. Sosnowski and Tyszkiewicz have a portable playing in the background of her languid dancing in The Other Side; and Rytka set up a camera to record what was “on the box”, taking more that 5,000 still images of TV broadcasts in Photovision series (Fotowizja, c. 1978–88).[33] They were not the only keen viewers. Although broadcast television was not new (it had been launched in Poland in the early 1950s), it only came to occupy a central place in national culture during Gierek’s rule. By the end of the 1970s, 90% of Poles had a TV set and spent an average of two hours a day watching it.[34] Unsurprisingly, Telewizja Polska, the state broadcaster, was in lockstep with the communist authorities, and not simply because it performed an important propaganda role. Color television (using the French SECAM system), a new second channel (TVP2) delivering culture and entertainment, and the licensing of content from Western makers were “evidence” that the Poles were already beneficiaries of Gierek’s modernization. Watching The Muppet Show or the British sci-fi drama Space 1999 on a “Rubin” color program TV set might, in these terms, be taken as a sign of socialist progress. For critics of the regime, it might be better understood as a sedative: Stefan Kisielewski, wrote in his diary (11 February 1977), “Maciej Szczepański [the ruthless director of the Television and Radio Committee -DC] … supplies a lot of American movies, better and better entertainment and sports programs, and all of Poland is sitting in front of the TV all the time … And so Poland sleeps—and they rule.”[35] The pinnacle of televisual modernity in the Gierek years was probably Studio 2, an evening–long program transmitted once a month from 1974. The magazine–format drew large audiences for its charismatic presenters, energetic news reports, and imported feature films and TV series. Studio 2’s greatest coup was to persuade the Swedish superstars ABBA to perform at the Warsaw studios of Telewizja Polska in November 1976. The making of the program itself – including ABBA’s easygoing exchanges with Polish journalists on the flight to Poland and their journey downtown, as well as the sparkling scenography, and the operations of the television studio – occupied a significant part of the broadcast. Television spectacularized itself.

Working in partnership with the critic, writer and artist Jacek Drabik, Rytka mounted a series of exhibitions to measure the social reverberations of broadcast television including TV/Studio 2 – Rembrandt 78 in Warsaw’s Interpress Gallery in 1978; Boney M in Warsaw’s Gallery of Contemporary Art in 1979; Television = Woman (Telewizja = Kobieta) in Galeria Studio in Warsaw in 1980, and Telewizja – superprint (with Sosnowski and Tyszkiewicz) at the Artists’ Union Gallery in Kraków in 1980. Such exhibitions and artists’ films presented themselves as a form of systematic image analysis:

Today, television is the ruler of mass communication. Its social significance lies in its universality, method of transmission and full set of functions. At the same time, reflection on the phenomenon of television is still based on imperfect forms of research.[36]

These exhibitions were attempts to record and understand the phenomenon of television, rather than to criticize its content or denounce its effects. Rytka and Drabik’s fascination with the medium is evident in the November 1978 exhibition, TV/Studio 2 – Rembrandt 78, that featured more than fifty blow-up photographs of an episode of Studio 2 that had been transmitted on a Saturday evening in October. Already acknowledged as the most spectacular and successful product of Telewizja Polska, Studio 2 achieved large viewing figures. Organized like a mosaic on the gallery walls, Rytka’s video stills stressed the visual miscellany that had been transmitted into Polish homes a few weeks earlier: talking heads: the hands of concert musicians in black–tie; scenes from movies (that evening, Aleksander Ford’s Knights of the Teutonic Order had been screened): imported television shows (Space 1999); and television channel branding. Polemicizing with their colleagues in the Polish art world, they declared the redundancy of traditional artistic media: “In 1978, Rembrandt would probably be working in TV”.[37]

At the opening of the exhibition, Drabik and Rytka staged what seems to have been a scripted conversation for the cameras of Pegasus (Pegaz), a weekly cultural review on Telewizja Polska about the social significance of television. But the “real” critics were doubtful: one reviewer in Warsaw Life (Życie Warszawy) asked whether exhibiting video stills—or what Rytka called “duplicate records”—could really answer the questions raised about the distinct nature of the televisual image or the experience of viewing.[38] After all, what distinguished broadcast television was its relentless flow, each image washing over that which had preceded it.

The Carnival

Rytka’s attitude to broadcast television, like that of his compatriots, began to change at the end of Gierek’s rule, during what was dubbed the “Carnival of Solidarity” (Karnawał Solidarności)—15 months of protests and concessions that ended abruptly and violently with the imposition of martial law by the communist authorities in December 1981. From its origins as a labor union on the Baltic coast, the Independent Self-governing Trade Union “Solidarity” (Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy “Solidarność”) grew rapidly into a national organization pressing for reforms in all areas of life. During the “Carnival” democratization moved in fits and starts as the opposition secured its demands by means of strikes, boycotts and protest marches. At the same time, the economy, already failing, fell off a cliff, raising real fears of blackouts and hunger. Military exercises on Poland’s borders stirred deep anxieties about the prospect of an invasion by the Red Army like those that had rolled through Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. In December 1981. But Polish tanks—not Red Army artillery—appeared on the streets of Polish cities and Solidarity activists were interned in Polish prisons. Television changed considerably too: no one was “sleeping” in front of the small screen anymore.

All of this is evident in Rytka’s Retransmission (Retransmisja, 1988), a 15–minute compilation of footage of Telewizja Polska broadcasts between 1978 and 1983. Organized as an inexact timeline of events, Retransmission has a number of phases. In the first, the fast rhythm and abrupt cuts of Rytka’s editing accelerate time. Without pause for reflection or even comprehension, much of the imagery is, nevertheless, familiar. Iconic images from around the world flash and flicker: Elvis crooning on stage; the weather map; Ayatollah Khomeini speaking in Iran; the launch of NASA’s Challenger space shuttle; the weather map, again; grainy historical footage of Second World War battles; catwalk fashion shows; football matches; the animated title sequences of foreign and home-grown movies; news reports and talking heads. Throughout this phase, the audio, taken from broadcast footage, is unintelligible, sounding much like the hiss and broken speech of radio interference. This frenetic pace suddenly abates: longer cuts and audible voices make it clear that the pointer on the timeline has moved on to the period of conflict between the opposition and the state: the strikes of the summer of 1980; reports of the February 1981 meeting of the Solidarity trade union leader Lech Wałęsa and Deputy Prime Minister Mieczysław Rakowski; news anchors dressed in military uniforms and then footage of troops on the streets when martial law was declared in December. Perhaps suggesting the confusion and tension of the months that followed, the footage thereafter becomes frenetic and unstable and the image splits with sports footage or variety shows overlaying grim–faced news reporters. The steady flow of television pictures is broken. At one point, pornography fills the screen. Rytka cut in “found texts” from state broadcasts (including Days of Hope, Days of Drama (Dni nadziei, dni dramatu), a pro–regime documentary broadcast during martial law to defend the state’s actions) and the headlines of newspapers. Using a vision mixer, Rytka also overlaid the word “ocenzurowano” (censored) in the characteristic daubed lettering of Solidarity on the screen; first over electronic “noise”, and later over images of the ailing Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in Moscow. Censorship, a power that belonged to the state, was turned into the punchline of a bitter joke.

Unlike the dispassionate analysis of television that had been offered by Rytka and Drabik in their TV/Studio 2 – Rembrandt 78 exhibition, Retransmission, which was completed in 1988, is agitated and emotional. The basic method is much the same: a camera is pointed at a TV screen. But now the jarring pairings, the syncopation of the cuts and the hallucinogenic doubling of broadcast footage form an indictment of the role of the media in Poland. This shift from dispassionate analysis to political critique was found in the practice of other artists discussed here. As Tyszkiewicz and Sosnowski had made clear in the words which appear as the epigraph to this essay, they had once accepted “today’s world … as it is”. This was an acceptance of the inevitable progress of technology. Keen students of McLuhan, they accepted that “the medium is the message”. But the events of 1980—81 had a critical impact on them too. This is evident in Sosnowski’s Satisfaction (1980) and Tyszkiewicz’s Image and Games (Obraz i gry, 1981). Both short films deploy the techniques and themes that the couple had previously developed, including close-to-body camera work and terse editing, and red accents in what is otherwise a drab world. In “Satisfaction” the camera turns on the television screen, capturing its stuttering and flickering monochrome news imagery from Pinochet’s Chile and China after Mao’s death, before hovering over the body of a woman—Tyszkiewicz herself—dressed in alluring underwear. The camera lingers on her hips and legs. In a third scene, both she and television are studiously ignored by a man—Sosnowski himself—eating raw potatoes with a broken fork at a table covered in a red tablecloth. Even when man and woman finally interact, their relations are disconnected. A short clip, cut into the end of the film, presented an image of a crowd swelling a street in Gdansk, all distracted by some unseen event: a demonstration? A rally? Or perhaps a queue? Accompanied by the Rolling Stones song which gave the work its title, the short film offered an allegorical reading of life in the PRL in Gierek’s last year of rule. The promises of a Second Poland had withered and all that remained was unsatisfied desires. Similarly, Tyszkiewicz’s Image and Games addresses the material impoverishment of Polish society. When red—the color of glamor in other works—fills the screen, it now flags ideology, an impression which is consolidated when it forms the backdrop for a meager slice of bread. If this image is metaphoric, other elements of Image and Games approach events far more directly. A newspaper which appears on screen is the first issue of Solidarity Weekly (Tygodnik Solidarność), the most important opposition newspaper published from April 1981 until the imposition of martial law in December. It is accompanied by the singing of The Oath (Rota), a patriotic anthem, the lyrics of which had been written as a protest against German rule of Western Poland before the First World War. The film concludes with a long and steady image of Tyszkiewicz kneeling to support a bag of grain after a long struggle to put it in place. Tyszkiewicz had become, as other commentators have noted, “Mother Poland” “Matka Polka”, a highly sentimentalized icon of the Romantic imagination in the nineteenth century.[39]

When compared to her other works and those made with Sosnowski, Image and Games is a disappointing film, perhaps because of its highly conventional symbols. It lacks the unreason, irrationality and absurdity that characterized many of the films and photos discussed above: recall the Goalkeeper who never lets go of the ball, even in the bedroom; or the young woman who steps into the Polski Fiat 126p over and over again. This change of tone was no doubt a reflection of the pressures of the era: the rapid advance of anti-communist opposition and the crises that ensued required that artists take a stand. What is so striking about much of the art made before the historic watershed of 1980-81 is both its ambivalence and absurdity. Responding to the Gierek modernization project, artists like Sosnowski were both fascinated by and critical of the mass media and consumer imagery that now filled their world. This ambivalence predates Gierek and can be tracked back to the late 1950s: it was surely experienced by those Polish intellectuals who journeyed around the States like Strzelecki and Rakowski. They were equally fascinated and troubled by the spectacle of American life. The absurdity of this phase of Polish art is just as important as its ambivalence. Unlike the new sociological analyses of the media that were also appearing, it was not cool, objective or dispassionate. Sosnowski’s works displayed what Busza called the “mad freedom of creativity” (“szaleńcza wolność tworzenia”), uninhibited by the obligation to explain.[40] Instead the camera could be deployed to explore worlds of sensation and affect, desire and feeling. It could record compulsive behaviors and instinctive drives, undisciplined by reason, ideology or the superego. Deeply subjective in character, this art responded by exaggerating the already excessive fantasies and codes of the mass media and of advertising.

[1] Teresa Tyszkiewicz and Zdzisław Sosnowski, artists’ statement in Kontakt. Od Kontemplacji do agitacji exhibition catalogue(Kraków: Pałac Sztuki, 1980) np. – author’s emphasis.

[2] János Kornai, Economics of Shortage, Vol. A-B. (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1980), 25-29.

[3] Mieczysław Porębski, Ikonosfera (Warsaw: PIW, 1972) 286.

[4] “Report of the Central Committee of the CPSU to the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union delivered by N. S. Khrushchev (October 17, 1961)” in Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), Documents of the 22nd Congress of the CPSU. Vol. 1 (New York: Crosscurrents Press, 1963), 114.

[5] W. Sokorski, “Kultura Masowa i galileusz” Przegląd Kulturalny, nr 2, 1963 cited by Wojciech Włodarczyk, “Postulat społecznej historii (projektowania) rzeczy,” (June 15, 2018) – online https://magazynszum.pl/ (accessed August 2024).

[6] See Emilia Wilde, “America as Seen by Polish Exchange Scholars,” The Public Opinion Quarterly, v. 28, n. 2 (summer, 1964): 243-256. See also Jarosław Kilias, “Not Only Scholarships: The Ford Foundation, Its Material Support, and the Rise of Social Research in Poland”. Serendipities. Journal for the Sociology and History of the Social Sciences, vol. 5, no. 1-2, (July 2021): 33-45.

[7] See Magdalena Grochowska, Strzelecki. Śladem nadziei (Warsaw: Świat Książki, 2014).

[8]Jan Strzelecki, Niepokoje amerykańskie (Warsaw: PIW,1962), 114.

[9] Antonima Kłoskowska, “Mass Culture in Poland,” The Polish Sociological Bulletin, nr 2, (1964): 110-11.

[10] The history of psychoanalysis in Poland is surveyed in Ewa Kobylińska-Dehe Katarzyna Prot-Klinger, eds., Jak Feniks z popiołów? O odradzaniu się psychoanalizy w powojennej i dzisiejszej Polsce (Kraków: Universitas, 2021). In his contribution to this volume, “Psychoanaliza w polskiej filozofii i humanistyce w czasach późnego PRL-u i po solidarnościowym przełomie”, Paweł Dybel argues that it was typically represented as a historical phenomenon of the early C20th rather than a current concern until the 1980s when there was a revival of interest in both therapeutic practice and cultural analysis marked by the publication of Zofia Rosińska, Psychoanalityczne myślenie o sztuce (Warsaw: PWN, 1985).

[11] Stanisław Janicki, Film polski od A do Z (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1977), 152.

[12] See Anna Pelka, Teksas-land. Moda młodzieżowa w PRL (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Trio, 2007)

[13] Gierek speaking at the 5th plenum of Central Committee of the PZPR (May 11, 1972) cited in Marcin Zaremba, Wielkie rozczarowanie. Geneza rewolucji Solidarności (Kraków: Znak, 2023) my emphasis.

[14] Marian Strużycki, ed., Reklama. organizacja i funkcjonowanie w gospodarce socjalistycznej (Warsaw: PWE, 1976).

[15] See my “Consumer Art and Other Commodity Aesthetics in Eastern Europe under Communist Rule” in Agata Jakubowska, ed. Natalia LL. Consumer Art and Beyond(Warsaw: Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art 2017) 129-144.

[16] Łukasz Ronduda, Polish Art of the 70s (Jelenia Góra/ Warsaw: Polski Western / Center for Contemporary Art, 2009), 320-339.

[17] See Łukasz Ronduda, “Zdisław Sosnowski – instrumental usage,” Piktogram 4 (2006): 49.

[18] Sosnowski cited by J. Busza, “Bramkarz Sosnowski w reprezentacji (lepszej) reszty świata,” J. Busza, Wobec fotografii, (Warsaw 1983) 140-142.

[19] This argument is developed in my “Nieznane przyjemności. Filmy 16 mm” in Zofia Machnicka, ed., Teresa Tyszkiewicz. Ciało moje jest (Gdańsk: Słowo/Obraz terytoria, 2024) 67-99.

[20] For new research on Jadwiga Singer, see the excellent Forgotten Heritage website https://www.forgottenheritage.eu/artists/168/jadwiga-singer (accessed August 2024).

[21] See O niej. Teresa Gierzyńska (Warsaw: Zachęta – Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, 2021)

[22] See Douglas Eklund, The Pictures Generation, 1974-1984 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009).

[23] Laura Mulvey, “A Phantasmagoria of the Female Body,” New Left Review, 1/188 (July/Aug 1991): 137-50.

[24] Hubert Orłowski had edited an anthology of the German writer’s texts including “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit” under the title Twórca jako wytwórca (Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 1975).

[25] As many art historians have noted, feminist discourse was, for instance, nascent in the PRL at the time. See Agata Jakubowska “The Circulation of Feminist Ideas in Communist Poland” in Globalizing East European Art Histories, eds.Beáta Hock, Anu Allas (NY: Routledge, 2018), 135-148.

[26]J. Busza, “Bramkarz Sosnowski w reprezentacji (lepszej) reszty świata,” J. Busza, Wobec fotografii (Warsaw: COMuK 1983) 142.

[27] In his article, Busza cites recent Polish translations of Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964); sociologist Herbert Schiller’s investigations into the overweening influence of corporations The Mind Managers (Boston, MA: Beacon, 1972); anthropologist Edward T Hall’s study of the impact of space on social relations, The Hidden Dimension (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1969). He also invoked Susan Sontag’s On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), a chapter of which had been excerpted and translated in Kino magazine in April 1981.

[28] Karol Jachymek, “Seks w kinie polskim okresu PRL” Pleograf. Kwartalnik Akademii Polskiego Filmu, nr 1/2018 – online https://akademiapolskiegofilmu.pl/ – (accessed Aug 2024).

[29] Stanisław Jankowiak “Zaszczepić zasady socjalistycznej moralności,” Biuletyn IPN 10 (2001): 31-36.

[30] Renata Ingbrant, “Michalina Wisłocka’s ‘The Art of Loving and the Legacy of Polish Sexology’,” Sexuality & Culture 24, (2020): 371–388.

[31] See Paweł Leszkowicz, “Seks i subwersja w sztuce PRL-u,” Ikonotheka 20 (2007): 51-85.

[32] Ronduda, Art of the 70s, 336.

[33] This section contains ideas which are developed in my essay “Rytka on TV” in Daniel Muzyczuk, Karol Hordziej, eds., Zygmunt Rytka: Stones, Ants, and Television. Photographic Works 1971–2010 (Berlin: Spector Books, 2024).

[34] Alicja Kisielewska “Oglądanie telewizji a kultura czasu wolnego w Polsce. W poszukiwaniu przyjemności” in Alicja Kisielewska, Andrzej Kisielewski, Monika Kostaszuk–Romanowska, eds., Przyszłość kultury: od diagnozy do prognozy (Białystok: Prymat 2017), 176.

[35] Stefan Kisielewski Dzienniki (Warsaw: Wyd. Iskry, 1996), 900.

[36] Cited by Bogdan Słowikowski, “Rembrandt pracownikiem telewizji,” Życie Warszawy, 271(15 November 1978): np. Available at the Rytka archive – https://zygmuntrytka.pl/archiwum – accessed August 2023.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Dagmara Rode, “Women’s Experimental Filmmaking in Poland in the 1970s and Early 1980s,” Baltic Screen Media Review 1, vol. 3 (November 2015): 30-43.

See also Elżbieta Ostrowska, “Filmic Representations of the ‘Polish Mother’ in Post-Second World War Polish Cinema,” European Journal of Women’s Studies 3–4 (November 1998): 419–35.

[40] Busza, “Bramkarz Sosnowski,” 138